Under the leadership of Courtney Proctor Cross, the Huntington Cabell Wayne Animal Shelter has reduced its euthanasia rate from 50% to 3%. That equates to saving the lives of 1,400 dogs and cats each year.

By Katherine Pyles

HQ 125 | SPRING 2024

Sometimes, the question “If not me, then who?” has an answer. And in Huntington, that answer is often Courtney Proctor Cross.

There’s the Courtney who stopped the city from needlessly cutting down trees by chairing the Urban Forestry Advisory Committee to protect Huntington’s living landmarks. There’s the Courtney who taught hundreds of children at Cammack Middle and Cammack Elementary, then hundreds more at Southside Elementary when the schools were renovated and renamed — and the Courtney who, during those renovations, spearheaded the effort to save the original building’s façade. Amidst these pursuits and more, from serving at her church to caring for her family, she has always had a soft spot for animals. This is the Courtney you’ve probably seen in some strange places — coaxing dogs out of intersections, climbing trees to rescue cats, wading through Four Pole Creek with a puppy nestled in her arms — and whose most recent labor of love has been to virtually eliminate euthanasia at the Huntington Cabell Wayne Animal Shelter.

There’s only one Courtney Proctor Cross. But for the causes closest to her heart, Cross does the work of many.

“Every community deserves at least one Courtney Proctor Cross,” said Huntington Mayor Steve Williams. “The thing is, Huntington has several incarnations of her.”

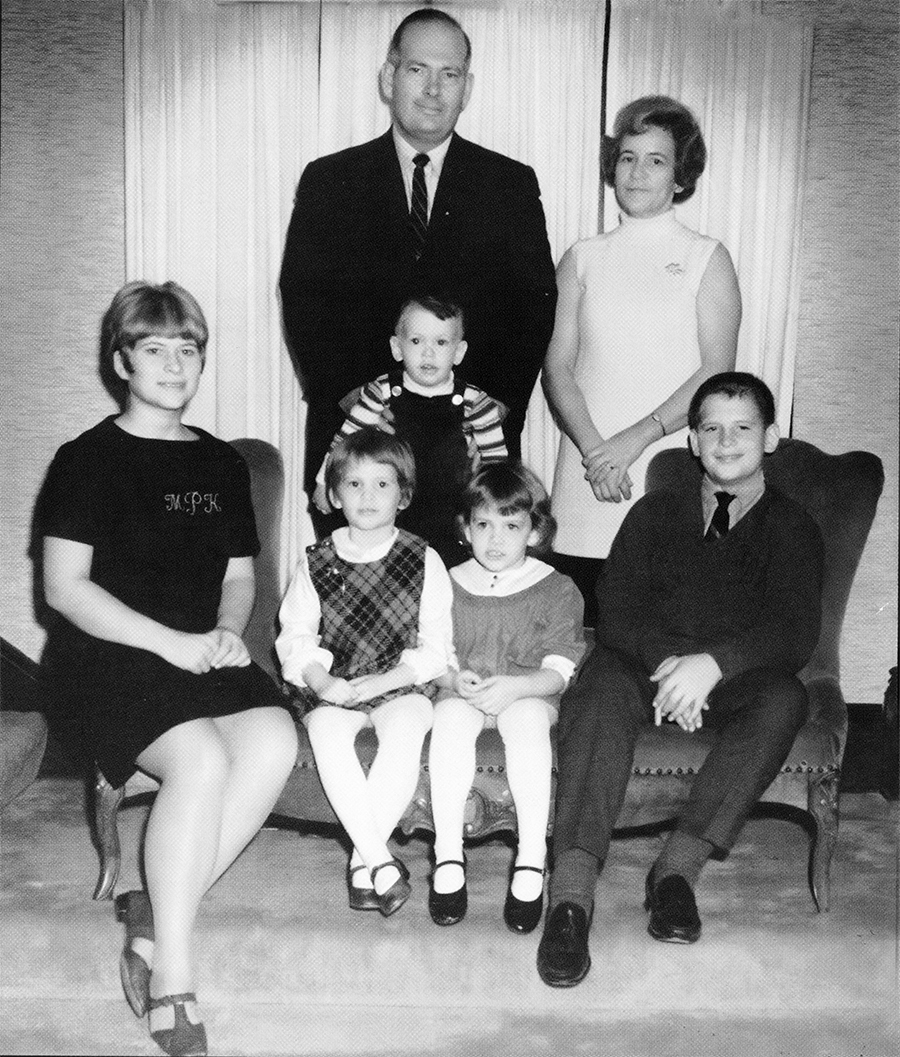

Cross’s own story is intertwined with Huntington’s in ways most can only fathom. The daughter of Courtney and Herbert “Pete” Proctor, Cross was only 6 years old when she lost both of her parents in the Nov. 14, 1970, Marshall plane crash. When she and her four siblings were split up among extended family, Cross, along with her sister Patricia, moved to Fayetteville to live with her aunt and uncle.

