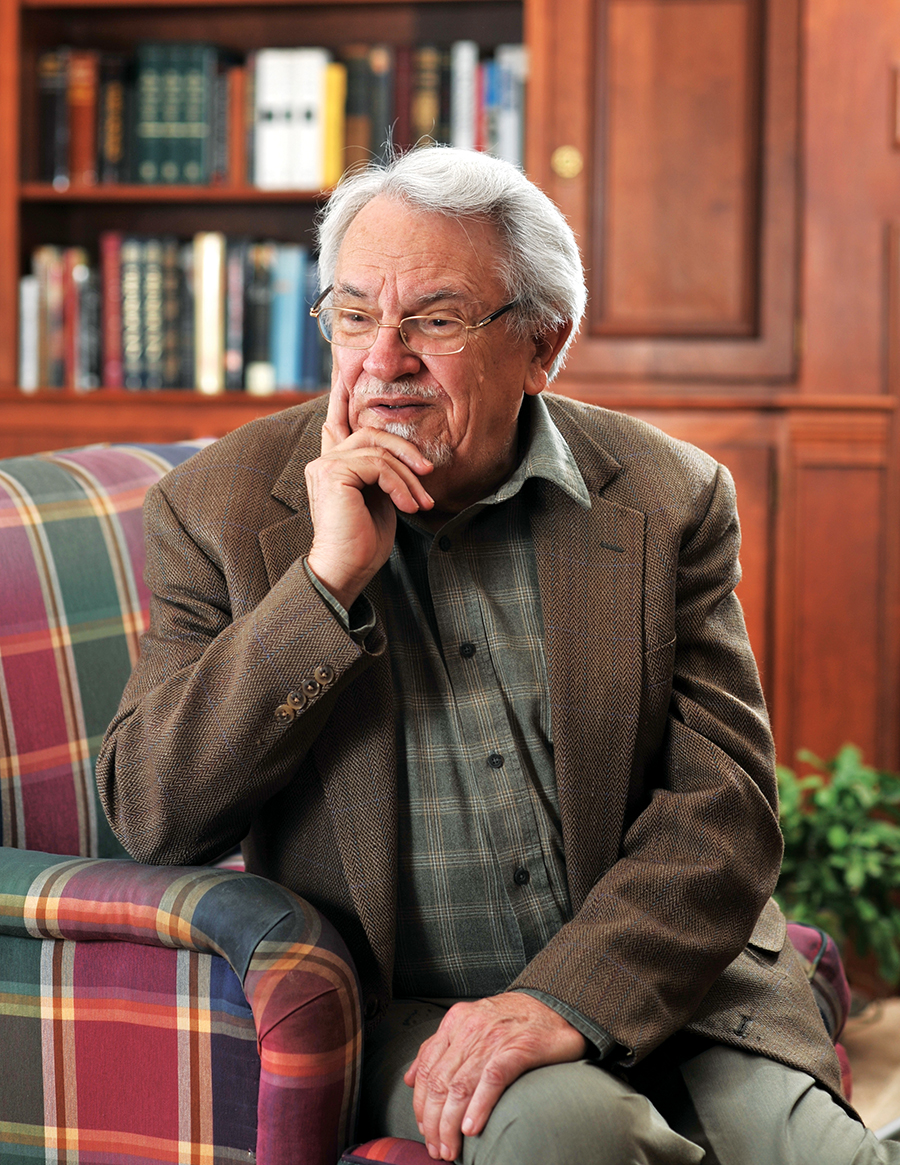

One of Marshall’s most legendary professors answers our questions on teaching and the state of politics today.

Interview by Katherine Reasons-Pyles

HQ 73 | SPRING 2011

You’d be hard-pressed to find a recent Marshall graduate who hasn’t heard of Dr. Simon Perry. And by “recent graduate,” we mean anyone who has graduated from the university within the last four decades. Perry taught political science at Marshall for 48 years, eventually retiring in 2010, a tenure that earned him the distinction of being the university’s longest-serving faculty member.

The thousands of students Perry guided over the years appreciated his insight into the inner workings of politics, the sincere love he demonstrated for his discipline and his challenging coursework — but what they cherished most of all were his stories. Balancing his seemingly paradoxical reputation for being one of Marshall’s most beloved and most challenging professors, Perry used every minute of class time to the fullest, intertwining personal anecdotes with his unparalleled knowledge of political theory and current events.

