Heralded as the greatest American writer since Ernest Hemingway, this is the long-overdue story of the Milton native’s brilliant and tragic life.

By Michael Friel

HQ 120 | WINTER 2023

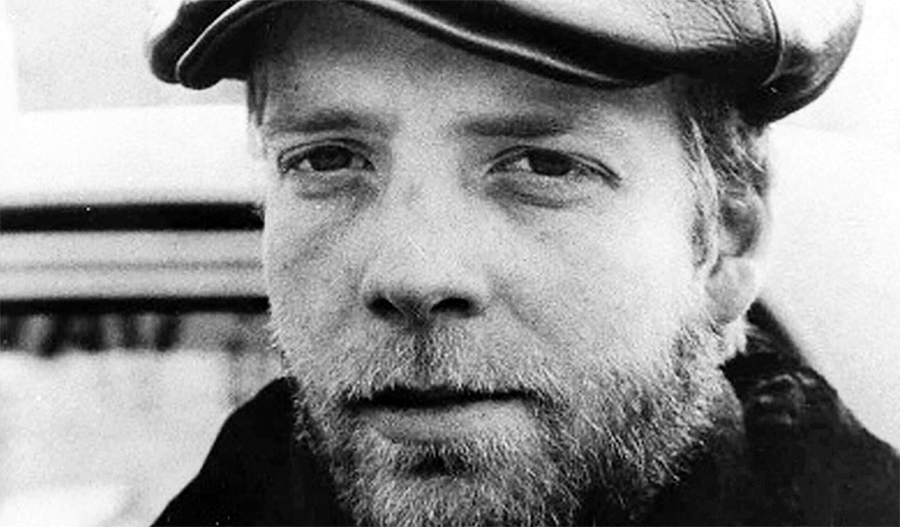

Breece Pancake burst onto the literary scene in 1977 — a brilliant, dazzling light out of nowhere. Author Mike Murphy said he “may have been the best American writer of his generation.” The venerable Kurt Vonnegut in a letter to author John Casey wrote, “I give you my word of honor that he is merely the best writer, the most sincere writer I’ve ever read.” Literary giant Joyce Carol Oates proclaimed Pancake to be “a young writer of such extraordinary gifts that one is tempted to compare his debut to Hemingway.” And English novelist and poet James Lasdun recently chose Pancake’s story Hollow as the best story of the 20th century.

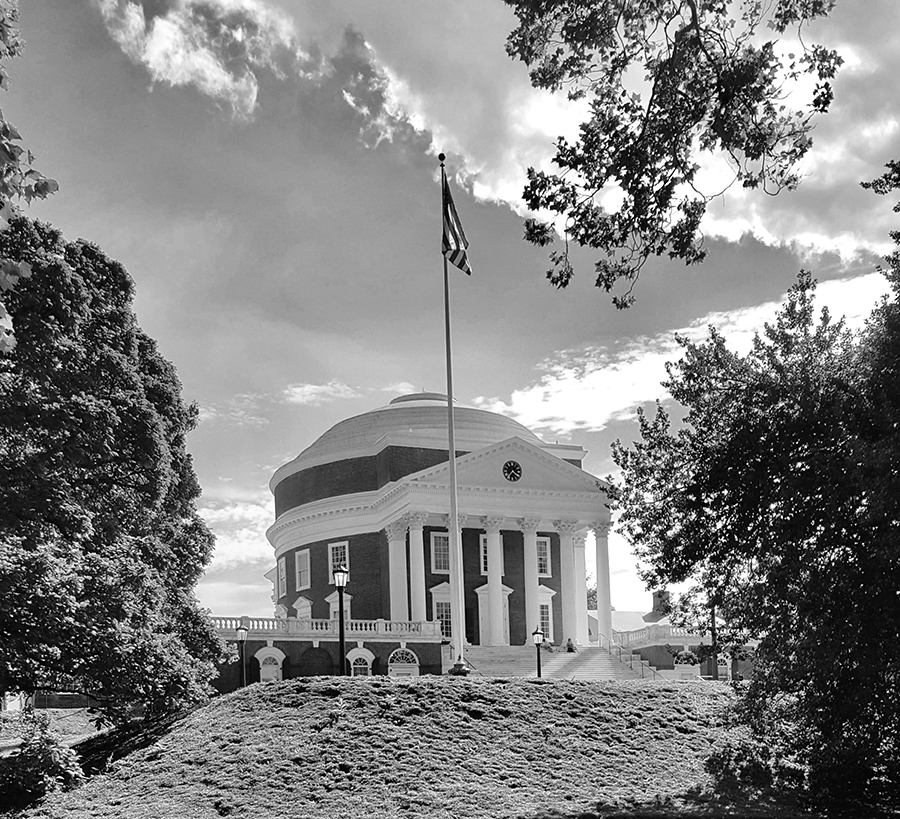

Pancake, a Milton native and son of Marshall University, had landed a prestigious writing fellowship at the University of Virginia in 1976. He soon realized every young writer’s dream: He sold a short story, Trilobites, to The Atlantic Monthly. Within a year, additional stories appeared in The Atlantic and other national publications. The New Yorker solicited his work. Publishing giant Doubleday asked for a novel.