Growing up, Fayetteville felt like home, Cross said. But somehow, so did Huntington.

“My older siblings were here, and my brother John who is younger than me was living in Huntington with my sister Kim,” Cross explained. “I’d come to visit in the summer and reconnect with family and friends — our old neighbors, kids I used to play with, friends of my mom and dad. I’ll always love Fayetteville, but when I came back here it just felt like home.”

Cross, whose grandmother earned her teaching degree from Marshall in the early 1900s, knew from an early age that she wanted to be a teacher. She spent countless hours playing school with her dolls, holding class on the wraparound porch of her aunt and uncle’s Queen Anne-style home. When she wasn’t make-believe teaching, she was running a very real animal rescue operation, riding her bicycle around Fayetteville with a menagerie of lost and stray pets tucked in the basket.

“I was never allowed to keep the animals I found,” she said. “But there was this sweet lady — and looking back, she was probably a cat hoarder or something — who would always take in the kittens I found.”

Always having a sense she’d return to Marshall and Huntington, both to honor her parents’ memory and to heal her own grief, Cross enrolled at Marshall in 1982. She earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education and in 1989 began her teaching career at Cammack. Cross married and had a son, Fisher, who would go on to work for Marshall in the athletics department before entering medical-surgical sales. Fisher was the keynote speaker for the 2017 Memorial Fountain Ceremony, the first time someone born after the plane crash was asked to speak.

Beloved by her students, Cross quickly made a name for herself outside the classroom as well. She was a familiar face at Huntington City Council meetings, where she’d show up to protest the unnecessary removal of trees around the city.

“I’d get so upset when people would cut down trees that were beautiful and healthy — and why? Just because someone doesn’t want to rake leaves?” she said. “At one point I was referred to as a ‘tree-hugging wingnut,’ and I said, ‘I’ll take that as a compliment, thank you very much.’ I love trees; they make a tremendous difference in so many ways. I can’t imagine living somewhere where there were no trees.”

Cross’s persistence soon led to a lunch meeting with new councilmember Steve Williams, who was just beginning his career in public service.

“I can’t remember a time in my adult life when I didn’t know of Courtney Proctor Cross; she is legendary among those who are civic minded,” Williams said. “When we met, it was as if two kindred spirits had just joined.”

Cross was named Citizen of the Year in 2014 by The Herald-Dispatch, which came as no surprise to Williams. When asked to weigh in on the “tree-hugging wingnut” nickname, Williams laughed, insisting that Cross’s passion is infectious, not irritating.

“No, no, she just suckers you in on all this,” he said, recalling a time he opened his car door for a stray terrier mix and phoned Cross — and the next thing he knew, he was helping arrange a rescue transport to Pennsylvania. “And somehow, you’re happy doing it.”

Proving herself a reliable expert on whether a tree needed to be cut down or simply pruned, Cross was invited to head up the city’s Urban Forestry Advisory Committee, which consults with the Public Works Department on tree-related issues and coordinates tree-planting projects. Williams noted it’s largely thanks to Cross that Huntington is named a Tree City USA community by the Arbor Day Foundation year after year.

“It helps in our public positions to have people you can just trust,” he said. “Not trust and verify. Just trust.”

In 2018, Cross approached Williams with an idea. She told him she’d like to serve as the executive director of the Huntington Cabell Wayne Animal Shelter, where a lack of coordination between the shelter and animal welfare groups had contributed to an alarmingly high euthanasia rate. With more than a decade of involvement in local animal rescue efforts, Cross knew what she was up against — but the thought of putting an end to the shelter’s needless killings wouldn’t leave her.

“Anywhere from 50-75% of the animals that entered the shelter were being euthanized,” Cross said. “I wasn’t ready to quit teaching — but when the opportunity presented itself, I felt like I needed to see what I could do.”

