Huntington son Alex Schoenbaum is the man who built the Shoney’s empire

By John H. Houvouras

HQ 18 | SUMMER 1994

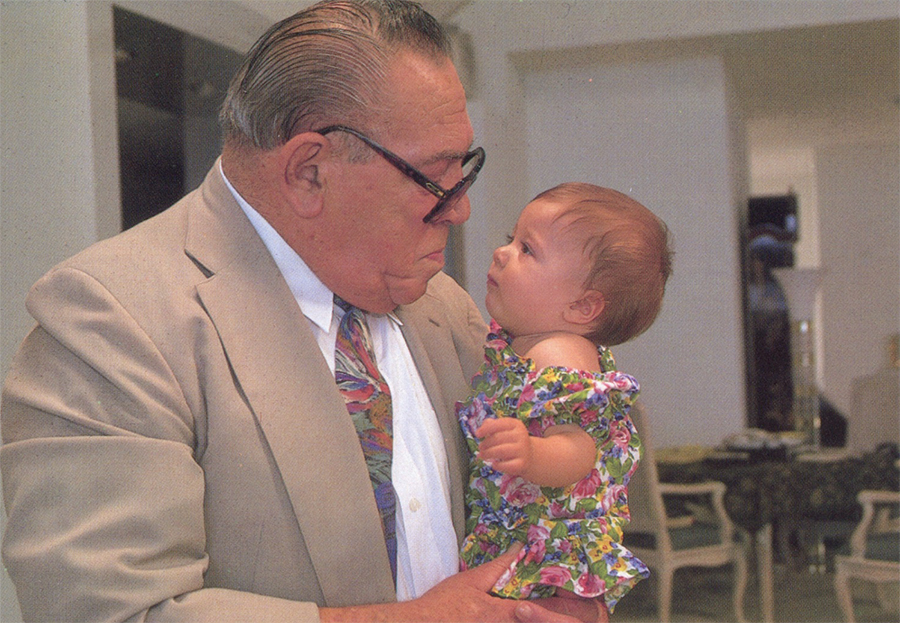

A balmy Florida afternoon finds Alex Schoenbaum at home, seated on his favorite couch overlooking the crystal blue waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The faint laugh of a grandchild at play can be heard somewhere in the background of his large, exclusive Longboat Key condominium as he readies his thoughts.

“I guess the secret to my success has been my ability to get along with people,” he reflects. Rising slowly from the couch, he lumbers over to the balcony, limping somewhat along the way, evidence of his battles on the football field where he was a three-time All American. A giant in his day at six feet tall, 230 pounds, he still retains much of his stature at the tender age of 79. “Have you ever seen such a beautiful view?” he asks.

People do not describe him as diplomatic, but rather tough, gruff and crusty. He is the kind of man who often wears gray suits and red ties, his Ohio State colors, even when attending a West Virginia University football game. A rugged individualist, he is, nevertheless, most likable.

He is Alex Schoenbaum, the entrepreneur, philanthropist and restaurant mogul credited with popularizing the family-style restaurant in America. If you have ever tried the all-you-can-eat salad bar or the All American burger, you have seen his vision. He is the man who built the Shoney’s empire.

Born in Richmond, Va., on August 8, 1915, his father moved the family to Huntington in hopes of better business opportunity when Alex was 10. Growing up on the South Side – they lived in four different locations from Eighth Street West to Second Street West- Schoenbaum and his three brothers, Howard, Leon and Raymond, quickly became involved in athletics. “At first, we were exposed to being called all kinds of names,” he recalls. “We were Jewish and we were kind of different on the scene I guess. We had to fight our way up. We seemed to be able to get into fisticuffs very easily.” But as the Schoenbaum boys’ prowess on the playing field progressed, so too did their stature in the community. Looking back at the move to Huntington, Schoenbaum says, “We loved it.”

But despite their reputations throughout the city as good athletes, the boys still found time to stir up some trouble.

“Back in the old days, everybody had an ice box, not refrigerators,” Schoenbaum says. “And we used to go ‘fridgeting’ or ‘ice boxing’ on peoples’ back porches and raid their ice boxes. We would eat anything we could get our hands on. Or if there was a PTA meeting at night, we would go to where the cars were and let all the air out of the tires. Yeah, we used to get into trouble.”

He describes his parents as just ordinary people who cared deeply about their children. “They certainly didn’t like the idea of us participating in athletics because they were afraid of us getting hurt. It took a lot for my parents to finally go to a game.”

