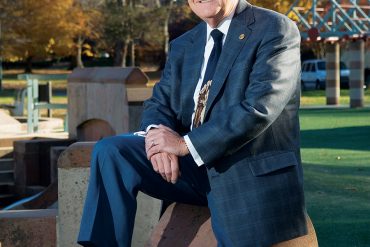

Hershel “Woody” Williams received America’s highest award for valor when he stormed the beach at Iwo Jima. Today at age 96, he is the sole surviving Marine from World War II to wear the Medal of Honor.

By James E. Casto

HQ 108 | WINTER 2020

In the closing days of World War II, Hershel Woodrow Williams, a farm boy from West Virginia, was awarded the nation’s highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor, for the gallantry he displayed during the bloody battle for the Japanese-held island of Iwo Jima.

Over the decades since, Williams — known affectionately to his family and many friends as Woody — has earned a chorus of thanks for his tireless efforts on behalf of the nation’s military veterans and their families.

On meeting Williams, one might easily mistake him for somebody in his 60s. In fact, on Oct. 2, 2019, he celebrated his 96th birthday. Ask him how he remains so spry and he credits clean living — and the daily exercise routine that was drilled into him as a young member of the U.S. Marine Corps.

Williams, the youngest of 11 children, was born and raised on a dairy farm. Every day his family would load up milk and other farm products and take them into nearby Fairmont, West Virginia, to peddle door to door.

“This was the Great Depression and times were mighty tough,” says Williams. “One of my brothers joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, and, returning home from his CCC camp, he showed me some dollar bills he had earned there. I decided I wanted to earn some of those dollars, so I joined. I was 16 years old.”

Before long, Williams was working at a CCC camp in Montana. “They paid us $21 a month and that was good money then,” he says with a laugh.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Williams returned home, determined to join the Marines. Because he was only 17, his parents had to sign their permission. His father had died in 1934, and his mother refused to sign her permission. So, he had to wait until he turned 18.

As soon as he did, he tried to enlist. “No way,” the Marines told him. All Marine recruits had to be at least 5 feet, 8 inches tall. No matter how straight and tall he attempted to stand, Williams couldn’t top 5 feet, 6 inches. But he didn’t give up. He just waited. The war continued, and in 1943 the Marine Corps, badly in need of recruits, sharply reduced its height requirement. He went back to the recruiting office and this time was accepted.

Because so many men were joining the Marines, Williams had to wait several months before being ordered to report to boot camp for basic training. Needing money while he waited, he asked the manager of the local taxi company for a job. With many of his regular drivers now in the military, the manager was desperate. Even though Williams was legally too young to be a taxi driver, the manager put him to work.

At the taxi company, part of his job was to deliver Western Union telegrams to people informing them that a loved one had been killed in the war. That experience would stick with him for a lifetime.

Once he completed his basic training, Williams joined other Marines as part of the U.S. island-hopping campaign aimed at rolling back Japan’s success in the Pacific.

Williams served at New Caledonia, Guadalcanal and Guam. Then, in February of 1945, he was part of the huge invasion force that stormed the Japanese stronghold of Iwo Jima. The battle for the island fortress was one of World War II’s bloodiest, and it was there that Williams’ actions earned him the Medal of Honor – America’s highest and most prestigious award for courage under fire.

“We were determined to capture Iwo Jima,” says Williams. “It was only about 600 miles from Japan and it had an airfield. Our B-29s were flying from Guam and Saipan and Tinian to bomb Japan, but if they ran out of fuel, had engine trouble or were damaged by Japanese fighters they had no place to land. Between when we secured Iwo Jima in March and the end of the war in September, our B-29s made 2,500 landings on the island.”

Just as the U.S. was determined to capture the island, Japan was equally determined to hold onto it, and so dug an elaborate system of underground tunnels and manmade hillside caves, guarded by machine guns tucked into more than 1,000 reinforced concrete pillboxes.

Bombing and shelling the island for two months did little damage to the entrenched Japanese troops. When the Marines charged ashore from their landing craft, their advance was stalled by withering fire from the Japanese. An officer asked for a volunteer to try taking out one or more of the several pillboxes that had his men penned down.

“I’ll see what I can do,” Williams said. At least that’s what others who were there recall. Williams himself doesn’t remember. “Much of this stuff is like a dream,” he says. “You wonder if it really happened. And yet some moments are still vivid. It’s almost like looking at a slow-motion movie.”

