By James E. Casto

HQ 58 | SUMMER 2006

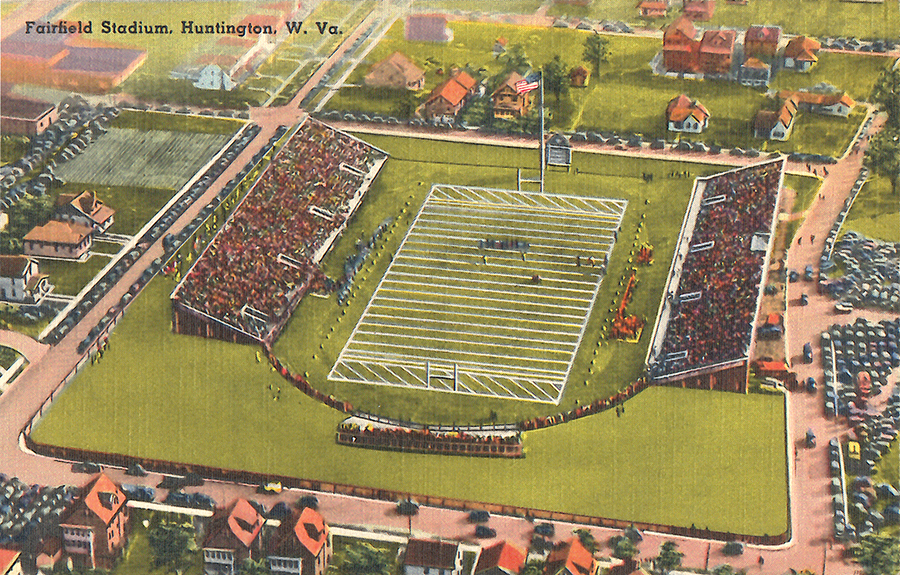

When film crews were in Huntington in April shooting scenes for We Are Marshall, the new movie chronicling the inspiring aftermath of the 1970 Marshall University plane crash, they filmed at a number of campus and community settings. But when it came time to film crucial scenes set at Fairfield Stadium, they had to look elsewhere for a stand-in. Today Fairfield is only a memory.

The moviemakers eventually ended up shooting the We Are Marshall game scenes at a stadium in the Atlanta, Georgia, area.

These days, of course, Marshall plays football at its handsome Joan C. Edwards Stadium, but for more than 60 years — from 1928 to 1990 — Fairfield was the home of the Herd. At the same time, the red brick stadium on Huntington’s South Side was the site of countless high school football games and a variety of community events.

It’s been years since the last football game was played at Fairfield. The old stadium’s badly deteriorated eastside stands were demolished years ago as a safety hazard. And in the spring of 2005 the stadium’s remaining elements were demolished to make way for the Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine’s new $22.5 million Clinical Education & Outreach Center. Now under construction, the center is scheduled for completion late this year or in early 2007.

The history of Fairfield Stadium can be traced back to the West Virginia Legislature’s 1925 creation of the Huntington Board of Park Commissioners. One provision of the park board’s charter empowered it to join with what was then Marshall College and/or with the City of Huntington and the Cabell County Board of Education to build a stadium.

Perhaps not surprisingly, there was disagreement about a suitable site. Marshall wanted to locate the stadium either on campus or adjacent to it. The Huntington Chamber of Commerce argued that League Park in West Huntington would be a better choice. But from the first, the park board had its eye on a piece of South Side property about a half-dozen blocks from the Marshall campus — a tract of land located between Charleston and Columbia avenues, and 14th and 15th streets. Eventually the park board bought the land from Huntington businessman W.N. Prindle, paying him $25,000 for it.

More disagreements followed about how best to go about constructing and operating the stadium, but finally the park board, Marshall and the school board ironed out a three-way agreement and construction of the 10,000-seat stadium began. Its final price tag, after the inevitable cost overruns, was $130,000.

When discussion turned to selecting a name for the new stadium, George S. Wallace, the park board’s long-time president, jokingly proposed “Cockroach Commons” — referring to the property’s former use as a garbage dump.

On a more serious note, Prindle suggested that the stadium be named Fairfield, after his home county of Fairfield in Ohio. And his idea prevailed.

Huntington High School played the first game in the new stadium, defeating Portsmouth (Ohio) High School 18-0, on Sept. 29, 1928. Marshall didn’t play its first game at Fairfield until the following Oct. 9, when it teamed up with Huntington High for a doubleheader and the stadium’s official dedication. Huntington defeated Logan 21-0, and then Marshall made it a double whitewash by routing Fairmont State 27-0.

Over the years, Fairfield would be home field for football teams from Huntington High, Huntington East High and Douglass High, the county’s pre-integration black school. Today, all three of those old schools are closed, and the Huntington High Highlanders play on a field at the school’s Route 10 campus.

During its heyday, Fairfield hosted many events other than football, including the annual West Virginia High School Band Festival and, in 1959, an outdoor pageant celebrating Cabell County’s 150th anniversary. In 1964, when famed evangelist Billy Graham came to Huntington, Fairfield was the only place in town big enough to hold the crowd.

Marshall played its last football game at Fairfield on Nov. 10, 1990, losing 15-12 to Eastern Kentucky University. In departing Fairfield, the Herd left behind one of the poorest excuses for a stadium found anywhere in college football, but the school also left behind some splendid memories.

Surely none of those memories shines brighter than Marshall’s Sept. 25, 1971, game with Xavier. In the wake of the plane crash, many urged that the school abandon football. Instead, the school patched together a team that sportswriters and fans christened “The Young Thundering Herd.” The Xavier game was the second game of the 1971 season and Marshall’s home opener.

Marshall took the field a three-touchdown underdog but miraculously managed to upset Xavier 15-13. As Marshall Coach Jack Lengyel proclaimed afterwards, “No one thought we had a chance to win except the team.” An hour and a half after game’s end, the Fairfield stands were still full as the crowd continued celebrating. Needless to say, the Xavier game will be a highlight of the new Marshall movie.

From the outset, the three-way ownership of Fairfield never worked well. With nobody solely in charge, maintenance was often neglected and the stadium was allowed to badly deteriorate. In 1962, the situation became so dire that city building inspectors slapped a CONDEMNED sign on the stadium, declaring it unsafe for use. Modest repairs were made to keep the stadium open, but it was clear more had to be done.

Marshall voiced a willingness to dramatically upgrade Fairfield but only if it became sole owner. In 1970, the school system and the park board surrendered their shared ownership. Marshall then installed an Astroturf playing surface, built new dressing rooms and made room for 6,800 more seats by lowering the playing field.

After Marshall left for its new stadium, Fairfield saw little use. The dressing rooms were remodeled to house Marshall’s Forensic Science Center, and nearby Cabell Huntington Hospital began using the old playing field for an overflow parking lot.

Then came the decision to use the Fairfield site for the med school’s new Clinical Education and Outreach Center, and soon the wrecking crews began work on what was left of the venerable old stadium.

Fairfield may be gone, but it’s by no means forgotten. Plans call for the new med school building to include a suitable memorial remembering the stadium, the teams that played there and the loyal fans who cheered them on.