Legendary Marshall Coach Cam Henderson was not only a master of football & basketball, but one of the greatest in sports history.

By Ernie Salvatore

HQ 15 | SUMMER 1993

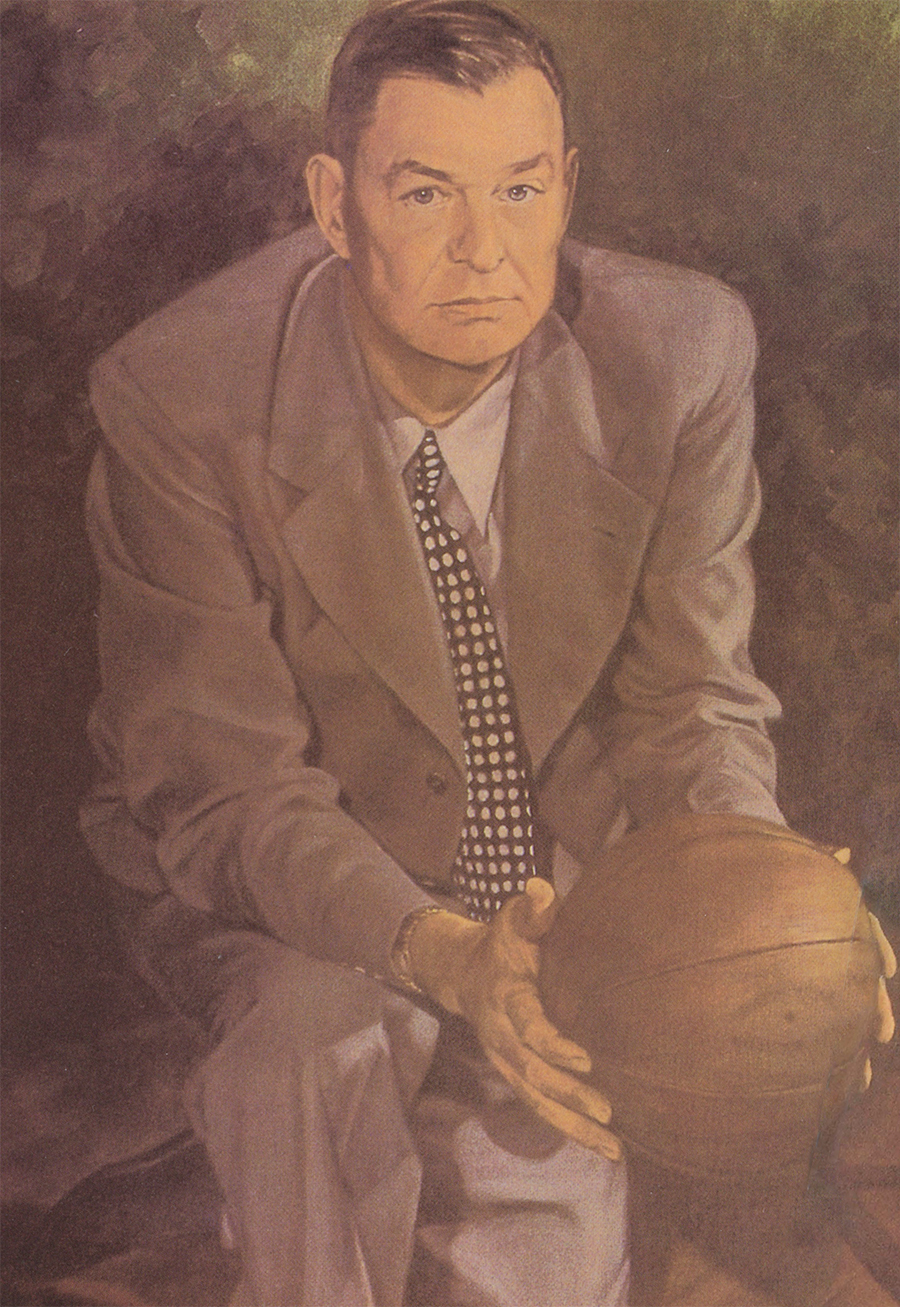

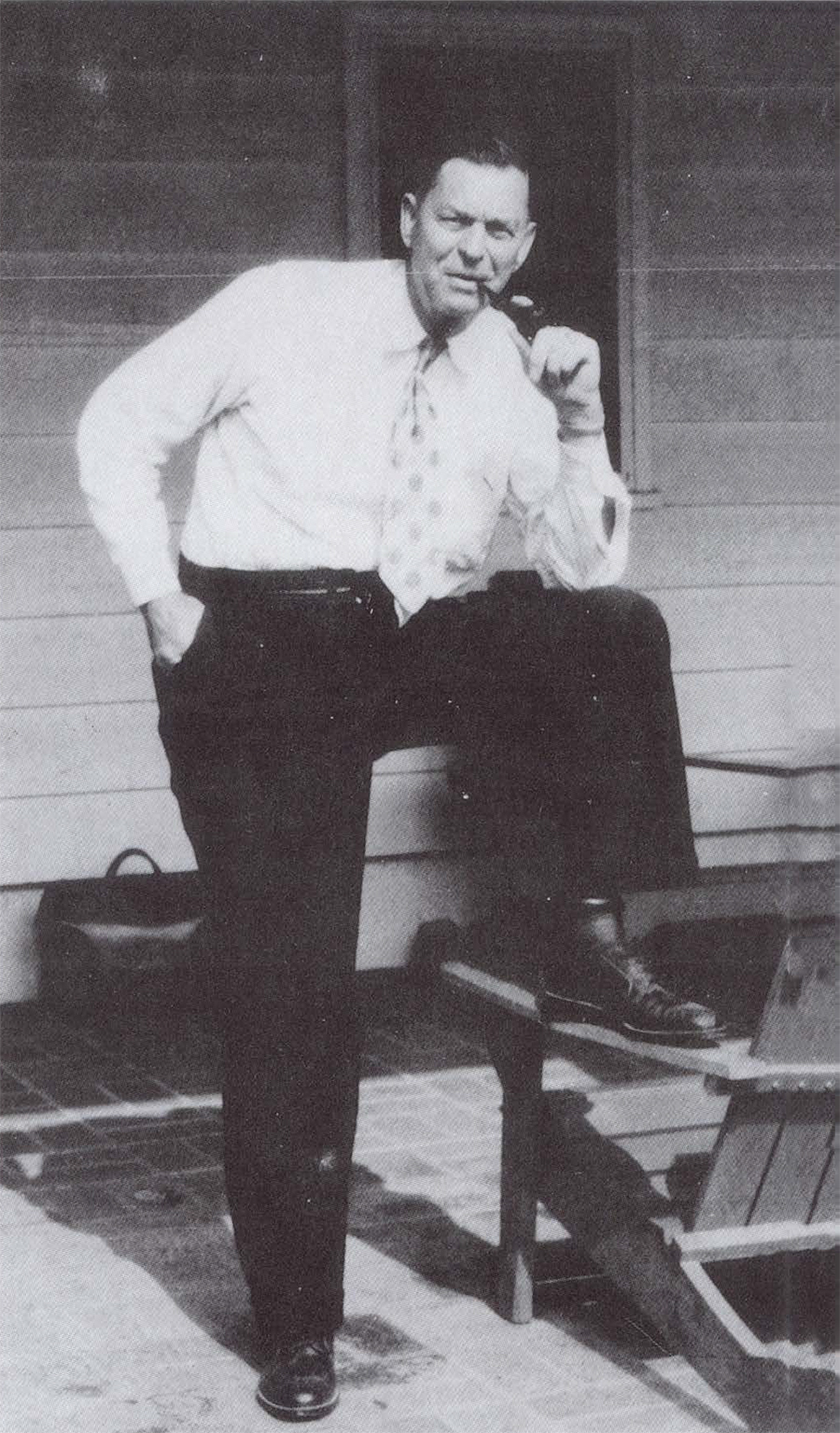

Cam Henderson didn’t look like a coach. He looked like a country-boy school teacher, which he was early on. He was tall and rangy, with a gentle, almost shy smile and a twinkle in his eye which he could turn off instantly – like a light switch. Then what followed was neither shy nor gentle. It was legendary.

Legends, I’ve learned, are like old soldiers. They never die, they just fade away, quietly and gently, into the realm that awaits us all.

Cam Henderson followed that course at Marshall. Today, sadly, he’s become an undefined proper noun over an arena entrance facing Third Avenue. And, the ranks of those who knew him are fading away too.

Eli Camden Henderson, a.k.a. “The Old Man” or “Crafty Cam,” was simply the most successful two-sport college coach in an era when they were quite common. The record books tell us that. They tell us that 37 years after his death he still ranks among the Top 25 all-time college basketball coaches with a 583-216 career record that is 23rd in winning percentage and 20th in victories.

