One of Marshall University’s most beloved professors is remembered.

By Bill Belanger

HQ 28 | SPRING/SUMMER 1997

Heads up everybody!” The words came in a low roar.

“March is not the only thing that comes in like a lion,” I muttered to the student next to me. Professor W. Page Pitt, head of Marshall College’s Journalism Department, strode to the big copy desk in the center of the classroom. The man had what we called in those days “a commanding presence.” Actually, we were in awe of him.

This was 1931, far from today’s world, where extremes in personality are so much the norm it is difficult to be distinctive. It did not bother Mr. Pitt that Marshall’s journalism department, not yet five years old, was not housed in a red brick building that was in architectural harmony with other campus buildings. The department that he founded spent its early years in a small green and white frame house facing Fifth Avenue near 17th Street.

The crowded little front room, serving as Pitt’s office, had two desks, one telephone and an ancient oak mantel, with a mirror. A guest chair of dubious vintage completed the decor. His secretary, Virginia Lee, needed no intercom. She and her boss shared the phone with a long cord when the department was organized in 1927.

The other room, a classroom, unconventional by any standards, accommodated a big semi-circular table with a cutaway known to newspapermen as the slot. Some students took their places around it to get closer to the enigmatic teacher. Others sat beyond hoping to escape his notice. A few of the desks held ancient (even in that time) Underwood typewriters.

A newspaper rack leaned limply against the wall. Theoretically it was for metropolitan newspapers, but it usually held a two-week old Wayne County News and the Hinton Daily News with a dateline from the previous semester. And yesterday’s Herald-Dispatch was always there.

It was the best semblance of a newsroom atmosphere Pitt could manage with minimum state funds during the Depression.

Although he was legally blind, rarely could students get by with absence or tardiness in class.

He was a complex character. Even his blindness was an enigma — a story oft-told is that friends would brush past him unrecognized, yet he was known to hail a student across the street and comment on the color of a necktie or a new hairdo. His own neckties were of conservative colors, chosen for him by his wife.

The blindness was the result of surgery for mastoiditis when he was somewhere between three and five years old. Many dates about Pitt’s life are subject to change, possibly depending on which news clipping you’ve read. Facts that were established include his birth in New York City in 1900. His father moved to West Virginia and owned part of a coal mine, where the younger Pitt worked summers.

After teaching high school English in the West Virginia school system, Pitt was summoned to Marshall in 1926 to teach journalism and serve as adviser for The Parthenon, the student newspaper, he did that and more beginning with only one course in feature writing. The following year he organized the journalism department with a focus on newspaper work.

Courses in radio technique were not yet taught because it was not part of Pitt’s experience. The late H.R. Pinckard, and James Clendennin, local newspaper editors, taught history of the press, editorial writing and copy editing.

As the world of mass communication expanded, the professor added courses in advertising, broadcast journalism (covering television as well as radio) and corporate relations. As the need for more courses became evident he added faculty who were specialists in various fields. A degree in advertising was first offered in 1970. Meanwhile physical changes were being made. The Parthenon moved from the old Chapman Printing Co. on Seventh Avenue and 10th Street to the campus journalism quarters.

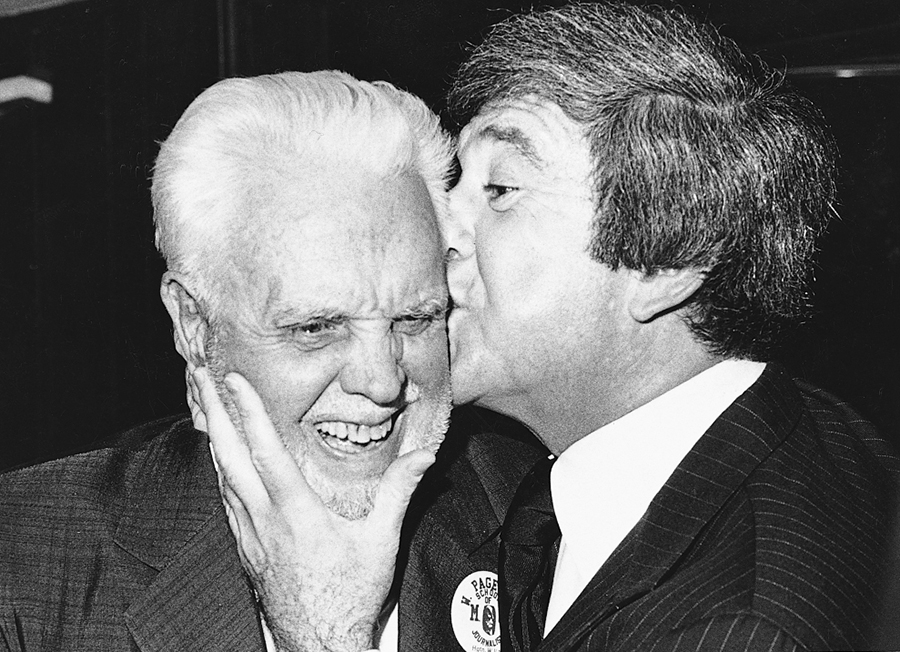

The department itself had long since moved out of the little green and white house to the basement of the expanding Morrow Library and a few years later to Smith Hall, where it is now located. A computer system was installed and in 1979 the department was upgraded to the status of an official journalism school. The following year, Pitt, who had retired in 1971, said when it was dedicated as the W. Page Pitt School of Journalism that having the school named for him was the happiest day of his life. Later the name was expanded to include other courses and today is known as the W. Page Pitt School of Journalism and Mass Communications.