Schoenbaum’s father Emil, a Russian-Jewish immigrant, owned Arcade Recreation – a bowling alley and poolroom in the basement of Huntington’s arcade. Schoenbaum remembers him with affection. “He was a very personable man, accepted by everybody. He also was a musician and made friends out of a lot of people.”

“Papa wouldn’t allow any cussing,” recalls Betty Schoenbaum, Alex’s wife of 54 years. “He ran a tight ship.”

Remembering the most important thing his father taught him, Schoenbaum says, “honesty. And, treating your fellow man well. But I also think the biggest thing he did was make a living for his four sons and his wife in a very difficult time – during the Depression. Things were real rough. I don’t think he paid rent for three years to the Ritters.”

With his father working hard to make ends meet running the bowling alley, the Schoenbaum boys were often brought in to lend a helping hand.

“We boys, I in particular, spent a lot of time learning how to set pins,” Schoenbaum says. “I was a damn good pin boy. My father would match whatever I would make – if l made a nickel, he would give me a nickel. So, I was able to save money. I was very ambitious as a young person.”

Along the way, Schoenbaum learned the value of saving money and quickly became quite adept at the science.

“When I was seven or eight years old, we used to get ,. money to go to the movies. But I didn’t spend mine. I kept saving it. And if Dad was buying us ice cream cones, I took the money and didn’t eat. I was able to save up money and buy things I really wanted. It was very interesting because it taught me to be very conscious of real small money. And it’s been that way all my life unfortunately. I don’t think I’ve ever told anybody this but I’m very careful with a nickel or a dime. I can give away big money and yet I am very aware of small, spending money.”

Schoenbaum attended public school at Cammack and later excelled as a two-sport star at Huntington High School. He was, by all accounts, a stellar athlete.

Jack Glick, who used to run around with Schoenbaum, remembers him as rough and tumble.

“Alex was six feet tall, 230 pounds,” Glick says. “That was real big in those days. But, he was a gentle giant. I remember that he did all the punting and kicking for Huntington High School. He could kick the ball 60 yards off the tee, no problem.”

One of Schoenbaum’s crowning achievements came during his second year at Huntington High when the Pony Express locked horns with the undefeated Ashland Tomcats.

“People in Huntington might remember that Ashland and Ironton used to have great football teams,” Schoenbaum recalls. “Ashland hadn’t lost a game for years and then finally we played them and beat them 7-6. And I kicked the extra point that won the game. That was a big deal not only for the school, but for the city and it was a big deal for me. My foot became pretty damn valuable. It was the talk of the town. We had quite a football team,” he boasts. “The line averaged about 220 pounds. That was pretty big back then.”

It wasn’t uncommon to see Schoenbaum’s father in the stands rooting his son on, informing the crowd, “That’s my boy Alex. Raymond is your boy, Mama.”

At the end of his second year at Huntington High, Schoenbaum had made All-State on the football team and played on the basketball team.

“I thought I had reached the top of the heap athletically,” Schoenbaum says. “As a result, I was dumber than I could be because the coach would always get the teachers to take my name off the ineligibility list. Therefore, I didn’t have to study because they were babying me,” he readily admits. “I finally realized after a couple of years that I wasn’t getting anyplace so I decided to go to prep school to learn how to study.”

In 1933, Schoenbaum left for Kiskiminetas Springs Prep School in Pennsylvania. Not having enough money to enroll, he worked his way through school selling sandwiches and waiting tables – the foundation for what later would be his career. “I bought cold cuts for 5 cents and sold 10 cent sandwiches.” In addition, a major university had offered to pay Schoenbaum’s way through school in return for future football favors. But at the end of his first year at Kiskiminetas, the dean of men and one of the owners of the school offered him a better deal to remain at the school for another year and play football.

“That was one of the great years of my life because I actually did learn how to study, thank goodness, and was eventually able to get through college.”

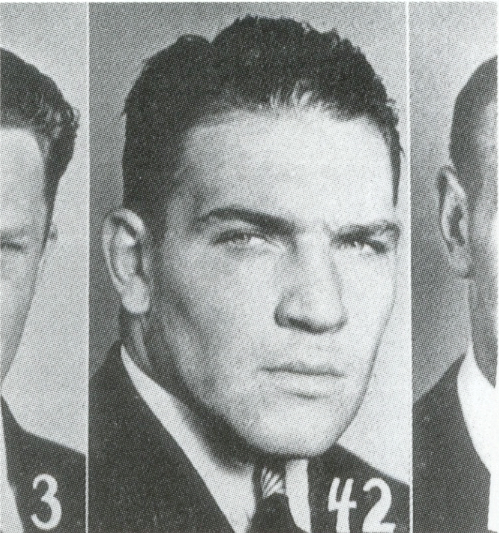

Upon graduation from Kiskiminetas, Schoenbaum selected Ohio State University and enrolled in 1935 on a football scholarship. He played tackle for four years, garnering Grantland Rice All American Football team honors three consecutive years. When introduced recently at a fundraiser as an All American football player, Schoenbaum quipped, “Yes, I am an American all the way. That’s more important than being a football All American,” he added.