The books also tell us that in his 20 seasons at Marshall his 362-160 record included the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball championship (today’s NAIA), one Los Angeles Invitational (he nipped Syracuse at the buzzer in the finals), three straight Buckeye Conference titles (today’s MidAmerican) and 14 consecutive winning seasons.

The Los Angeles Victory was of special significance as further proof of Cam’s coaching versatility, because while he was in Los Angeles with his basketball team, his football team was in Orlando, Fla., with assistants Roy Straight, Joe Pease and Sam Clagg, to play Catawba New Year’s Night in the Tangerine Bowl. Cam wasn’t the only absentee. So were two-way end Bob Koontz and fullback-defensive end Norm “Wild Man” Willey, destined to become a 7-time All Pro with the Philadelphia Eagles. They were with Cam in California. Koontz was a high-scoring forward and Willey “the enforcer” coming off the bench. Their absence in Orlando, many of us felt, led to the Herd’s 6-0 defeat – its lone shutout after averaging 31 points a game in regular season play.

His 1946-4 7 team was, by many accounts, bis best and most popular. It not only won 32 of 37 games, the last five winning the NAIB title, but it set off the biggest spontaneous sports victory celebration in the history of the region. Maybe the entire state.

Police estimated that more than 15,000 people were massed around the C & 0 Railway Station that March night in 1947 to salute their conquering heroes and listen to Cam Henderson’s speech …

“That was some speech,” Bill Toothman said. “The Old Man charmed the whole 15,000. But what he forgot to tell them was how he spoiled our own private victory party back in Kansas City. We’d arranged it with the manager of our hotel. Win or lose we were going to celebrate with beer and sandwiches. After what we’d been through we figured we earned it.”

The Old Man didn’t. As soon as the presentation ceremonies in the Kansas City’s Municipal Auditorium were over, a fleet of taxis was waiting to take the players to the hotel for their luggage, then to the railroad station to catch the train for Huntington.

“We didn’t even change into street clothes until we got on the train, “Toothman chuckled. “And we didn’t get to shower ’til we got home 24 hours later!”

