Two local war heroes who served their nation with valor

By James E. Casto

HQ 80 | WINTER 2013

West Virginians have never hesitated to answer their country’s call to arms. While their homes were still part of Virginia, brave men from the western mountains fought in the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, the War of 1812 and the Mexican War. At least 40,000 men from western Virginia – some in Union blue and others in Confederate gray – fought in the bloody Civil War that gave birth to the new state of West Virginia. Each conflict since has seen West Virginians do their part – and more.

More than 230,000 West Virginians donned their country’s uniform in World War II. From the deadly skies over Nazi Germany to the bloody beaches of Normandy and Iwo Jima, fighting men from the Huntington area served with valor during those danger-filled days. This, the second part of a two-part article, profiles two of WWII’s bravest of the brave – Justice M. Chambers and Walter C. Wetzel.

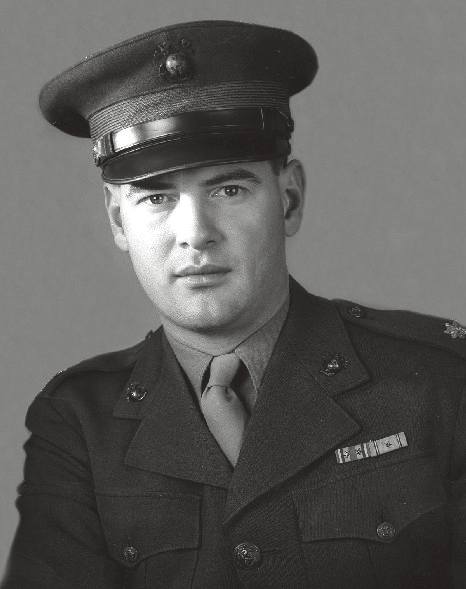

Justice M. Chambers

The name “Iwo Jima” is written large in the history of the U.S. Marine Corps.

In February 1945, more than 4,500 Marines were killed in the bloody battle to take the Japanese-held island. Thousands more were wounded. Bravery was the order of the day. More Medals of Honor were earned at Iwo Jima than in any other Marine battle, before or since. Twenty-four men received the medal for their valor on Iwo.

One of those men was Justice M. Chambers of Huntington’s Westmoreland neighborhood.

Today, the bridge that carries Adams Avenue into Wayne County is marked with green signs that identify it as the “Colonel Justice M. Chambers Memorial Bridge.” His boyhood home is a short walk from the green sign at the Wayne County end of the bridge.

Arthur Chambers, a furniture salesman, and his wife Dixie had two girls and a boy. Justice, the middle child, was born in 1908. A boyhood bout with polio left him with one leg shorter than the other. The men he would later lead into battle would call him “Jumping Joe,” because of the way he ran to compensate for his shortened leg.

Graduating from Huntington High School, Chambers worked his way through three years at Marshall University, and then transferred to George Washington University. From there he want on to National University to earn a law degree.

He joined the peacetime Naval Reserve in 1929. Later he transferred to the Marine Corps as a private and steadily rose in the ranks. When his unit was called to active duty in 1940, he was a captain. He showed what he was made of early in his Marine career. He served initially in Edson’s Raiders, a commando unit, where he won the Silver Star for evacuating wounded men and directing a night defense of an aid station on the island of Tulagi. He did so even though wounded himself.

Promoted, Lt. Col. Chambers led his men in the attacks on Saipan, where he suffered a blast concussion, and Tinian. Then came Iwo. It would be his fifth island assault. From the outset of the battle, he was in the front line, encouraging his men to advance and repeatedly braving enemy fire himself – until he was hit by a machine gun burst. A bullet hit him in the left collarbone, passed through his chest and his lung, and exited his back. He was removed to an aid station, then to a hospital ship for surgery.

The recommendation that Chambers be awarded the Medal of Honor began to work its way up the chain of command immediately after Iwo fell but it would be five years before President Truman hung the medal around his neck in a brief ceremony on Nov. 1, 1950. By this time, Col. Chambers had retired from the Marine Corps because of his war wounds and was working as a staff adviser to the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee.

His Medal of Honor citation read in part:

Exposed to relentless fire, he coolly reorganized his battle-weary men, inspiring them to heroic efforts by his own valor and leading them in an attack on the critical, impregnable high ground. … He was directing the fire of the rocket platoon when he fell, critically wounded.

After the presentation, Chambers spoke briefly. His daughter Pat recalled, many years later, her father saying something like “This is for my men.”

Chambers went on to serve as Deputy Director of Civil Defense for Truman. When President Eisenhower was elected, he left government service and turned to lobbying. Later, President Kennedy appointed him Deputy Director of the Office of Emergency Planning.

He died July 29, 1982, at age 74 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. In 2011, Terence W. Barrett, a licensed psychologist at North Dakota State University in Fargo, published The Search for the Forgotten Thirty-Four, a book in which he cited 34 men who been honored by the Marine Corps but were unheralded in their hometowns. He included Chambers among the 34. (Some of the information in his article is taken from Barrett’s book, with his permission.)

It’s true that Justice Chambers mostly slipped from the public eye in Huntington after his 1950 medal ceremony, but recent measures have done much to redress that oversight.

