A look back at a time forgotten when picture show houses thrived throughout the region.

By Joseph Platania

HQ 25 | SUMMER 1996

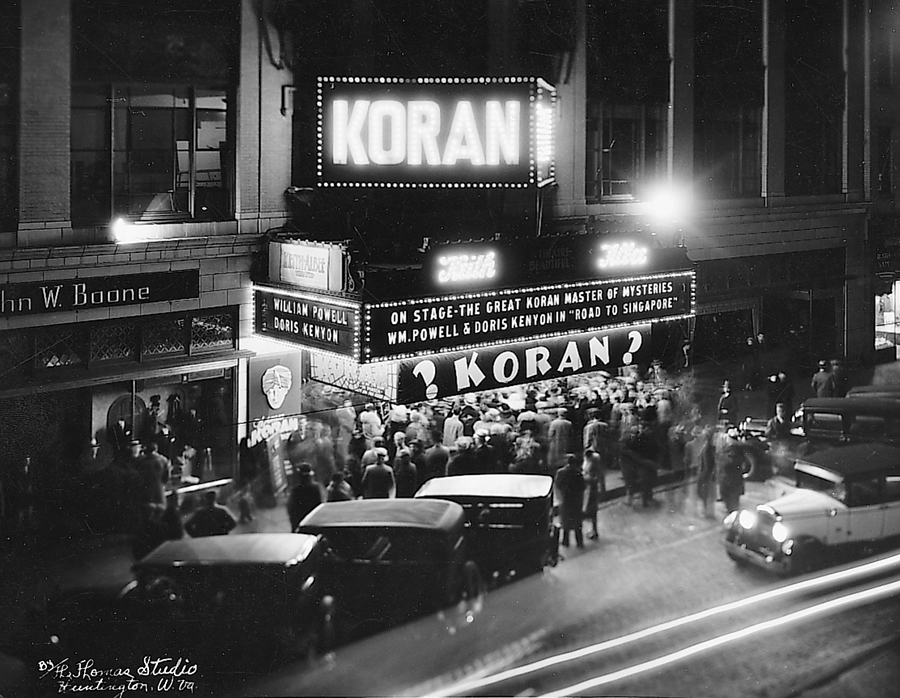

Since the early years of this century, Huntington’s downtown movie theaters have been showcases for the latest entertainment from Hollywood. From the opulent Keith-Albee to cozy neighborhood theaters, the Huntington area has had some 40 movie houses in operation since the first nickelodeon opened on Fourth Avenue in 1905.

The three remaining downtown theaters: The KeithAlbee, Camelot and Cinema along Fourth Avenue, once referred to as “theater row,” are city landmarks.

The Cinema, previously named the Orpheum, is the city’s oldest theater – it has continuously been in operation since March 1916, when the silent movie “Peggy” was the premiere showing. The theater then boasted a $10,000 musical instrument that “combined symphonic orchestra and cathedral organ sounds” to accompany the two-reelers. During the Cinema’s 1995 renovation from a single screen to a multiple-screen theater, a Lyric/Orpheum coupon book offering five-cent admissions was discovered – at one time a separate theater called the Lyric was also located on Fourth Avenue near Eighth Street. That theater closed around 1929.

The price of admission increased from 15 to 30 cents when motion pictures with sound were introduced. A “100 percent talking picture” policy began at the Orpheum in November 1928. Several weeks later, the Keith-Albee, which had opened down the street in May 1928, was equipped for “talkies.”

Another downtown theater, the Strand, resisted the new technology. A January 13, 1929, advertisement for the Strand read: “Realizing that sound and talking pictures are not being accepted generally by the people of Huntington and being anxious to please our patrons, sound and talking pictures have been discontinued.” Instead, the theater restored its orchestra with “real live artists.”

Before there were movie theaters, many cities and towns across America had an opera house. Huntington’s first opera house, The Harvey Opera House, was built in the early 1870s on the northwest corner of Third Avenue and 10th Street, states George S. Wallace in his Cabell County Annals and Families. Wallace adds that inside the opera house, lighting was supplied by oil lamps and was all on one level with some seats raised in the back as a “peanut gallery.” The building was destroyed by fire in 1879.