Then, suddenly, just as Pancake teetered on the brink of bona fide fame, the 26-year-old writer, for reasons unclear, extinguished his life and literary career with a shotgun blast to the head on Palm Sunday 1979.

• • • • • •

A lot has changed in Milton since Breece grew up here. Where his childhood home once stood along U.S. Route 60, today a Wendy’s beckons the hungry. Closed is the old bank on Main Street where Breece used to sit on the steps swapping stories with old-timers. Even the steps are gone.

Still, 43 years later, fans of Pancake make the pilgrimage to Milton from far-flung places across the United States and abroad to glean more about the writer and his slice of Appalachia.

They stop at the library where his mother Helen once worked. They’re greeted just inside by a modest display case of Pancake memorabilia, including an amalgamation of newspaper clippings and photos: Breece with his father, C.R., during Christmas 1970; an uncharacteristically clean-shaven Breece from his teaching days; Breece clowning around with family; directions to his grave (written by his mother). Visitors frequently trek to his nearby resting place to reflect. They leave small stones and other tokens as a show of remembrance and admiration.

Lynn McGinnis, library manager, is available to retrieve a Milton High School yearbook and point out Pancake’s boyish senior photo. “That’s the Breece I remember.”

McGinnis knew Pancake pretty much his entire life. As children they attended the same Methodist church. They were classmates throughout school and graduated from Milton High in 1970 before studying together at Marshall.

“Nothing about Breece really stood out,” McGinnis explains. “He was just one of us.” It’s the little things she remembers. Breece and another boy pulling up her dress in first grade. Breece debating religion with her father. Breece and his buddies exploring the surrounding hills and woods, searching for artifacts. The old green Army jacket he wore around Marshall’s campus.

After earning a degree from Marshall, Pancake taught at two Virginia military academies, where he began to write in earnest. He would teach during the day then write until the wee hours. He would write and rewrite, sometimes 10 or more drafts.

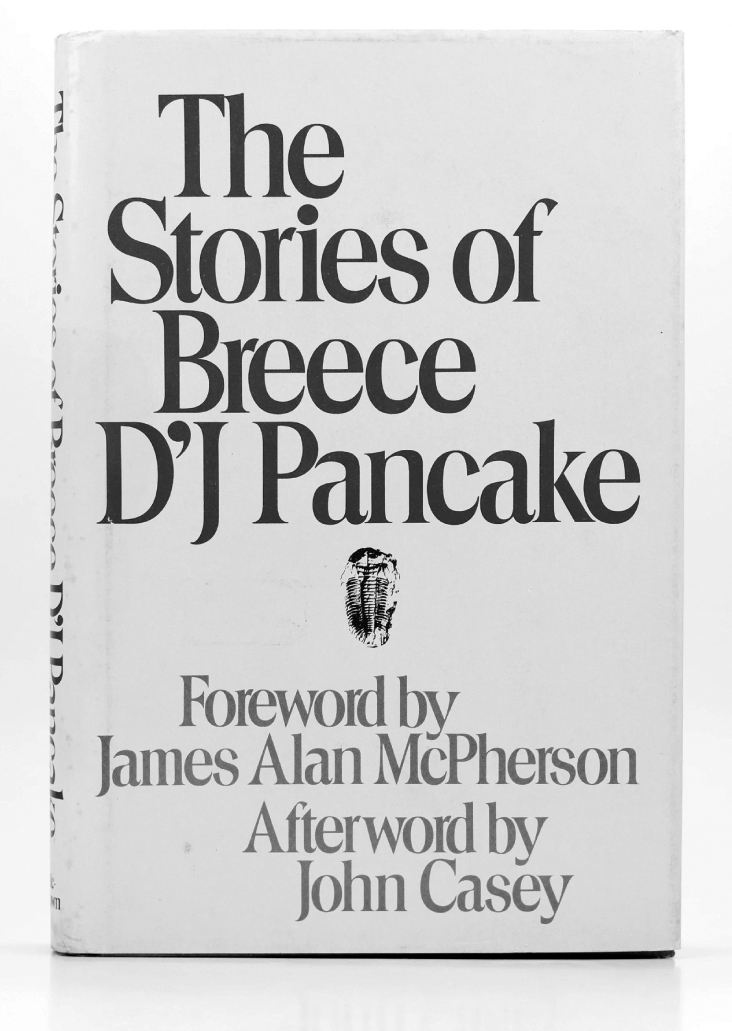

At the University of Virginia, Pancake felt like an outsider, a hillbilly among the Southern aristocracy. Sometimes he leaned into the stereotype. The Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist James Alan McPherson, who had just begun teaching there and eventually became a close friend, first met Pancake in 1976. In the foreword to The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake, McPherson said Pancake came lumbering down the hallowed halls of UVA wearing a flannel shirt, faded blue jeans and a big U.S. Army belt buckle, uttering in a distinctively Southern drawl, “I’m Jimmy Carter and I’m running for president.”