At Ohio State, Schoenbaum was the quintessential “B.M.O.C.” (Big Man On Campus). A highly-touted football player, he also was an honor student. And while he has many fond memories of his four years in Columbus, his fondest, he asserts, was the first day of school.

“That was the day I met my wife,” he says with a smile.

Betty Frank was a freshman unpacking boxes in the lobby of her dormitory amidst hundreds of people when she first encountered Alex Schoenbaum.

“I came down the stairs and here was a guy in a beige, gabardine suit,” she recalls. “He was a big fella, probably a senior I figured, and so I asked him for directions to the Phi Sigma Delta fraternity where there was a big party planned. And the first words my husband ever said to me were, ‘Are you Jewish?’ And I didn’t answer him. I thought it was a rude thing to say. I went ahead and found where the party was.

“We ended up meeting again at the party,” she continues. “I asked him, ‘Why would you ever ask a girl that? That was rude.’ And he said, ‘My mom wants me to marry a nice Jewish girl.'” They began dating soon thereafter.

Schoenbaum finished his studies at Ohio State in 1939 and immediately went to work as a car salesman in Columbus. And as he likes to recall, his college sweetheart was turning up the heat for a more permanent commitment. “After graduation, my wife was in a hurry to get married so … “

“Hey,” Betty interrupts, “I had been going with him for four years, engaged two years, it was time!”

“So,” he continues unaffected, “I sold cars for about eight months and was very successful and sold insurance for several years.” They were finally married in 1940.

Schoenbaum’s success in the insurance business was interrupted in 1941 at the outbreak of World War II. His three brothers entered the service and his ailing father was left alone to manage his growing business which had expanded to Charleston. Schoenbaum attempted to enter the service as well but was rejected. “I went down to enlist and they turned me down,” he recalls. “I had a bad back. Uncle Sam didn’t want me.”

He returned to Huntington in 1942, planning to help his father until his oldest brother returned. Remembering the time, he pauses for a moment, then continues. “My oldest brother was killed in the service. He was supposed to run the business for my father. But he never came back.”

As a result, Schoenbaum eventually left Huntington to run the family’s growing bowling center in Charleston. He would remain there most of his life.

For five years, Schoenbaum managed the family’s business in Charleston, often working 18 hour days. But in 1947, a dream of opening his own business was finally realized. “Parkette” was the name given a 1950s-style drive-in restaurant he opened adjacent from the bowling center in Charleston. Early on, Schoenbaum was looking to the future.

“I felt women were going to be working, there would be two incomes in the home and there was going to be a need for a drive-in or eating out facility. And the country was becoming more mobile with the automobile. I thought that was the route to go.”

Before the 1950s, “Mom and Pop” places dominated the restaurant scene in America. Franchises were few and far between. The days of McDonald’s had not yet arrived.

His first restaurant consisted of nothing more than a 20 x 24-foot building which offered curb service. But after only 14 months, Schoenbaum had done so well with the concept that he tore the place down and built a bigger facility. It still offered curb service but was more accommodating with 11 stools inside. Schoenbaum fondly recalls those first months.

“We paid a car hop a dollar a shift, so the labor costs were pretty damn cheap. We did real well. After a couple of years, we raised the car hops to two dollars a shift. We were still profitable.”

In addition to building a business, Schoenbaum was also building a family. The coming years would bring four children: Raymond, Jeffry, Joann and Emily.

Schoenbaum’s strong work ethic continued over the years as he began to shape his empire. James Prennis, his former right-hand man at Shoney’s, recalls that he arrived at work at dawn and it wasn’t uncommon for him to drive employees home after midnight.

“Alex knew the meaning of hard work,” Prennis recalled. “On a typical Saturday night, you could find him on the parking lot, picking up trays in the rain, his wife asleep in the car.”

Prennis also remembers that Schoenbaum often used his intimidating stature to take care of business.

“You know, Alex is a big man,” Prennis said. “When he managed the family bowling alley next door to the first restaurant in Charleston, I remember him carrying out two men, one in each hand, their feet dangling off the ground. And they were two pretty goodsized guys. Apparently, they were causing some trouble and Alex was cleaning house.”