It was not until six years later that the city’s next show place was built by a Virginia pharmacist named Ben T. Davis. Davis arrived in Huntington from Virginia by way of stagecoach and train in 1871, the year of the city’s founding, writes Wallace. He states that Davis bought a lot on the southeast corner of Eighth Street and Third Avenue (now the home of Bazaar Home Fashions) and erected the Davis Opera House, adding that the pharmacist had his drug store on the ground floor.

A local historian writes: “In 1884, Huntington was 13 years old and a booming ‘metropolis’ of 4,000 people.”

The Davis Opera House, completed in 1885 at a cost of $35,000, seated 800. In 1892, the building was remodeled and the name changed to the Huntington Theater. The remodeled theater was 60 feet by 160 feet with a stage that was 40 feet by 60 feet. It seated 1,400 people. During the following years, the Huntington Theater changed hands several times before it was eventually purchased in 1915 by brothers Abe and Sol Hyman.

With the release of the first full-length motion picture, “The Train Robbery,” a western, in 1903, a new age began. Many of the new movie theaters that sprang up were called “nickelodeons” because the price of admission to see the new two-reel silent films was a nickel.

Abe “A.B.” Hyman and his brother, Sol, were Huntington’s first theater entrepreneurs. Born in Baltimore, Md., they later moved with their parents to Pocahontas, Va., where their father was a merchant. Following their father’s death, Abe, then a young man, became head of the family of nine. According to Derek Hyman, Abe’s grandson and president of the Greater Huntington Theater Corporation, the family sold some property to a coal company and headed west by train. When they reached Huntington, they decided to settle in the young city.

Derek Hyman says that in 1907, Abe and Sol went into the tavern business. By 1909 the two owned the Palace Saloon at 328 9th Street. Derek adds that the Hyman brothers put in a nickelodeon in the saloon to show the new two-reelers, and this launched their career in the theater business. Later, they also went into real estate development and had a coal and tubing company.

Wallace writes that Huntington’s first “movie theater” was called the Dreamland, and it opened in 1905 in a building on the southwest corner of Fourth Avenue and Ninth Street. The site later became the Farr Hotel and then the Governor Cabell Hotel. At about this same time, a second movie theater, the Wonderland, opened on Third Avenue, says Wallace, adding that these two theaters were soon followed by “small houses” such as White City on Ninth Street, Fairyland on Third Avenue between Eighth and Ninth Streets and, in 1908, the Gem in the 900 block of Third Avenue. Names of other early movie houses include the VanDorn in 1906, Penny Arcade, Grand and the Lyceum in Guyandotte. The 1907 city directory lists a total of six theaters in town.

In 1910, an old skating rink in the 800 block of Fourth Avenue was purchased and converted into a movie theater named the Lyric.

Local resident Tony Rutherford, a movie memorabilia collector, recalls that the Lyric opened December 24, 1910, and billed itself as “the first theater to open south of Third Avenue.”

Wallace states that several years later, the Lyric was purchased by the Hyman brothers and remodeled. The theater was a successful venture for the Hymans and, later, they opened the Dixie Theater, almost directly across Fourth Avenue from the Lyric.

The Elk, which opened in 1911 in the 1000 block of Fourth Avenue, “across from the Elk Temple” according to an advertisement, was another early theater. Rutherford adds that the Elk, later the Sans Souci, advertised itself as “the most fireproof theater in the city, with 10 exits.”

The It, which opened in 1910 on Third Avenue near 20th Street, was the first neighborhood theater outside of Guyandotte. An advertisement for the It boasted that the theater “was thoroughly disinfected on a daily basis.” The It later became the Park, which was in business for many years.

Other early downtown theaters (nickelodeons) were the Royal, which opened in 1911, and the Placade, which opened on the north side of Fourth Avenue near 11th Street in 1913.

Around 1909, a theater named the Hippodrome opened on Third Avenue near 11th Street. Both the Placade and the Hippodrome were vaudeville houses. The Hippodrome later was the site of the State Theater.

The Strand was another vaudeville theater. Rutherford states that the Strand was located in the 800 block of Fourth Avenue, and it later became the Roxy Theater. The Strand is notable for its decision in January 1929 to discontinue showing motion pictures with sound. Several months later, the Strand went out of business.