McPherson described Pancake as “wiry and tall, just a little over six feet, with very direct, deep-seeing brown eyes. His straw-blond hair lacked softness. In his face was that kind of half-smile/half-grimace. His favorite comment was ‘Bull shit!’ He wasted no words and rewrote ceaselessly for the precise effect he intended to convey.”

An article in The New Yorker explained that Pancake “never felt comfortable in the refined atmosphere of Charlottesville. In a letter home, he described how his landlady asked him to tend bar at a party she was throwing for the English department. ‘[She] said if I didn’t, she’d have to hire a colored, and they don’t mix a good drink. That tells me where I stand as a Hillbilly.’”

In his foreword McPherson wrote, “There was a mystery about Breece Pancake. He was a lonely and melancholy man. Yet there was also an antagonistic strain in him, a contempt for the conformity. And his position at the university … as a man from a small town in the hills of West Virginia … contributed some to the cynicism and bitterness that was already in him. He loved the outdoors and during those trips into the mountains he seemed to be at peace.”

Despite his personal struggles at UVA, he found professional success early on. While many young writers struggle in vain for years to get published, Pancake sold his first story to The Atlantic Monthly. His editor at the magazine said, “In 30-some years at The Atlantic,

I cannot recall a response to a new author like the response to this one. Letters drifted in for months, obviously from people who knew nothing about him, asking for more stories … or simply expressing admiration and gratitude. Whatever it is that truly commands reader attention, he had it.”

• • • • • •

“I open the truck’s door, step onto the brick side street. I look at Company Hill again, all sort of worn down and round. A long time ago it was real craggy and stood like an island in the Teays River. It took over a million years to make that smooth little hill, and I’ve looked all over it for trilobites. I think how it has always been there and always will be, at least for as long as it matters. The air is smoky with summertime. A bunch of starlings swim over me. I was

born in this country and I have never very much wanted to leave. I remember Pop’s dead eyes looking at me. They were real dry, and that took something out of me.” — Opening lines of Trilobites

Pancake’s stories are quintessential Appalachian. The narrative is shaped by history, folklore and geography. The landscape is harsh. His protagonists tend to be searchers, longing to escape a past they cannot quite let go. Pancake once wrote, “If only one thing is true to being a writer, it is to remain at once the most moral man and the most repentant sinner God could want.”

Pancake felt vindicated after being published. In a letter to his sister Donnetta, he wrote: “This has really set fire to Wilson Hall and the (cross yourself) English Department [at UVA]. Poor second-rate citizen Pancake who can’t speak the King’s English … who (God forbid) went to work when the money ran out — that turkey made it.”

The 12 completed stories Pancake left behind appear in the posthumous collection of his work, The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake, which has been reprinted multiple times since its 1983 debut. The Pulitzer Prize-nominated volume is studied in literature classes around the world. Pancake’s fans include not only Murphy, Vonnegut, Oates and Lasdun, but also such literary luminaries as the late Raymond Carver and Sam Shepard — to name a few.

Pancake was acutely aware of his status as a West Virginian. As McPherson noted he was “very self-conscious about the poverty of his state, and about its image in certain books. He told me he did not think much of Harry Caudill’s Night Comes to the Cumberlands. He thought it presented an inaccurate image of his native ground, and his ambition, as a writer, was to improve on it.”

• • • • • •

It’s hard to surmise why Pancake committed suicide. Like his father, he had a drinking problem that no doubt contributed to his melancholy. In fact, he had been drinking on that fateful day when, for reasons unknown, he wandered into his neighbor’s empty house and sat in the dark. When the family returned home, he fled back to his small house, took out a shotgun, placed it in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

In the years preceding his death, there were some clues that may have explained his state of mind. An article in The New Yorker noted that, “His father … died of complications resulting from multiple sclerosis in 1975. Three weeks later, his closest friend, Matthew Heard, was killed in an automobile accident. And, in 1977, his girlfriend, Emily Miller, bowed to pressure from her well-to-do family and rejected Pancake’s marriage proposal. ‘Her parents have decided I’m not good enough for her,’ he wrote to his mother after Emily spurned him.”

But perhaps these words by his mother shed the best light of all: “God called him home because he saw too much dishonesty and evil in this world and he couldn’t cope.”

• • • • • •

In a cemetery on a hill not far from downtown Milton, Pancake was laid to rest next to his father. His mother joined them upon her death in 2014. In the end, Breece got what he longed for: to return home.

In a September 1974 letter to his parents while teaching in Virginia, a homesick Pancake wrote: “I’m going to come back to West Virginia when this is over. There’s something ancient and deeply rooted in my soul. I like to think that I left my ghost up one of those hollows, and I’ll never be able to leave until I find it — and I don’t want to look for it because I might find it and have to leave.”