In 1953, Schoenbaum held a contest to change the Parkette name. The winning idea would receive a new Lincoln automobile. “Shoney’s” was the name Schoenbaum selected.

The popularity of Shoney’s caught on quickly. “The demand and the pressure was so heavy that we had to open another location to take some of the heat off,” Schoenbaum recalls.

He began by opening another Shoney’s in Charleston, then one in Kanawha City, one in South Charleston, and yet another downtown. From there he moved on to Huntington and Parkersburg. “Those were our first two ventures out of the city.”

The former “Big Man On Campus” acquired his first Big Boy franchise in 1951, renaming his restaurants “Shoney’s Big Boy.”

“We wanted a merchandising tool,” Schoenbaum says, “and Big Boy was very good to us.”

Schoenbaum’s empire continued to expand on a regional basis. When an employee predicted that one day Schoenbaum would have more than a hundred stores, the restaurant mogul laughed. “I told him he was crazy,” Schoenbaum says. “But it didn’t take too long before we were there. As we got bigger, we were able to get better people and that is an important key to success – having good people.”

In 1971, some 24 years after opening his first restaurant, he merged with Danner Foods, a publicly-held corporation in Nashville, Tenn. The two entities became Shoney’s Big Boy Enterprise. From 1971 to 1976, Schoenbaum was instrumental in the growth of the new organization, serving as chairman of the board. In 1976, the company became Shoney’s Inc. and Schoenbaum was named senior chairman. He retired in 1985 but remains active in Shoney’s affairs as a director and member of the executive committee.

Today, with 1,800 restaurants in 36 states, Shoney’s is the nation’s third largest group of family restaurants. Included in the restaurant dynasty are Shoney’s, Captain D’s, Lee’s Famous Recipe Chicken, Fifth Quarter Steakhouses and Pargo’s.

Over the years, Schoenbaum has accumulated more than 3.3 million shares of stock in the company he helped found. This year, the stock has been as low as $14 per share and as high as $25, making his personal worth in Shoney’s stock alone nearly $84 million.

“My philosophy always was to give the most food of quality for the least amount of money,” Schoenbaum reflects. “We are still doing it.”

“He has always wanted to do things better than other people,” notes wife Betty. “He insists on doing the job right.”

And that includes everything from Shoney’s nationally-known salad bar to their world-famous strawberry pie.

“The pies must always have fresh strawberries, even if it means a special air shipment from California,” says Schoenbaum. “That’s the way we do things.”

“It’s the old school, the Depression years, the ability to do whatever it takes to get it done,” notes son Jeff, regarding his father’s work ethic.

Today, Schoenbaum, 79, is enjoying semi-retirement between his homes in Charleston, W.Va., and Sarasota, Fla. In addition to his role in Shoney’s affairs, he has business interests in realty, construction, insurance and, yes, bowling. He counts among his past business dealings a brief partnership in a professional football team with U.S. Senator Jay Rockefeller.

“That was quite an experience in my lifetime – being a partner with a Rockefeller,” Schoenbaum laughs. “We started out in 1965 as stockholders with the Charleston Rockets of the Continental Football League. We had quite a team.”

Of Rockefeller, Schoenbaum recalls, “He was as naive as anything you ever saw in your life when he first came to West Virginia. Here he is from a banking family. I never will forget when I was talking about add-on interest and he said ‘What’s that?’ I explained.”

With the extra time that retirement afforded, Schoenbaum found himself restless and embarked on a philanthropic mission to help various organizations.

The Sarasota Herald-Tribune noted recently that the first thing he did when he moved to Sarasota 20 years ago was strive to establish new levels of gift giving among the wealthy.

“It’s amazing how many people of substance, real wealth, don’t give a nickel to anything,” he was quoted as saying. “I know a lot of people who talk a lot but never do anything – but the bottom line is getting the job done.”

The article went on to say that charities who request money from Schoenbaum must make an accounting of themselves, and what they plan to do with his donation, before he gives a nickel, or a half-million dollars.

Over the years, he and Betty have donated money to numerous entities including $500,000 to the Ohio State Business School for scholarships; $500,000 to the Ohio State University School of Education for scholarships; $1 million to the Ohio State University Department of Athletics; $250,000 to the Salvation Army Territorial Development Fund; 5,000 shares of Shoney’s stock to Kiskiminetas Springs Prep School; $25,000 to the Women’s Resource Center in Sarasota, Fla.; $450,000 to the Betty and Alex Schoenbaum Human Services Center in Sarasota, Fla.; $700,000 to the Greater Kanawha Valley Foundation; $100,000 to the West Virginia Symphony Foundation; $500,000 to West Virginia University for scholarships; and they were instrumental in the $1 million grant to The Shoney’s Foundation, Inc. for scholarships to children of employees of Shoney’s lnc. In 1987, when approached by fellow restaurateur Jim Tweel of Huntington, Schoenbaum donated $50,000 to purchase a floating stage for Huntington’s Harris Riverfront Park.