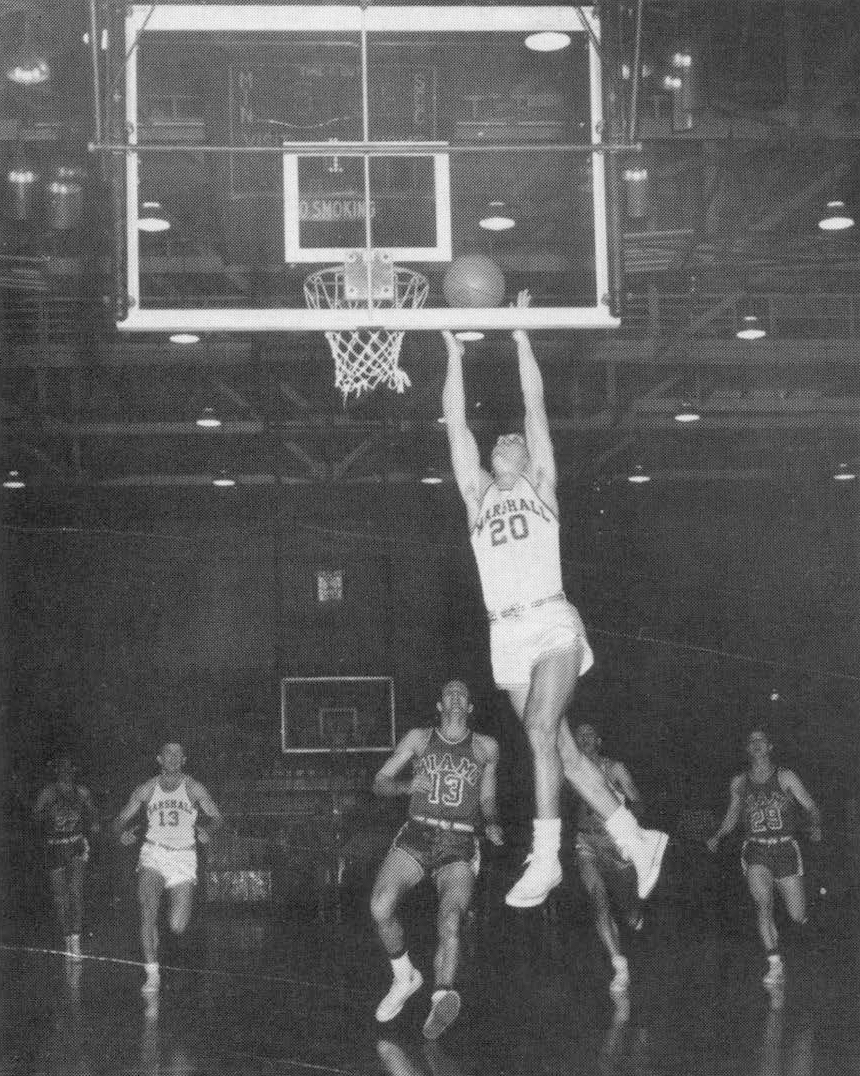

Out of all this came six All-Americans. Two, Jule Rivlin and Hal Greer, went on to professional stardom! Greer, the former Huntington Douglass High School star was, of course, Cam’s best ever “catch.”

It was also his most historic as Greer was the first black to breech West Virginia’s color line at so-called “white schools.” That was in 1954.

An odd twist of fate followed Greer’s recruitment. He never played for Cam. He played for Rivlin who succeeded Cam, his old coach. But that’s another story for another chapter in this series.

On the football side, Cam’s 12-year 68-46-5 record remains Marshall’s best. Thus, sports history must conclude that as a coach, an educator and theorist he accomplished more with less than any of his celebrated contemporaries and mainly because he wanted it that way. Excess troubled Cam. He saw it as a deterrent. Simplicity and hard work were his gods.

Take, for example, a night in 1947. Henderson is scouting the University of Louisville Cardinals basketball team. His companion is Dr. Sam E. Clagg, a solid two-way football lineman of Cam’s and now his assistant. A football assistant? On a basketball scouting mission?

“He sat there eating popcorn, watching the game,” Sam recalled. “He never said a word and he never took a note. Finally, by the half, he’d finished his second box of popcorn and turned to me and said, ‘Let’s get out of here, Sam. I’ve seen all I want.’”

A week later the Herd blitzed the Cards, 62-55, in smoky old Vanity Fair.

Other examples of Henderson’s genius abound. Start with the zone defense that still plagues basketball offenses today and is outlawed in the NBA. Cam invented it in 1914 as a 23-year-old rookie coach at Bristol High School in West Virginia. Ten years later he applied the same principles of the “zone” to college football at Davis & Elkins. He brought it to Marshall in 1935 decades before Stagg, Rockne or Warner thought of it.

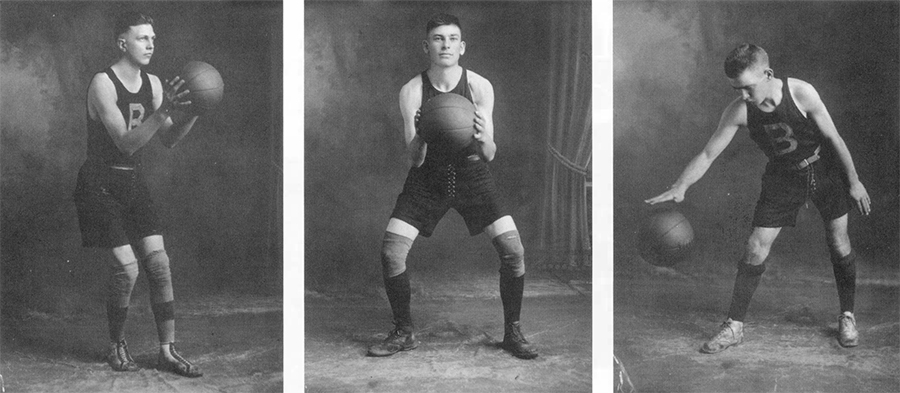

The three-man basketball fast break is another Henderson original, only he called it the “quick break,” introducing it at Muskingum (Ohio) College shortly after World War I as an offspring to his zone defense.

He reasoned, correctly, a “quick break” in the opposite direction by the team coming off a zone would force the opposing team to chase its own missed shot into a sudden retreat running backwards. Today, this is called “transition” basketball.

Cam soon saw that speed and agility would have to be the two most important qualities in his players if his zone and quick-break were to work. So, he devised lengthy, non-stop practices to develop speed, stamina and mental toughness, triggered by the ball handling magic of his middleman, or point guard, running the break. Thus, the behind-the-back pass was born (another Henderson original) a half century before Bob Cousy, the Boston Celtics icon, “introduced” it at Holy Cross.