Another Marine who won the Medal of Honor on Iwo, Hershel W. “Woody” Williams of Ona, and his fellow members of Huntington Detachment 340 of the Marine Corps League have done much to gain Chambers the local recognition he deserves. In 2002, they successfully lobbied Wayne County officials to install a courthouse plaque that memorializes Chambers. In 2004, they convinced the West Virginia Legislature to rename the Auburn Road bridge in the Marine hero’s honor. And this year saw Chambers inducted into the Greater Huntington Wall of Fame.

Walter C. Wetzel

Two states – West Virginia and Michigan – claim Medal of Honor recipient Walter C. Wetzel, who was awarded the medal posthumously in 1946.

Born in Huntington in 1919, Wetzel was a young man living in Roseville, Michigan, in July of 1941 when he joined the Army. Today, a state park in Macomb County, Michigan, is named in Wetzel’s honor, as is an elementary school for U.S. military and civilian personnel in Baumholder, Germany.

On April 3, 1945, Wetzel was a private first class in the 13th Infantry Regiment, attached to the 8th Infantry Division. The long history of the 13th Infantry dated back to the late 1700s but the regiment had been disbanded. In 1940, with war clouds gathering in Europe and Asia, the unit was reconstituted at Fort Jackson, South Carolina.

In July 1944, the regiment found itself fighting through the hedgerows of France, and then it moved into Germany as the Nazi army retreated before the American advance.

Wetzel’s official Medal of Honor citation reads:

Pfc. Wetzel, an acting squad leader with the Anti-Tank Company of the 13th Infantry, was guarding his platoon’s command post in a house at Birken, Germany, during the early morning hours of 3 April 1945, when he detected strong enemy forces moving in to attack. He ran into the house, alerted the occupants and immediately began defending the post against heavy automatic weapons fire coming from the hostile troops. Under cover of darkness the Germans forced their way close to the building where they hurled grenades, 2 of which landed in the room where Pfc. Wetzel and the others had taken up firing positions. Shouting a warning to his fellow soldiers, Pfc. Wetzel threw himself on the grenades and, as they exploded, absorbed their entire blast, suffering wounds from which he died. The supreme gallantry of Pfc. Wetzel saved his comrades from death or serious injury and made it possible for them to continue the defense of the command post and break the power of a dangerous local counterthrust by the enemy. His unhesitating sacrifice of his life was in keeping with the U.S. Army’s highest traditions of bravery and heroism.”

In an Internet posting, Tom Bolick, the son of Leo Bolick, a 13th Infantry veteran, says his late father always claimed the official account of that day was wrong on several counts because it was “written by an officer who was not there at the time.”

Leo Bolick should know, as he had been Wetzel’s platoon sergeant since early in 1943 at Fort Jackson and was one of the men whose lives Wetzel saved that day.

The sergeant recalled that before joining the Army Wetzel had worked in Detroit, mounting tires in an auto plant. “He had very strong stomach muscles and would let anyone in the company hit him in the stomach as hard as they could without hurting him.”

Here’s how Wetzel was killed, as Leo Bolick’s son realled his father’s account:

“On the morning of April 3, 1945, before dawn, my father was leading a patrol down the narrow street in the village of Birken, Germany, when a small group of German soldiers fired on them with automatic weapons. The patrol ran into houses and started returning fire. There were several men in the house with my father and Wetzel. A grenade was thrown in the window, someone yelled ‘grenade,’ everybody fell to the floor. Wetzel fell on the grenade, blowing up in his stomach area, and saved the rest of the men in the room. A few minutes later the Germans stopped firing and then retreated from the town. Wetzel was still conscious and lived for several minutes after he was wounded. He would pray for a moment, then he would cuss for a while. The last thing Wetzel said was ‘Sarge, I think the goddam son of a bitches have killed me,’ and he died.”

Leo Bolick said Wetzel was “the last man in the platoon to be killed” in the war. He is buried in the Netherlands American Cemetery at Margraten in the Netherlands.

Tom Bolick says he took his father back to Birken in 1990. They looked for the house the unit was in the day Wetzel was killed but could not find it. “We did get to the cemetery to visit Wetzel’s grave. It’s the only time I ever saw my father cry.”

Undaunted Courage [Part 1]

In case you missed the first part of this two-part article, here are the three local World War II heroes who were profiled in it:

Robert Femoyer, a B-17 navigator was was mortally wounded on a bombing mission over Germany. Despite great pain and loss of blood, he refused injection of a sedative until he had directed the plane out of danger. He died shortly after being removed from the returned aircraft. He received the Medal of Honor in recognition of his heroism and self-sacrifice.

Carwood Lipton, a member of the 101st Airborne Division’s Easy Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, whose exploits became the stuff of legend. Historian Stephen Ambrose interviewed the unit’s members and wrote about them in his best-selling book Band of Brothers, which later became a hit HBO miniseries.

Hershel W. “Woody” Williams, who received the Medal of Honor for using a series of flamethrowers to knock out seven Japanese pillboxes on Iwo Jima, which had Williams and his fellow Marines pinned down under a murderous crossfire.