Born in Gilbert Creek, W.Va., where he says his parents were the first in the area to own a radio, Perry has lived and breathed politics since childhood. He received his bachelor’s degree in political science and history from Berea College, his master’s degree from the University of Tennessee and his doctorate from Michigan State University. In 1962, Perry’s doctoral dissertation, “Conflict of Expectations and Roles in ‘Policy Science’ Behavior,” received the American Political Science Association’s Leonard D. White Memorial Award for the best dissertation in public administration and related policy areas.

Perry dedicated his life’s work to higher education, beginning his teaching career at the University of Tennessee, continuing to teach at the University of Michigan and eventually accepting a position at Marshall in 1962. During his tenure at Marshall, Perry was awarded the Marshall Distinguished Service Award, was selected as the first Drinko Fellow by the John Deaver Drinko Academy and was twice named a Distinguished West Virginian — an honor bestowed first by Gov. Arch Moore in 1988 and then by Gov. Joe Manchin in 2007. He served as chair of Marshall’s Political Science department from 1975 to 1994 and is regarded today as one of the nation’s leading authorities on constitutional studies.

In this issue of HQ, we sit down with the now-retired professor in his Huntington home, where the walls of almost every room are lined with books, to learn a little bit more about Dr. Simon Perry’s many loves — teaching, politics, his family, Marshall and Huntington.

HQ: Earning an A in one of your courses was quite a challenge, yet students chose to take classes from you again and again. How did you manage to be one of the most beloved and most difficult professors at Marshall?

Perry: I think I got by with being a very demanding teacher because — and this sounds immodest — the students knew that I worked very hard. I also revealed a great deal about myself and my family, and I think students probably remember my stories, perhaps more than they remember the content of my classes.

HQ: What are three qualities every great professor must have?

Perry: I think one is that professors must love to learn. A professor needs to really love to learn to keep up with his discipline. Secondly, I think a professor needs to be informal rather than formal in the classroom. Thirdly, he needs to communicate his love for students — his interest in the welfare and future success of his students. I’ve tried to keep up with a lot of my students over the years. Probably 40 have obtained a Ph.D., and I’d say hundreds have obtained a law degree.

HQ: You’re known for speaking often in class about your wife Frances, a retired public school teacher who taught English, literature, science and math. How did she feel about being such a regular topic of discussion?

Perry: (Laughs) I think Frances has a very healthy ego. So she tends to enjoy my stories, even the ones in which I have her as the “loser.” She knows she’s been very important to me, and I think my stories remind her of that. I also told stories about my brothers and my family; I thought it was important to let students know a little more about me — who I am, who I was and some of the experiences I had growing up.

HQ: What sparked your interest in political science?

Perry: My parents valued the knowledge of current events very highly. We were probably the first family in Gilbert Creek to have a radio. Back in those days, when families were able to get a radio, the whole family sat around it and listened to the evening news. They listened together; there was no escaping each other. My father was such a Republican. During the 1940 election — the first election I can remember — my father wanted Wendell Willkie to win so badly. He got word that Willkie was coming to Huntington, so he made plans to travel 100 miles to Huntington to hear him speak. He came back and said, “Willkie’s got the election sewed up. There were 100,000 people who came to see him; they were sitting on the rooftops.” So on the day of the election, my father went out to persuade people to vote for Willkie, and he came home around 9 p.m. to hear the good news. He walked in and I said, “Dad, Willkie is behind.” And Dad said, “Simon, that’s the city vote coming in. Wait until the country vote comes in.” Roosevelt gained more and more of a lead, and I said to my father around midnight, “Dad, when is the country vote going to come in?” And he said, “Young man, you go to bed.” (Laughs) So, you see, I could not escape politics. It was in my household, in my father’s blood, and it penetrated every cell of my body.

HQ: Would you say that Roosevelt was the greatest president of your lifetime?

Perry: Yes, without question, although when FDR was first elected I was only a year old. I think I started remembering him around the year 1937, and I disliked him as a youth because of my father. I just assumed my father knew all things. Of course sometimes presidents move up and down long after they leave office; the public’s opinion certainly changes. Eisenhower was rated low at first, but he has really climbed up the charts in people’s minds, and Truman has climbed up to the near-greats as well. I would rank Truman in the “great” category, given all he did while he was president. Right now, the public is saying that Reagan was the greatest president; in my judgment, that really has a great distance from the truth.