In addition to donating his own money, Schoenbaum has been active in fundraising for the Boys and Girls Club, Junior Achievement, Boy Scouts, the Heart Association, a camp for children with asthma and Jewish affairs.

Schoenbaum is a man fiercely proud of his Jewish heritage. Included in his many donations are $600,000 for the Tel Mand Regional Library in Tel Mond, Israel; $350,000 to build a religious, cultural and social center at Temple Beth Shalom in Sarasota, Fla.; and $250,000 to B’nai Jacob Synagogue in Charleston. And for a man who most likely has dealt with prejudice in his lifetime, he shows no signs of bitterness or resentment. In fact, it was Alex Schoenbaum who first opened a restaurant to Blacks in Charleston.

Schoenbaum attributes much of his philanthropic work to former Ohio State football coach Woody Hayes.

“Woody Hayes had an expression – ‘You don’t give back, you give forward.’ And we feel like we ought to be a part of the future, not the past.”

Because of his accomplishments not only as a businessman, but as a humanitarian, he has received countless honors including a former Pioneer of the Year Award from Nation’s Restaurant News; member of the foundation board and steering committee of Ohio State University; Distinguished Service Award from Ohio State University; member of the Board of Trustees of the University of Charleston; Honorary Doctorate of Laws, University of Charleston; member of the Board of Trustees at Kiskiminetas Springs Prep School; National Advisory Board of the Salvation Army; chairman of the highest division in the United Way – the Alexis de Tocqueville Society; enrolled in the Prime Minister’s Club of the state of Israel; Human Relations Award from the American Jewish Committee; member of the Jewish Sports Hall of Fame; the Florida Senate Resolution for Philanthropy and Civic Leadership; the Philanthropic Donor of the Year award for the National Association of Fund Raising Executives, Southwest Florida chapter; and recipient of tribute by U.S. Senator Jay Rockefeller of West Virginia.

Schoenbaum credits such success to his ability to get along with people (much like his father) and “getting people to know me because of my name. I think my name helped me. I was pretty well known. Football and athletics had a lot to do with it. A lot of people have the exposure but don’t use it. I had the exposure and used it.

“I’ve always worked and tried to make a buck. Going back to the days when I said a nickel and a dime were important. I’ve made it important all my life. It’s still important.”

Prennis can vouch for that. “He finally bought a private jet a few years ago,” Prennis said. “And he has two pilots on call if he needs to be flown somewhere. But he won’t use the jet because he says it costs too much to run.”

Looking back on his life, Schoenbaum says his family is the one thing he is most proud of.

“My wife and I talk about it often – how lucky we are – we’ve got every reason to be pleased with our lives, our children’s lives and our whole family. In spite of being so busy most of my life, the family has turned out well. Of course, and this is hard for me to realize, we have also made it possible for a lot of families to enjoy the comforts of life and to be well-off financially because of Shoney’s. We have around 30,000 employees.”

In 1992, Schoenbaum returned to Huntington as part of “Shoney’s Founder’s Week” – a celebration of the national franchise’s West Virginia roots.

“A lot of people don’t know this, but West Virginia led the country in Shoney’s sales for many years,” he said while seated in one of the booths at the franchise’s U.S. Route 60 East restaurant. “Let me set the record straight. Shoney’s was born and bred in West Virginia. We want the world to know that this is where it started.”

• • •

Looking back on his Huntington roots, the gruff old Schoenbaum grows somewhat nostalgic.

“I enjoyed my days at Huntington High School and the circle of young people that I ran around with. They were so friendly. I really enjoyed life then. It was a real pleasant feeling.”

As for today, Schoenbaum asserts that Huntington must be more progressive and optimistic if it hopes to forge ahead.

“There’s too much negativity in Huntington. Yet I am surprised, still surprised, at how much they get done and I think they’ve done an excellent job in many areas – they ought to be proud of some of the things they’ve done at Marshall University, the new stadium, the beautiful streets and their willingness to try to do something with the waterfront.

“Eventually, it will work out. Something good will happen. If the people could just start thinking about what a great place it is. It has always been a beautiful city, still well laid out and still a beautiful place to live.

“And,” he notes with a smile, “they’ve got beautiful girls. Huntington has always been known for it.”