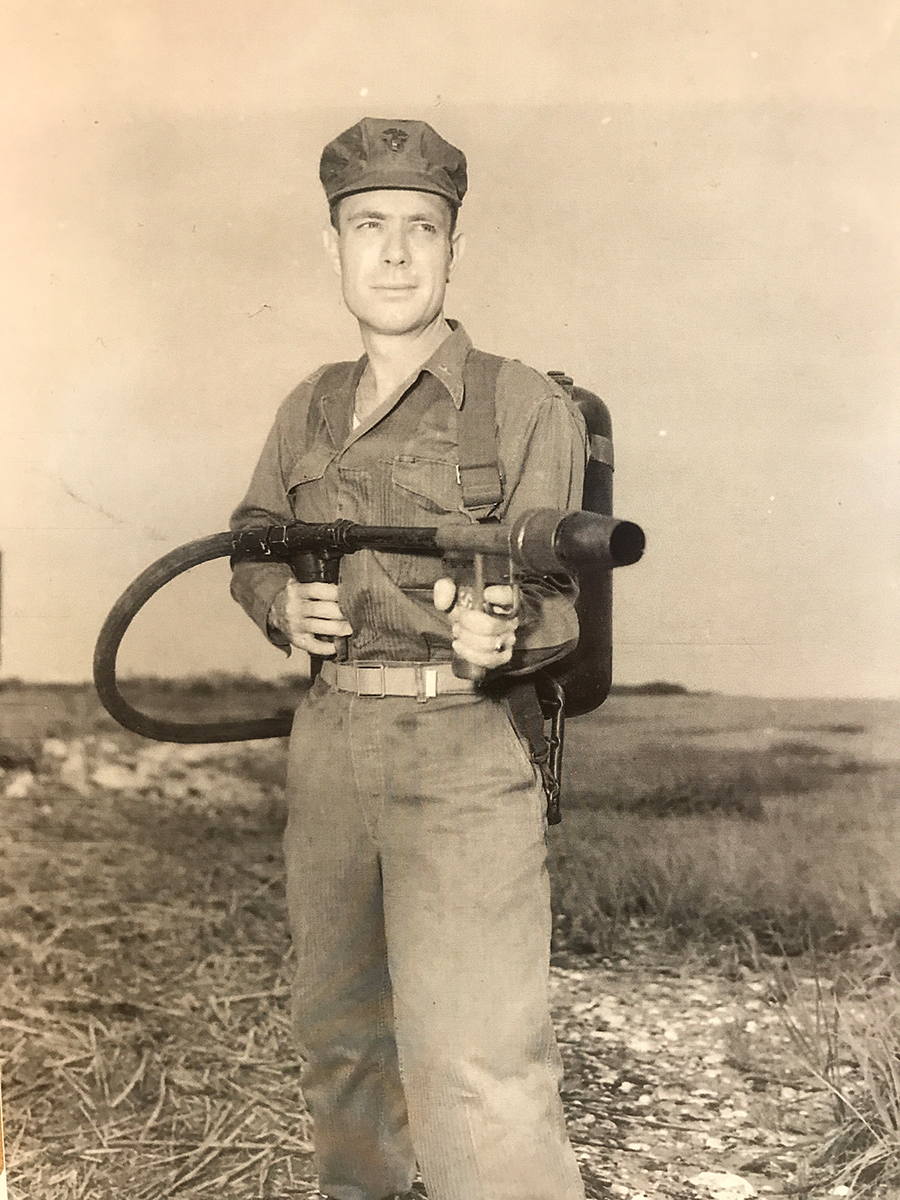

Strapping a heavy flamethrower on his back, Williams crawled toward the pillboxes. Once he was close enough, he pulled the trigger and a river of flame raced across the ground and into the gun port of the pillbox, incinerating the Japanese inside. Again and again Williams repeated the process, ignoring the danger involved. Bullets bounced off the tank of jellied gasoline on his back. Any one of them could have exploded the tank, enveloping him in flames.

“I remember the Japanese charging out of one of the pillboxes toward me,” he says. “I saw bodies, rifles and bayonets. I opened up on ’em. They quit coming.”

All this occurred on the same day as the famous American flag raising on Mount Suribachi. Williams says he was about a thousand yards away from the volcano and didn’t see the flag at first. “I saw it immediately after it was up, and the reason was Marines around me were jumping up and firing their weapons and yelling about a flag.”

Williams took out seven Japanese pillboxes that day — an incredible feat.

He continued to fight during the five-week battle, even after suffering a shrapnel wound to his leg. When the war ended, he returned to the United States and stood stiffly at attention on the White House lawn as President Truman presented him the Medal of Honor.

Williams says he doesn’t remember the president’s speech that day but does remember what he said to each of the men honored. He said: “I would rather have this medal than be president.”

“President Truman was a World War I guy and knew what was required to receive the medal. It had a meaning to him that no president we’ve had since could understand.”

Today, Williams is the sole surviving Marine from World War II to wear the Medal of Honor.

After the war, Williams returned to West Virginia, settling in Ona. For 33 years, he worked in the Huntington office of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as a veterans service representative, a job that allowed him to serve veterans and their families.

He also served as Commandant of the West Virginia Veterans Nursing Home at Barboursville for nearly 10 years, helping veterans who were often in their last years of life.

Since World War I, mothers who have lost a son in military service have been known as Gold Star Mothers. But, remembering when he delivered those dreaded telegrams in the early days of World War II, it had always bothered Williams that there was no recognition for other family members — the fathers, grandparents, brothers and sisters.

Convinced that “consideration and recognition of the families of those lost in military service was very inadequate,” he resolved to change that. To do so, he and his grandsons created the Hershel Woody Williams Medal of Honor Foundation.

In 2013, Williams and his foundation erected the first Gold Star Families Memorial Monument at the Donel V. Kinnard Memorial State Veterans Cemetery in Dunbar, West Virginia.

Since then, 59 Gold Star Families Memorial Monuments have been planned or erected in 45 states, with 63 others on the drawing board.

“We have seven in West Virginia and are getting ready to put a big one on the grounds of the State Capitol in Charleston in April. My dream is to see one erected in Washington, D.C.”

His many speaking engagements and frequent memorial dedications keep Williams traveling much of the time. In 2018, he was among 15 Medal of Honor recipients honored during the on-field coin toss ceremony before Super Bowl LII between the Philadelphia Eagles and the New England Patriots. Williams was chosen to toss the coin.

Citing his remarkable bravery on Iwo Jima and his unceasing efforts on behalf of veterans and their families, many call Williams a hero.

It’s a title he insists he doesn’t deserve.

“I often think about Iwo Jima, and I think about those Marines who were killed in that battle and never got to come home,” he says. “To me they are the true heroes.”