In March 1916, the Orpheum, now the Cinema, opened in the 1000 block of Fourth Avenue. Other popular venues for two-reelers were the Colonial Theater at 914 4th Avenue and the Victor at 1900 8th Avenue.

The following year, the People’s Theater opened in Guyandotte.

During its career as a vaudeville theater, the Hippodrome was acquired by the Hyman brothers who later purchased the Orpheum. The 1918 city directory lists specifically the Huntington Theater and the New Hipp, formerly the Hippodrome, as vaudeville theaters.

The early 1920s saw the opening of new neighborhood theaters such as the Iola on 14th Street West, the Margaret at 20th Street and Eighth Avenue, the Mecca in Guyandotte and People’s in Ceredo.

In 1924, the Shriver opened in Guyandotte and the State opened at 1048 4th Avenue downtown. During this period, vaudeville shows continued to entertain audiences at the Huntington, It, Orpheum and Grand.

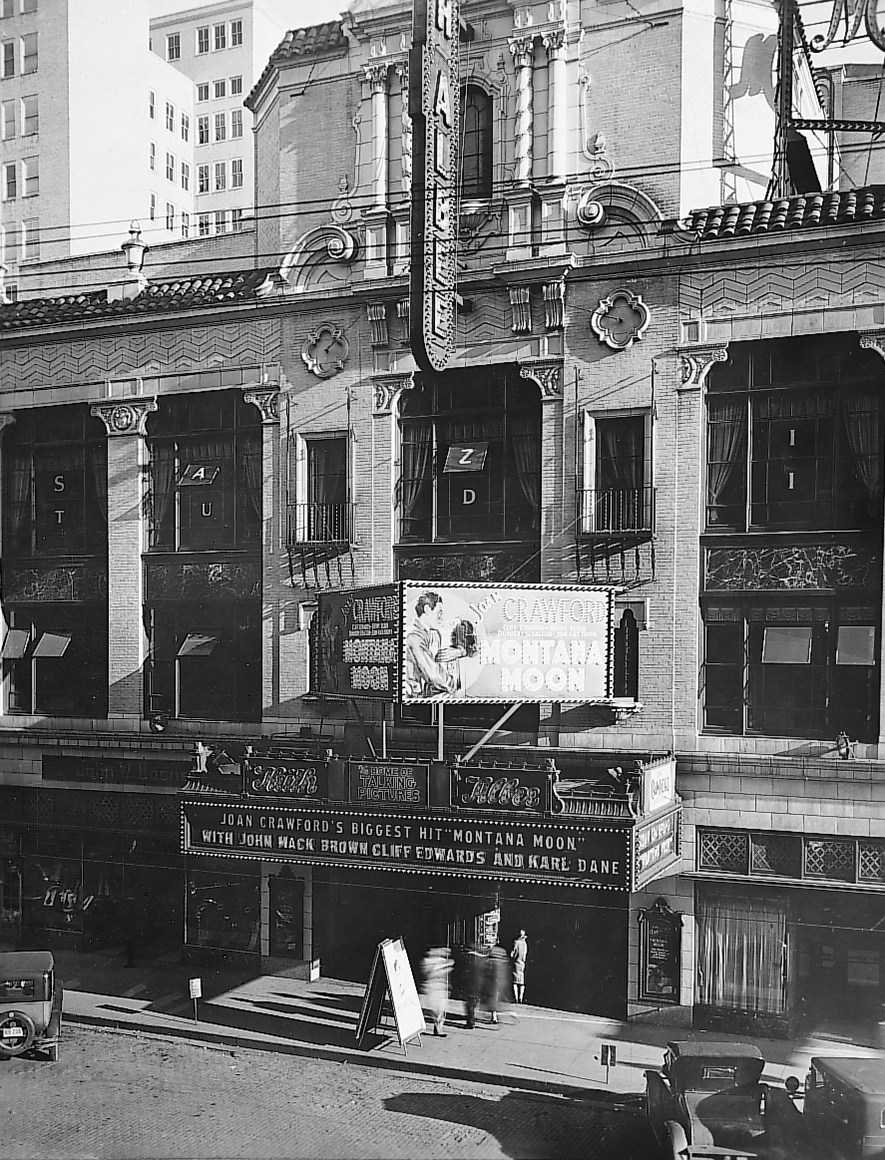

Wallace states that on November 15, 1926, the newly built Palace Theater, now the Camelot, began operation with combination stage and screen shows. But the release of the first talking picture, “The Jazz Singer,” in 192 7, spelled the end of vaudeville and silent movies.