Jule Rivlin, Marshall’s first All-American, indulged in that wizardry in old Vanity Fair in the late 1930’s. Ditto for Toothman, Cebe Price and Walt Walowac. Only practice, practice, practice could perfect these skills, Cam knew.

Walowac, a great outside shooter of the pre-3 point goal era, remembers practicing on Christmas Eve.

“It didn’t make a difference to the Oki Man,” Walt said. “Saturdays, Sundays, holidays. Morning, noon and night. You never knew. So you had to be ready. The thing was, this time he put me in charge of the practice.

“It was 1953. He calls me in and gives me the keys to the Field House and tells me to run our two and one half hour practice without him. I know it was Christmas Eve because when we got to the Field House they’d already put up a Christmas tree at one end of the court. “

But Walowac obeyed Cam’s orders to the letter.

“We did it all,” he said. “Fast breaks. Half-court offense. Full-court offense. Defense. Ball handling. Shooting. Run, run, run. Two and a half hours! Then I blow the whistle and say we’re through and a voice in the balcony yells, ‘Whoa, down there! Whoaaaaa.’ It was the Old Man. He’d been hiding behind the seats up there watching us. He came down and ran us for another hour and a half!”

As in basketball, Cam kept things relatively simple in football. He rarely used more than a half dozen running and passing schemes – his defensive sets, no more than four, maybe.

Working with such contemporaries as Carl Snavely of Cornell and later North Carolina, Dick Harlow of Harvard and Bo McMillan of Indiana, he helped design a single-wing offense that featured a spinning fullback alongside the tailback. Every play began that way. It froze the defenses and gave the ball carrier and his blockers a half step head start.

A strong case can still be made by old timers that Cam’s 1937 team was Marshall’s best ever – with all due respect to last year’s 1-AA national champions. Not only was it undefeated (it played one tie) in 10 games, it won the Buckeye Conference and indirectly lead to its breakup after the 1938 season. It also sent six men to the National Football League including the starting backfield!

End John Stephens signed with the Cleveland Rams, tackle Frank Huffman, the Chicago Cardinals; halfback Jack Morlock and tailback Herb Royer, Detroit; fullback Bob Adkins, Green Bay; and halfback Lee “Boot” Elkins, the New York Yankees (today’s Indianapolis Colts:)

But Royer, who the Old Man said was “my brains on the field,” didn’t stay with the Lions for long.

“I was on my way back to Detroit,” Royer said, “and I’d stopped in Huntington to pick up some things and say goodbye to the coach. But when I go in to say goodbye to Cam he comes right to the point.

“‘Royer,'” he says, ‘I need a backfield coach and I’m offering it to you. How about it?’

“I tell him ‘thanks but no thanks.’ After all, my chances with the Lions were too good to pass up and I needed the money. ‘Forget the pros,’ he says to me. ‘They’ll never amount to a damn!’ So I took Cam’s offer.”

Royer’s quick capitulation was understandable. An aura of omnipotence had risen around Cam Henderson, fueled in part by his spectacular coaching successes.

People gravitated to him but they also kept their distance. His players feared and worshiped him. Even today, as aging men, they speak of him in reverent tones as if he were some kind of demigod.

Actually, he was a private person, given to too much secrecy and with modest tastes in drink, food and entertainment – all of which made him a sportswriter’s nightmare.

But he also cared about people, especially people dear to him – like his players or his family. And to the end, this coaching genius remained what he’d always been – a plain, down to earth country-boy school teacher.

In 1936 at the start of his second season at Marshall, Henderson was on the first of what would be annual basketball trips to New York to play the best in the Big Apple. On the morning of the first day he was given some bad news. Buck Jameson, his star, was in bed with what appeared to be the flu.

“I was Buck’s roommate on the road,” said Royer who, like many athletes back then, played more than one varsity sport. “Buck gave me a couple of dollars to buy him a half-pint of whiskey. That was the cureall for all country people in those days. It was Buck’s plan to sweat out his flu with the whiskey.”

Well, Buck had barely gotten a third belt into his system when there came a knock at his door. In strolled Cam with Kerr Whitfield, his athletic director. Cam quickly felt Buck’s forehead, said he was too ill to move and handed Royer three dollars with instructions to buy Buck a half-pint of whiskey.

“Put him in his sweat suit, pile the covers on him and have him sweat out that thing with the whiskey, “Cam said. “He’ll be fine in the morning.”

In the morning Buck’s bed was soaking wet, he was 10 pounds lighter and more hung over than cured.