HQ: How long does it take for the public’s true feelings about a president to be revealed?

Perry: If presidents are very controversial, or stereotyped by the media in a negative way, it probably takes 20 or 30 years for all of that to wear away. In that time there will be biographies written and all kinds of political analyses done of their work. Their work will be seen either more favorably or more disfavorably depending on the consequences that took place as a result of their actions. There is a tendency, too, to overrate those who were president during one’s lifetime, which is an obvious advantage that a present-day former president has over one who served years ago.

HQ: Did you ever think you would see the day when America would elect a black president?

Perry: No, I would not have foreseen that. I really think that America has gone through a period of great prejudice, in both the North and the South. A lot had to be overcome before a black person could be elected president. Obama, though, had such charm and charisma; his personality made the country more accepting of a black candidate. America has changed a great deal since the civil rights movement, but I still think there’s a lot of prejudice out there. There are a lot of Americans who probably want Obama to fail.

HQ: What effect do you think talk radio has had on politics in America in the last decade?

Perry: Talk radio is inflammatory. Each side tends to harass the other, and in terms of factuality and the real world, it tends to be way off course. I do not feel that talk radio is the best way of finding out what’s going in the world. Whether the talk show is from the left or from the right, it is just not the way for citizens to discover the truth. The truth is out there, in books and journals and in objective reporting.

HQ: In West Virginia Democrats outnumber Republicans 2-1, yet the state has gone red in the last three presidential elections. How do you explain that?

Perry: I’ve been asked to explain that a dozen times. That is really difficult. My own conclusion is that it deals with the issue of energy, especially coal. Obama does not offer a lot of hope to West Virginians with regard to that aspect of our economy. I think that probably creates a negative disposition toward Democratic presidents, since Democrats seem to be more concerned with cleaning up the environment. I also think that West Virginia tends to be a little bit more like the South than it does the North. And while Obama carried Virginia and North Carolina, in West Virginia I think the prejudice that exists in combination with the energy issue was enough to prevent him from winning our state. However, there are some studies which show that in southern counties of West Virginia, where you’d think the question of energy would be the strongest, the Democratic candidates continue to prevail. It is truly a difficult question.

HQ: Do you think political discourse in America is less civil today than in the past?

Perry: It depends on what part of the past you’re talking about. The civil discourse during the early days of America, under the new Constitution, was unbelievably bad. The Jeffersonians just demeaned the Federalists. They portrayed Hamilton, Washington and John Marshall as monocrats wanting to establish monarchy again in the United States, and that was a very serious charge. Then, during the New Deal, the Republican party accused FDR of leading us down the road to socialism. Today, civil discourse is really bad; there is no doubt about that. I would say that as bad as it has been in the past, it is just as bad, or worse, today.

HQ: You are unanimously regarded by your former students as one of the world’s greatest storytellers. How do you integrate your love for storytelling and your love for politics?

Perry: You can really bring politics to life if you give it a story. I tried to remain very loyal to my discipline, but I wanted to bring my discipline to life through stories whenever I could.

HQ: What are some of your earliest memories of teaching at Marshall?

Perry: When I first came to Marshall, we had approximately 4,000 students. We had 11 buildings, and one of those buildings had been a grocery store. The political science department was located on the third floor of Old Main, along with the English department. We had to share a telephone with the English department. We had to share a bathroom — a very small bathroom — with the English department. Eventually, the English department, with Professor Eric Thorn in charge, became very aggressive. I’ve often referred to Eric as the secretary of war. He took every square foot of the third floor that he could get. One day, workers came to our offices and said, “We have been ordered to close down the bathroom.” And they proceeded to turn our only bathroom into an office — for a professor in the English department. I have no idea where we went to use the bathroom after that; I think we had to walk to the second floor. Eric eventually took the whole third floor through his imperialistic efforts, and they sent us over to Smith Hall.

HQ: During your 48 years at Marshall, how has the university changed?

