The story of how our hometown university was named in honor of Chief Justice John Marshall

By Jerome Gilbert & Joni Albrecht

HQ 117 | SPRING 2022

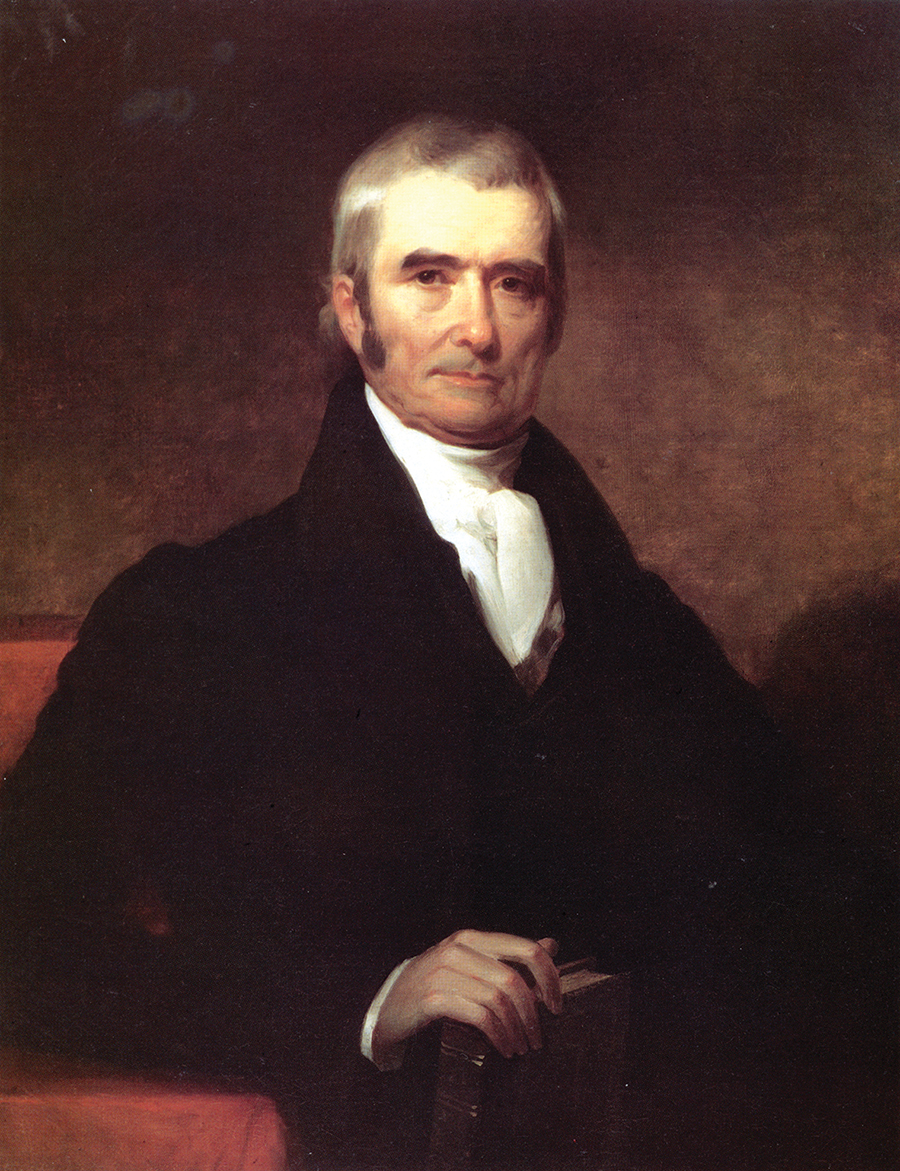

Residents of Huntington have likely visited the campus of Marshall University at some point in their lives. If you wander off Fifth Avenue and turn to approach historic Old Main on campus, you immediately are greeted by a larger-than-life statue of the great Chief Justice John Marshall. In mid-stride, outfitted in a judicial robe and holding a law book, the stunning statue makes a lasting impression on the physical connection between Marshall University and its namesake. But how did Marshall happen to be memorialized in Huntington? And what should we know today about this somewhat mysterious giant of American history?

Even though many in the field of law know about John Marshall, he is not emphasized today in the history books of schoolchildren or even college students to the level of Washington or Jefferson or the other Founding Fathers. Some may say Marshall is the least known Founding Father, while others may not give him the recognition of founder. However, Marshall’s story mirrors America’s own and is central to understanding not only the early republic but also how America operates today. A number of recent biographies have begun to tell a larger story of the life and career of John Marshall. Certainly, it would be a massive oversight not to mention the late Marshall University professor Jean Edward Smith who wrote a brilliant biography in 1996, John Marshall: Definer of the Nation. Smith’s book is filled with interesting facts about Marshall not found in the history books.