In May 1928, the Keith-Albee, one of the nation’s largest motion picture theaters outside of New York City, opened with Abe Hyman as president. Wallace reports that the new Keith-Albee was an air-conditioned theater with a seating capacity of 3,000, divided with 1,800 on the lower floor, 1,000 in the balcony and 200 loge seats.

Built during an age when movie theaters were more like movie palaces, the Keith-Albee was, and still is, West Virginia’s largest and most ornate theater. In fact, there is nothing like it within 150 miles of Huntington.

The “Keith” is the creation of celebrated architect Thomas Lamb, who designed some of the most opulent theaters in Europe and in North and South America.

When Abe Hyman decided to build a new showplace for vaudeville and movies in downtown Huntington in the 1920s, he wrote Lamb asking if he would design the theater.

Derek Hyman explained that Lamb agreed to design the theater beginning with the basement and working up. By the time they had completed the basement, the initial $250,000 that they raised had been exhausted, said Hyman, adding that “it ended up costing them a few million more.”

Records show that more than 550 tons of steel and two million bricks were used in the Keith-Albee’s construction, which took 14 months to complete.

At its center was a 3,000-seat main auditorium with superb acoustics, a fully rigged stage, and four floors of adjacent dressing rooms. Trapdoors on the stage enabled animals, performers and equipment to rise to the stage or be lowered into a large room below.

The auditorium’s rounded ceiling, three floors above the stage, was painted blue to make it appear as if the roof had been removed to reveal the open sky. Small lights in the ceiling gave the impression of twinkling stars in the night sky.

A mezzanine under the balcony extends the length of the building. It overlooks the three-story main lobby with its semi-circular ceiling, accented with three huge stained glass chandeliers. The entire theater was decorated in the highly-ornamental rococo style popular in the 20s.

The Keith-Albee took its name from the popular vaudeville circuit of the time. Ironically, the release of the first talking picture sounded the death knell for vaudeville. The once popular form of entertainment was all but dead within several years of the Keith-Albee’s opening.

During the Great Depression, many Americans tried to escape, if only briefly, hard economic times by going to the movies.

In the 30s, there were a dozen movie theaters in the Huntington area from the Dixie in Guyandotte to the People’s in Ceredo and the Strand in Kenova.

Along “theater row” (Fourth Avenue between Eighth and 11th Streets), there were five theaters: State, Orpheum, Palace, Keith-Albee and Roxy. One block over, there was the Rialto at 1023 3rd Avenue.

Tony Rutherford states that the Margaret, on Eighth Avenue at 20th Street, advertised that it was the only theater open during the 1937 flood. “If you want to see a movie, come to the Margaret,” said its ad.

In 1938, the Abbott was built on 14th Street West near Washington Avenue. Originally built for low-budget films, it was later transformed into a performance-type theater with a large stage.

For years, the Abbott was home to the now-defunct Community Players. According to Lorena P. Shank, president of the revived board of Community Players, the Abbott was named for P.E. Abbott who for many years owned and operated a picture framing business in the west end.

Around 1940, the Beverly, a popular 500-seat theater, opened at the intersection of Washington Boulevard and Norway Avenue.

The 1943 city directory lists 14 movie theaters in operation including neighborhood theaters from Guyandotte to Kenova. Some of their names were the Mecca in Guyandotte, Fox at 1630 8th Avenue, Uptown at 1950 8th Avenue, Westmore at 1317 Adams Avenue and Park (formerly the It) at 2016-18 3rd Avenue.

The May 1995 issue of Life, which was devoted to the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, states that in 1945, “for 30 cents you got a double feature with a cartoon and a cliff-hanger (serial movie) thrown in. No wonder 98 million Americans went to the movies each week.”

Derek Hyman explains that after first-run movies played a week or two at a downtown theater, they would go to the neighborhood theaters for a “second run.” Neighborhood theaters also had the serial movies that kept you coming back week after week.

