By James E. Casto

HQ 58 | SUMMER 2006

In the Great Depression, hundreds of banks failed and thousands of Americans saw their life savings vanish. Determined that the nation never again would witness such a sad situation, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Congress in 1933 created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., which insures the deposits in member banks.

But in the era before insured deposits, it wasn’t just financial panics that endangered customers’ cash. When bandits held up a bank, it was the bank’s depositors who bore the loss. So, banks of that bygone day relied on huge iron vaults and armed guards to not only protect the bank’s deposits but also assure customers that their money was safe.

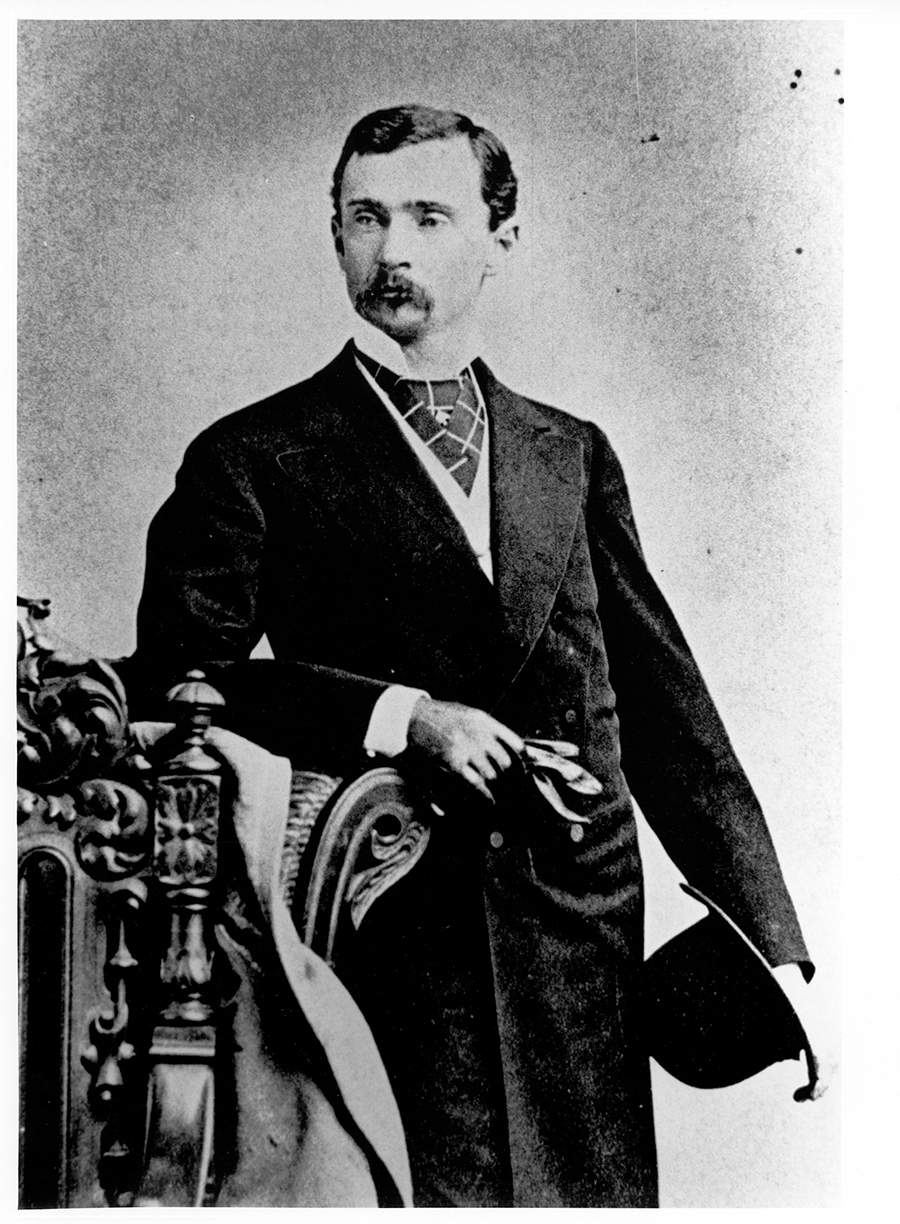

Thus it was that John Hooe Russel (1842-1903), president of the old Bank of Huntington, kept a pair of ivory-handled Colt revolvers on his desk, in easy reach if needed. As fate would have it, Russel was at lunch on Sept. 7, 1875, when four armed men robbed the bank and made their successful getaway.