He enjoyed “shocking” people. While many gave raving compliments to the colonial style Student Union (predecessor to the current Student Center) Pitt remarked in class that it “looks like Washington’s outhouse.” That was daring humor then, particularly before students. But it was characteristic of “The Grand Old Man of Journalism” who “liked to keep ‘em awake. ”

“The word ‘legend’ is one that’s often overused,” says James E. Casto, associate editor of The Herald-Dispatch, “but it’s the one that comes quickly to mind when the conversation turns to Page Pitt.”

Casto, who studied under Pitt in the early 1960s, has three published books and (like Pitt) dozens of freelance magazine articles under his by-line. And he’s quick to credit Pitt for helping get his journalistic career off to the right start.

“I took Pitt’s class in feature writing,” says Casto, “although there were lots of days when we talked about most everything but feature writing. One of the things that made Pitt such a remarkable teacher was his wonderfully unpredictable nature. Most of the time our textbook was that morning’s newspaper and the subject of discussion was that day’s big story — or then again, maybe something Pitt had been arguing about with the other fellows down at the Elks Club.

“I suspect I learned more about the actual mechanics of writing from others, first at Marshall and later at The Herald-Dispatch. But from Page Pitt I learned that good stories are where you find them and the world is full of them if you know how to smell them out. Pitt may have been blind but he could smell a story for miles. I consider myself privileged to have studied under him.”

What about the man as a person? Depends on whom you ask. Strong willed, unyielding on any point of controversy is the most frequent reaction. During the 1930s, The Parthenon staff went on strike because Pitt demanded the right to censor the student newspaper. Although he lost the decision to a compromise, he never admitted it. But at another time, when a faculty member dared to differ on a question of professional ethics, Pitt admitted freely, “I was wrong.”

Who could be neutral or impartial about Pitt? Whenever he heard (and he heard it often) that people either loved him or hated him, his reaction was the same: “I don’t care what they say, just as long as they say ‘Pitt.’”

At times flamboyant in his lifestyle, he was quick to anger, slow to forget and could always show warmth.

When friends called him a politician they may have been kidding. But the feisty journalism teacher held strong friendships with Republicans in power while admitting they did not always agree. His political acumen benefited his school. And at least once it benefited him.

During the mid-1930s the local newspapers reported he would be replaced on the faculty. But a few days later a story indicated the state board had made other arrangements and Pitt would resume teaching.

Above all else, Pitt was diverse excelling at chess, bridge, bowling and fishing. And remember, this man was blind. But for all his independence, one of his greatest interests required help — reading. Many a Saturday morning I (and other students) would read to him for a few hours from books or magazines of his choice. The reward was a luncheon that could not be found elsewhere. He was a gourmet cook.

When I was a sophomore his specialty was omelets — delicious but never tasting of eggs, which I detest. His strong point was the one-dish meal, which one could only guess the contents although the taste was never in question.

Diversity also applied to the jobs for which his students qualified even when courses were limited to a few subjects. Many, of course, went on to newspapers after graduation. Others found careers in advertising, public relations, publishing and magazine writing.

For Pitt, the more things changed the more they stayed the same. In earlier years he seemed to have little respect for the textbook, though he occasionally referred to it, whether to keep students prepared or uncertain no one knew. For most classes he thought it more relevant that students subscribe to a newspaper than to buy a book that, like computers of today, could become obsolete all too soon.

Subscriptions were sent to the Journalism Department so students could compare how different papers handled the same story. During the Lindbergh Kidnap story and the trial that followed, we learned more about the volatility of news than any textbook could detail.

When he taught a class in magazine writing, he demonstrated that if one has writing talent and an interest in various subjects, he or she can freelance. He was a frequent contributor to magazines — detective, western, adventure fiction (to the pulps.) His pen-name was Roy Page. With the “slicks” he was better paid but not as often, writing articles based on his own hobbies. In August 1967, Reader’s Digest published an article titled “My Most Unforgettable Character.” Its author? Virginia Daniel Pitt, his wife.

When the department he created expanded its subjects, the modern students of computer assisted reporting, layout, graphic design and photography went into careers without limits.

The United High School Media probably tells more about his vision than any of his projects. Originally called the United High School Press, it is a convention that draws high school journalism students interested in media careers to Huntington for workshops, awards and contacts. Originally the focus was on newspapers but as television, radio and general communication expanded, so did the convention.

A list of distinguished careers that resulted from Pitt’s labors would be too long but a few worth noting include Jack Maurice, Pulitzer prize winner and retired newspaper editor in Charleston; Soupy Sales, nationally known entertainer and stage/TV personality; Burl Osborne, president of the publishing division of the A.H. Bolo Corporation and CEO of the Dallas Morning News; Marvin Stone, former editor of U.S. News & World Report; Jim Comstock, founder of famed West Virginia Hillbilly; Gordon Kinney, senior vice president of The Ad Council; Gay Pauley Sehan, senior editor at UPI.

The student who turned to me and whispered, “Bet he doesn’t go out like a lamb” was right. (The student was Pulitzer prize winner, Jack Maurice.)

Old and ailing, Pitt died in a hospital in Florida in 1980.

Ask anyone who knew him, and they would attest that his fiery spirit and refusal to let a handicap limit his life lives on.

His former student and colleague, Dr. Ralph Turner, expressed it best, gesturing toward a classroom. “He is still here, still with us, not only in this school but wherever. The legend still inspires us all.”