Many people know that John Marshall was the fourth and the longest-serving chief justice in the history of the Court, having served from 1801 until his death in 1835. What may be interesting to Huntingtonians is that Marshall was friends with John Laidley, a prominent Virginia lawyer and politician in Cabell County, Virginia (later Cabell County, West Virginia, changed during the Civil War). Laidley wanted to honor his friend Marshall and did so in 1837, two years after Marshall’s death, by naming a school in Cabell County after him: Marshall Academy. That Academy has persisted for 185 years and today is known as Marshall University. In fact, just north of John Marshall’s statue near Old Main was the very site where the log cabin was situated that was the original Marshall Academy.

Marshall University is not the only place in America where the great chief justice is memorialized. In Richmond, Virginia, where he lived the majority of his adult life, stands the John Marshall House, a Federal-style home Marshall built in 1790. Today it is owned and operated by Preservation Virginia (PV) as a museum. While in Richmond visitors can also travel to the Shockoe Hill Cemetery and find the inauspicious final resting place of John Marshall next to his beloved wife Polly. Beginning in May, visitors can view Marshall’s 1806 judicial robe, restored through efforts of PV, the John Marshall Center for Constitutional History & Civics and the Virginia Museum of History & Culture (VMHC). The robe will be on display at the VMHC for five years.

In Washington, D.C., an impressive bronze statue of a seated John Marshall presides over Pennsylvania Avenue in the John Marshall Memorial Park. And yet another Marshall bronze holds court inside the U.S. Supreme Court building. Visitors to D.C. may not have the John Marshall Memorial Park on their list of must-see spots, but for those associated with the Supreme Court or the law, John Marshall is well known and highly regarded.

In fact, in a 2016 interview, the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said that her dream dinner guest would be Chief Justice John Marshall. Surely part of her wish was based on John Marshall’s well-known flair for entertaining, often with large amounts of Madeira wine from the barrels in his basement, but perhaps the larger reason would be his brilliant legal mind with which he shaped the judicial branch of our government. If you visit the John Marshall House, you can see those same Madeira casks in the basement and the table setting in the dining room brought back from France after his investigation of what became known at the XYZ Affair.

Interesting facts about the great chief justice abound: He was largely self-educated, lied about his age so that he could enlist in a militia during the American Revolution, served with General George Washington at Valley Forge, was a cousin to Thomas Jefferson who was his political rival, studied one year under George Wythe at the College of William & Mary, turned down Washington a number of times for judicial and cabinet appointments, served under President John Adams as secretary of state before Adams appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1801, wrote the first biography of George Washington who was his hero, established the principal of judicial review in the Marbury v. Madison case, ruled in favor of Native Americans in Georgia to the chagrin of President Andrew Jackson and died in 1835 in Philadelphia after an operation to remove bladder stones. For years he was commemorated on February 4 — the date he took the oath of office as chief justice — with poems, parades and speeches delivered throughout the country in cities big and small, many just like Huntington.

Remembering and retelling this history and connecting it to today is the main job of the John Marshall Center for Constitutional History & Civics, whose mission is to educate and engage learners about Marshall’s lasting contributions and judicial legacy. Located in Richmond, Virginia, the Center delivers programs to schools throughout the country about America’s constitutional founding and civics and sponsors in-person and livestreamed programs for the general population. That can mean exploring when the courts have failed the American people in addition to when they have triumphed. That can also mean examining Marshall’s involvement in slavery.

Recent research produced documentation verifying that Marshall’s participation in the institution of slavery was more significant than had been previously known. Like George Washington, John Marshall was a slaveholder; and his personal benefit from the labors of enslaved men and women blatantly contradicted his view that it was an evil institution. In Determined: the 400-year Struggle for Black Equality (2), the John Marshall Center asks students to examine these conflicts and to consider a nation founded on principles of freedom but practicing bondage. They are asked to identify how the judiciary has helped Americans work together toward a more perfect union.

They learn that our government today operates with three co-equal branches and that, had it not been for John Marshall, it is possible that the executive and legislative branches would overshadow the judicial. We can thank John Marshall for the strong Court that ruled in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 to begin to right the wrongs of segregation which was the regrettable legacy of slavery.

The citizens of Huntington and those of Richmond and beyond would be well served to study Marshall’s place in the history of our country and government, as complicated and imperfect as it is. They will discover that Marshall’s judicial legacy lives today, consistently upholding the Court’s authority to interpret the Constitution and the importance of a strong federal government and independent judiciary to our nation’s health. Current justices — from Breyer to Barrett — often name drop Marshall; Marshall Court citations numbered more than 30 in last year’s term alone. Perhaps most importantly, they will find that in a country still wending its way to a more perfect union, Marshall’s Marbury reigns supreme as a defender of justice.

In Marshall University’s impressive bronze statue of the renowned chief justice, Huntington residents have a physical reminder of the promise of equal justice and an homage to one of America’s greatest legal scholars. They may want to venture beyond the statue and discover the whole history of the chief justice by going back to Richmond. The complete story of John Marshall is now being revealed there through the programming of the John Marshall Center and at Preservation Virginia’s John Marshall House.