Newspaper accounts of the holdup told of how two men, revolvers drawn, entered the bank, while two others watched outside. Cashier Robert T. Oney was alone in the bank. He lunged for one of the pistols on Russel’s desk but wasn’t fast enough. The two bandits jumped over the counter and picked up the two guns.

Forced at gunpoint, Oney opened the safe and the robbers grabbed the cash, said to be about $10,000. While the robbery was in progress, a messenger known only as “Jim” had entered the bank, and the two robbers marched Oney and the messenger out the door and across the street to where the other two bandits were waiting with the four’s horses.

At this point, Russel, returning from lunch, saw what was happening and ran into the bank for his pistols but found them gone.

A chase ensured as the bandits galloped out McCoy Road (past where the Huntington Museum of Art now stands), with Russel, Cabell County Sheriff D.I. Smith and 20 or so armed citizens in pursuit. The posse trailed the bandits into Kentucky before being forced to abandon the hunt and turn their worn-out horses back home.

But when one of the bandits was captured some weeks later in Tennessee, he was found to have not only several thousand dollars in cash but also one of Russel’s Colt pistols. He was returned to Huntington, tried, found guilty and sentenced to 14 years in the West Virginia Penitentiary at Moundsville, where he died without ever admitting his guilt or identifying any of the other armed robbers with him that day.

Local legend has it that it was famed outlaw Jesse James or maybe his brother Frank who led the gang that robbed the Bank of Huntington, although most experts on Western history are skeptical of that claim.

Whatever the identities of the bandits, the robbery provided a colorful chapter in the early history of Huntington. And, fittingly enough, in Russel it featured one of the young city’s most prominent citizens.

Born in Huntsville, Alabama, on June 15, 1842, Russel was one of the first businessmen to recognize the promising opportunities available in the new city of Huntington, founded by rail tycoon Collis P. Huntington as the western terminus of his Chesapeake and Ohio Railway.

Arriving in the new town in 1872, Russel initially entered the grocery business but when the Bank of Huntington, the city’s first, was organized, he became its cashier. He was named its president following the death of the bank’s first president, Mayor Peter Cline Buffington. (Over time, the Bank of Huntington evolved into the First Huntington National Bank, one of West Virginia’s leading banks and a direct antecedent of today’s Chase Bank.)

When he took over at the Bank of Huntington, Russel was said to be the youngest bank president in the United States.

Russel was active not only in the new town’s business affairs but its social circles as well. A son of the aristocratic Old South in every sense of the word, he was the chief organizer and long-time president of the Gypsy Club, known for its exclusive membership list and its elegant dances. He was one of the founders of the Trinity Episcopal Church and was a vestryman there for nearly 30 years.

His first wife was Nettie M. Phelps, of Richmond, Kentucky. She died soon after the birth of John Hooe Russel Jr., who lived only a bit more than a year. His second wife, Minerva Parke Phelps, was a cousin of his first wife. They had a son, Albert Lacy Russel, who was born in 1902 and grew up to be a prominent Cincinnati lawyer.

Local historian George S. Wallace, writing in his Cabell County Annals and Families, published in 1935, was high in his praise of Russel: “It was undoubtedly the presence of such men as he that was responsible, in a large degree, for the city’s phenomenal growth. He had a high degree of civic pride, a keen business judgment, and through his social graces contributed much to the morale of the growing community.”