What she could do turned out to be a lot. Prior to Cross’s hiring, the animal shelter took in 3,000 dogs and cats a year. Of those, 1,500 or more were euthanized. Today, under Cross’s leadership, the animal shelter still takes in 3,000 dogs and cats a year, but the number euthanized is down to just 100, mostly due to severe medical issues or to prevent suffering. In essence, Cross and her network of volunteers are saving the lives of some 1,400 dogs and cats each year.

“It would have been impossible to turn things around without the help of the community, the rescue groups, the fosters, the transporters and everyone else in this whole big life-saving network that we have,” Cross said.

She said she’s especially thankful for organizations like One By One Animal Advocates and ASAP (Advocates Saving Adoptable Pets), which regularly provide medical care for sick and injured animals and pull animals from the shelter to send to their rescue partners around the country. Cross noted that the shelter’s animal control board has also been supportive, as have local veterinarians who regularly treat shelter animals. And the shelter staff takes great care of the animals, she added.

“There could have been so many roadblocks,” she said. “It could’ve been a nightmare. But it hasn’t been. We could never have achieved the myriad changes that have happened over the past six years if we had not worked together for the good of the animals — and I am grateful to my community, my family and my rescue friends for making all of this possible.”

Still, the shelter is always full, and the calls never stop coming in. With a nationwide downward trend in shelter adoptions and grant funding stretched thin, Cross and her network of supporters work tirelessly to keep the shelter afloat and euthanasia at bay. The work is life-consuming, she said, but what keeps her going is a single, sobering truth: “The thought of how many animals would not make it.”

“I’m not saying I’m not replaceable — but I’ve committed myself to this, and I’m going to see it through,” she said, when asked how long she’ll continue in the role. “There are a lot of people who have worked for a long time to bring about significant changes at the shelter, and, collectively, we’ve done that. I’m not just going to walk away from that.”

Some of the other changes Cross has implemented include opening the shelter to volunteers, who come in to walk dogs not only on the shelter property but also at local parks and around town. The shelter has added a roof, lights and fans to its outside kennels; built six storage buildings; installed security cameras; created playgroups for dogs; and constructed both a free-roaming cat room and indoor-outdoor runs for the dogs housed in the barn. New outdoor kennels are under construction to give dogs the freedom to spend their days outside.

Cross’s latest endeavor is her biggest yet: transforming the former Cook School across the road from the shelter into a multipurpose facility that will house a surgical unit (thanks to “an incredibly generous gift from a foundation,” she noted); medical intake; specially designed spaces for cats, puppies and small dogs; and a meeting room. A true community effort, fundraising for the project is ongoing and should allow the facility to open this summer. Cross’s husband, Patrick Hooten, has overseen the renovations and has done some of the physical labor himself to ensure every dollar is used judiciously.

“He cringes when I say, ‘I have an idea,’” Cross laughed. “He’ll say, ‘No, no, I don’t want to know what it is. Your ideas scare me.’ He has been a trouper. I couldn’t have done this — any of it — without his support.”

In addition to donating toward the Cook School project and other shelter improvements, Cross said people willing to foster dogs or cats are a huge help — even if only for a week or two to allow space at the shelter to open up or to give some of the more sensitive animals a break from the shelter environment. Additionally, she noted, the shelter’s finances are “always stretched thin,” but a new campaign seeks to change that.

“To give the shelter significantly more financial stability, we are currently focusing on a campaign to recruit 200 recurring donors at $25 a month, or less than a dollar a day,” she said.

Donations can be made and items from the shelter’s wish list can be purchased on the shelter’s website, www.hcwanimalshelter.com. The shelter is supported by the Western West Virginia Animal Rescue Alliance, a 501(c)(3) charitable organization. Cross said all donations are greatly appreciated.

“We have people who step up and do so many things for us,” she said. “We just need more of them.”

Or, some might say, we just need more Courtneys. If you ask Williams, they’re out there.

“I’m coming up on my 12th year as mayor,” he said, tears welling in his eyes, “and I’ve come to understand what a wonderful heart this city has. And if we were to put up a poster child for the heart and soul of Huntington, it would be Courtney.”

As for Cross, the work may be hard, but the choice to do it comes easy.

“Usually I just see something that I think is wrong, that makes me crazy or makes me sad,” she said. “And I’m just like, ‘I’ve got to speak up. I’ve got to try to do something about this.’”

If you would like to volunteer, donate gifts or become a recurring donor to the animal shelter, please visit www.hcwanimalshelter.com.