Perry: When I began at Marshall, the faculty was very close to each other and especially close to students, but I think that’s still the case today. The school has become more complex; it has so many more programs. There is still a great stress on teaching at Marshall, but research has become increasingly important. And I think that helps to make a great university. We’re not among the elite schools yet, but let me stress the fact that Marshall uses the same books as Harvard and Yale; we use the same journals as the top schools, and we probably devote more time to teaching well. The only differences between the country’s top schools and Marshall are the stress by the elite schools on research and the presence in those schools of unbelievably talented students. We have a lot of very talented students; they have almost all very talented students.

HQ: How have the demographics of the student body changed?

Perry: The beneficiaries of the greatest changes at Marshall have been women and blacks. When I came here, women had to be in by 7:30 on weeknights. They could gain special permission to be out later than that on the weekends — but the men could come and go as they pleased. I would die if I had to be in my room at 7:30, but women had to endure that. Now I think there’s absolutely no difference between women and men in the way the university treats them. Additionally, we had about 40 African-American students when I came to the university, and they had a tough time on campus. There were no blacks in any organization, no black cheerleaders, no lack majorettes. African-American students could not rent rooms off campus because some of the landlords would not rent to them. I was chairman of a committee set up by the president of the university called the Human Relations Board. We conducted studies on landlord prejudice and the way blacks were treated on and off campus, and I think we did bring about some changes. Now there are around 800 black students on our campus.

HQ: What do you foresee for the university’s future?

Perry: I think the university will grow extensively in the future. It will direct a push toward the river and probably the railroad tracks. It will become more research-oriented and will develop many new programs. As we develop new programs, various publics will become dependent on those programs, and therefore they will support those programs. Support will come from the community at large, the legislature and the governor. Research is the way for a university to grow and develop; it adds to the power of the university.

HQ: This issue of HQ features an article on our favorite former eateries. What are some of the places you remember frequenting during your early years at Marshall?

Perry: My brothers owned a very fine restaurant at the top of the West Virginia building. It was my favorite restaurant, not because my brothers owned it, but because I thought the food there was outstanding. And of course Rebels and Redcoats was terrific also. Back then I was a steak eater, maybe an unimaginative one. I loved the steaks at Rebels and Redcoats, and I loved their entertainment. It was a place where you could go to dance with your wife.

HQ: What would you say was your biggest accomplishment during your teaching career?

Perry: That is hard to say. Truthfully, I just loved writing a new lecture. Preparing my lectures probably gave me more pleasure than actually delivering them. I was the first Drinko Fellow, and of course I was very proud of that. I wrote a little book during that process. I was invited to give the winter commencement address, and I thought that was quite an honor as well.

HQ: You accomplished so much during your teaching career, from shaping the lives of future politicians, lawyers and journalists to publishing your findings on justice and inequality. Is there anything you plan to add to your legacy during your retirement?

Perry: I have had some trouble getting used to retirement. It is nice not having to face a schedule, not always having to be somewhere on time. I have the freedom to write at my own leisure, to reflect. But I still want to meet other people. I want to help others. I want to have goals and to live a full life, right up to the very end. When we are young, we feel that we have thousands and thousands of days left, so we can say, “I’m not going to do that today, and tonight I am going out.” But when you get old, you realize that the days you have left are few in number, and you tend to treasure those days greater than ever. You know when each day ends, it is gone forever. I would like to write a book on what I feel are the seven great moments in American history and see if I can determine if there is a unique kind of politics that characterizes each moment. I just finished a paper on the Founding Fathers and religion; it’s being typed up now and will be published by the Drinko Academy. I would like to travel a little bit more and see my family. I have seven granddaughters; they are in my heart fully, and I love them dearly. I also just became a great-grandfather to a little girl.

HQ: The final class of your career, American Government, held on Friday, April 30, 2010, was attended not only by your current students but also by your colleagues, family, friends and former students. How did it feel to realize just how many lives you had touched?

Perry: I had no idea that this was happening. I walked downstairs to deliver my final lecture, and reporters from the local news stations were there. Standing in the back of the room was the dean, along with some of the other faculty. Our university president was there. I thought I would die, but I knew I had to give my last lecture — in a room full of around 60 people. I felt so honored and overwhelmed by that. I enjoyed it very much.

HQ: What would you say you love the most about Huntington?

Perry: You know, a lot of people talk about Lexington being such a beautiful place. Of course it is, with all those farms. But Huntington has at least three things that Lexington does not have. We have a beautiful river, we have mountains and we have wide streets. Those are three things I really like about our city; they are a few of the things that make our city truly great.