Huntington’s massive floodwall has protected the city for nearly 75 years.

By James E. Casto

HQ 76 | WINTER 2011

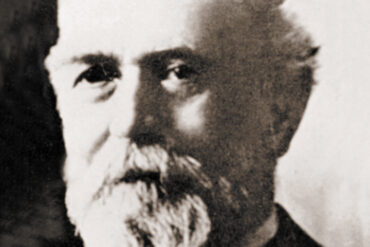

When rail tycoon Collis P. Huntington picked the site for the town that today carries his name, he was looking for a good spot to transfer passengers and cargo between his Chesapeake & Ohio Railway trains and the steamboats that then traveled the Ohio River.

Huntington chose well, and his new town thrived. But like other Ohio River communities, the young Huntington was regularly visited by damaging floods. Every few years, the Ohio would surge out of its banks and inundate the growing town. When the water receded, folks would roll up their sleeves, clean up the mess and get back to work. But nobody living in Huntington or elsewhere in the Ohio Valley was prepared for what happened 75 years ago, in the year 1937. January of that year was unusually warm. Winter’s rapidly melting snow cover combined with 19 straight days of heavy rain to create just the right conditions for flooding along the Ohio’s entire 981-mile length from Pittsburgh, Pa., to Cairo, Ill., where the Ohio meets the Mississippi.

The resulting flood, the Ohio River’s worst ever, inundated thousands of homes, businesses, factories and farms in a half-dozen states. It drove a million people from their homes, claimed nearly 400 lives and recorded $500 million in damages. Taking inflation into account, that figure would translate into more than $7 billion today.

At 11 a.m. on Jan. 27, 1937, the Ohio reached a depth of 69.45 feet at Huntington. That was more than 19 feet above the official flood stage and three feet higher than the previous record high, set in 1913. The raging water flooded most of downtown Huntington and drove thousands of residents from their homes. People in rowboats made their way along Fourth Avenue. Relief centers, set up in undamaged churches and schools, struggled to feed as many as 9,000 people a day. When the river receded, five people were dead and the city was a soggy ruin.

Could a new flood as damaging as 1937’s strike the Ohio Valley again? Experts say it’s unlikely but not impossible. If that happened, however, Huntington would be safe and dry behind the massive floodwall that has protected it for nearly 75 years.

The Huntington District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which built the floodwall in the wake of the ’37 flood, estimates that the wall has prevented $238.8 million in flood damages to Huntington homes and businesses since its completion in 1943.

But what if the floodwall had never been built? History shows that if it had not been for the efforts of the Huntington Chamber of Commerce and its president, Col. Joseph H. Long, the Huntington floodwall might not have been built. The Chamber waged a determined fight to get the wall built, an effort that even included a legal challenge that went all the way to the West Virginia Supreme Court.

Dr. W.S. Rosenheim, the Chamber’s managing director, and Long, publisher of the Huntington Advertiser and president of the Huntington Publishing Co., worked tirelessly to see the floodwall built. On Feb. 18, 1937, even as the waters of that year’s record-setting flood were still receding, Long appointed a Chamber committee to study construction of a floodwall.

The following June 15, the two men, along with City Engineer John S. Gillespie, traveled to Washington, D.C., to urge congressional action on flood protection for Huntington and other communities along the Ohio.

Testifying before the House Committee on Flood Control, Chief of Engineers Edward Markham used photographs of the flood at Huntington to illustrate the need for flood protection. He told the committee that Huntington had been flooded 23 times in 55 years and that the 1937 flood had inundated the business section to an average depth of 11 feet and caused local business losses estimated at more than $14 million.

In Men, Mountains and Rivers, his history of the Huntington District Corps of Engineers, river historian Leland R. Johnson quotes Markham as saying that while flood control projects obviously could be justified by the monetary loss they would prevent, it was his opinion that the real justification lay in “the saving of human life and suffering, and in the prevention of the disturbance of the affairs of the nation brought about by a flood disaster.”

Rep. George W. Johnson, D-W.Va., told the committee that Huntington was “eternally and everlastingly, every year” suffering flood damages far more than what local cooperation and generosity could afford and was ready and willing to contribute its share.

Rosenheim told the committee that Huntington, “if necessary,” would accept the responsibility of providing rights-of-way for a floodwall. “Huntington was hit awfully hard” in that year’s flood, he said. “But we need flood protection so badly that if it is impossible for the federal government to provide full payment, the city will undertake to provide the property.”

Congress ultimately approved a plan along those lines. Accordingly, the Chamber set about identifying the rights-of-way needed for the Huntington wall – and figuring out how to pay for securing them.

Huntington City Council voted to sell bonds to finance the land acquisition, then repay the bond money with the proceeds of a new “floodwall tax” that would be levied on all property the wall would protect. Perhaps not surprisingly, the tax plan drew objections – and a lawsuit. A Cabell County Circuit Court ruling upheld the legality of the bond sale and floodwall tax, and on April 9, 1938, the State Supreme Court unanimously upheld that ruling.

As planned by the Corps of Engineers, the Huntington floodwall was built in three phases, with separate sections protecting Huntington, Westmoreland and Guyandotte. Construction of the wall’s Huntington section began Aug. 1, 1938, and was completed in 1940, with work crews then moving to the Westmoreland section.

The outbreak of World War II prompted the Corps to halt all civil works projects so that material and workers could be shifted to military projects. The sole exception to that halt was the Guyandotte floodwall, deemed essential to protecting the plant of the International Nickel Co. (INCO). The plant was then busily engaged in war work, including the production of materials vital to the Manhattan Project, the top-secret effort that was building the atomic bomb. The 1937 flood had closed the INCO plant for six weeks; a similar shutdown during World War II could have meant a real setback for the war effort.

The Huntington Floodwall Board took over the operation and maintenance of the completed floodwall in 1943. That year, the floodwall prevented about $3 million in damages, and in March 1945 the wall saved the city another $3.6 million in damages.

On completion of the floodwall, a bronze plaque was placed at its 10th Street gate honoring “the public-spirited citizens whose vision and foresight” made possible the wall’s construction. The wall, the plaque reads, “was initiated by the Chamber of Commerce” and “designed and constructed under the supervision of the United States Army Engineers.”

Construction of the floodwall brought one negative side effect: with the wall blocking the Ohio from daily view, the city essentially turned its back on the river and forgot it was there. Fortunately, the construction of Harris Riverfront Park changed all that. Dedicated in 1984, the riverfront park represented a welcome rediscovery of the river by the community it helped create.