On March 15, 1947, the Tipton Theater, located on the north side of Fourth Avenue and Eighth Street, opened. Billed as “Huntington’s newest major theater,” the 1,500-seat Tipton was built by Abe and Sol Hyman.

The Tipton “was named in honor of the late Cecil Tipton, a business associate of the Hyman brothers of more than 25 years,” states a report in The Herald-Dispatch. The Tipton was located on the site of the former Lyric Theater. According to early city directories, C.E. Tipton is listed as manager of the Lyric.

On October 22, 1950, “a fire completely destroyed the Tipton,” states a newspaper account.

The advent of the age of television and the installation of TV sets in millions of American homes in the late 40s and early 50s signaled the beginning of major changes in the motion picture industry.

During the 50s and 60s, theaters were equipped with wide screens and stereophonic sound as well as equipment to show the Cinemascope, 3-D and VistaVision movies that Hollywood was turning out.

In the car-mad 50s, drive-ins flourished. There were drive-in restaurants, churches, motels, banks – even funeral parlors. In 1958, the drive-in movie craze peaked with 4,063 screens nationwide.

According to a newspaper account, the first drive-in movie in the Huntington area opened in August 1951. The East Drive-In Theater was located on U.S. Route 60, just east of the city limits. The 1952-53 city directory also lists the Ceredo DriveIn Theater at Ceredo, WVa.

The Greater Huntington Theater Corporation, started by Abe and Sol Hyman in the mid-l 920s, eventually controlled most of the theaters in the region including the downtown theaters and the Park Place Cinema 7 in Charleston, a theater complex with seven screens. The corporation also owned the East Drive-In, the Starlite Drive-In in Lawrence County, Ohio, and the Ceredo Drive-In.

During the late 50s and into the 60s, neighborhood theaters began to close. By 1960 the number of Huntington theaters was down to seven including drive-ins.

As recently as 1960, “Blacks couldn’t attend movies in Huntington unless they came in a side or back entrance and sat in the balcony,” a local resident recalled in a July 1978 newspaper article. Eventually, the Civil Rights laws of the mid-60s integrated all public theaters in America.

Dr. Ancella R. Bickley in her book Honoring Our Past: Proceedings From the Two Conferences in West Virginia’s Black History, published in 1991, states that (in Huntington) “A small all-black movie house operated on Eighth Avenue above 16th Street.”

The booklet from the 1993 reunion of graduates of the former all-black Douglass High School contains a list of black-owned businesses in Huntington in 1921. Included is the Dreamland Theater at 1620-22 8th Avenue, owned by A.C. Colvin. A review of city directories from 1918 into the 1950s finds that there were small, all-black movie theaters with names such as the Valentine, Olden, Dreamland, Fox, Lincoln and Carver on Eighth Avenue between 16th Street and 20th Street in the city’s African-American community.

About 1970, the Beverly Theater in the southeast part of town closed. During the late 70s and early 80s, drive-in theaters also began to close.

The 1980 city directory lists seven theaters including the Abbott and the Stage Door at 821 10th Avenue. A new phenomenon in the early 1980s was the rise of multiplex theaters in shopping malls. This major change in theater design soon spread to downtown theaters. In the mid-70s, the lower section of the main theater of the Keith-Albee was divided into one 650-seat theater and two 225-seat theaters. A fourth theater was later added behind the concession counter.

Hyman explains that screens were added in the downtown theaters in order to accommodate all of the movies being released by Hollywood. Prior to this, the downtown theaters were missing out on about 20 percent of the movies being released.

Huntington’s list of theaters again decreased in 1993 as the East, the region’s last drive-in theater, failed to reopen for the summer.

In 1995, the Cinema, the last single screen theater in downtown, was remodeled into a multiple-screen theater bringing the total number of screens in downtown to ten.

• • •

Looking back at most of this century, the Huntington area has had dozens of movie theaters in operation. Some were open only a few years. Many were open during the Golden Age of motion pictures in America, and a few have been in business for more than 60 years and continue to attract the movie-going public.

Although the era of movie palaces has passed, the remaining downtown theaters are attractive, well-maintained and popular with today’s movie-goers.

Even in this age of VCRs and cyberspace, watching a movie on the big screen with an audience in a darkened theater especially designed for that purpose generates its own special kind of magic.