Huntington’s heaviest hitters on the crab theory and the future

By Jack Houvouras

HQ 17 | SPRING 1994

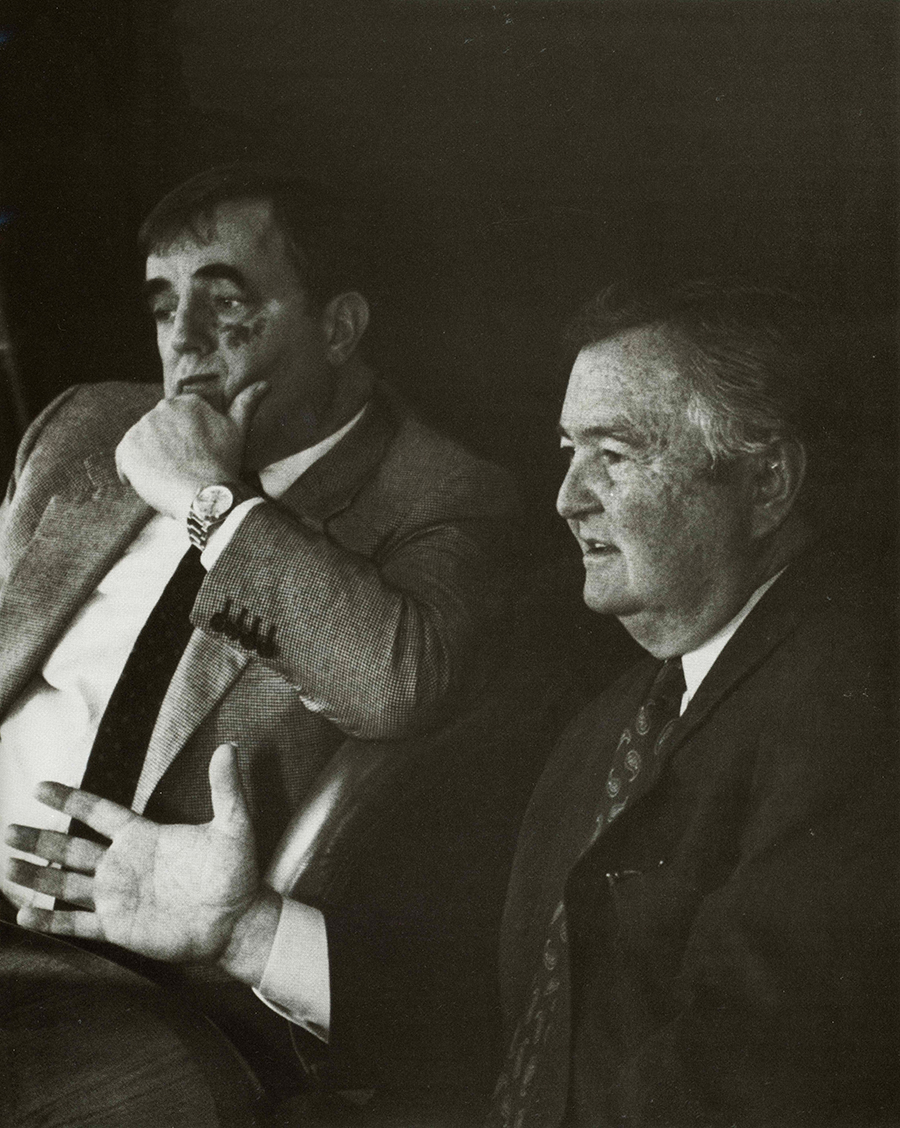

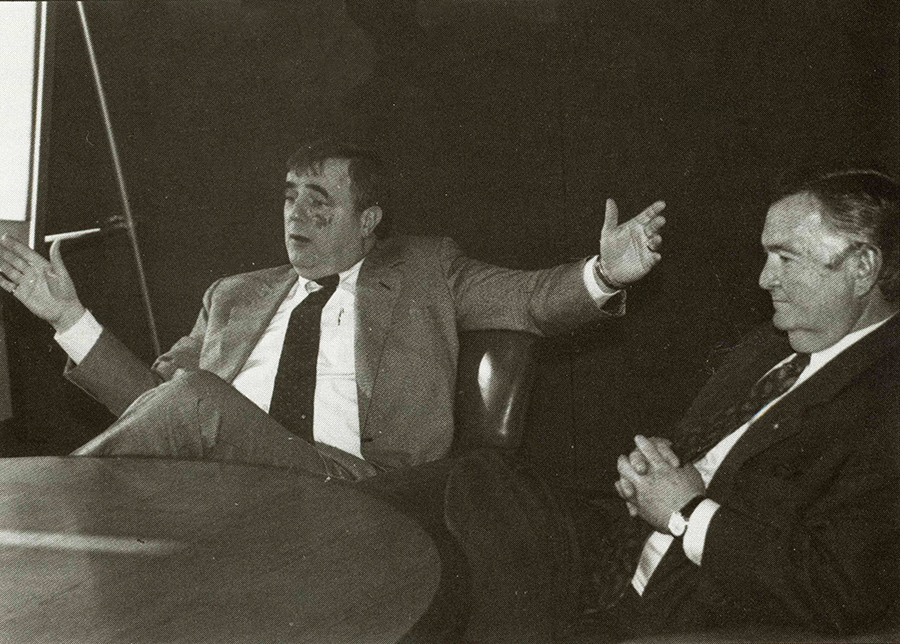

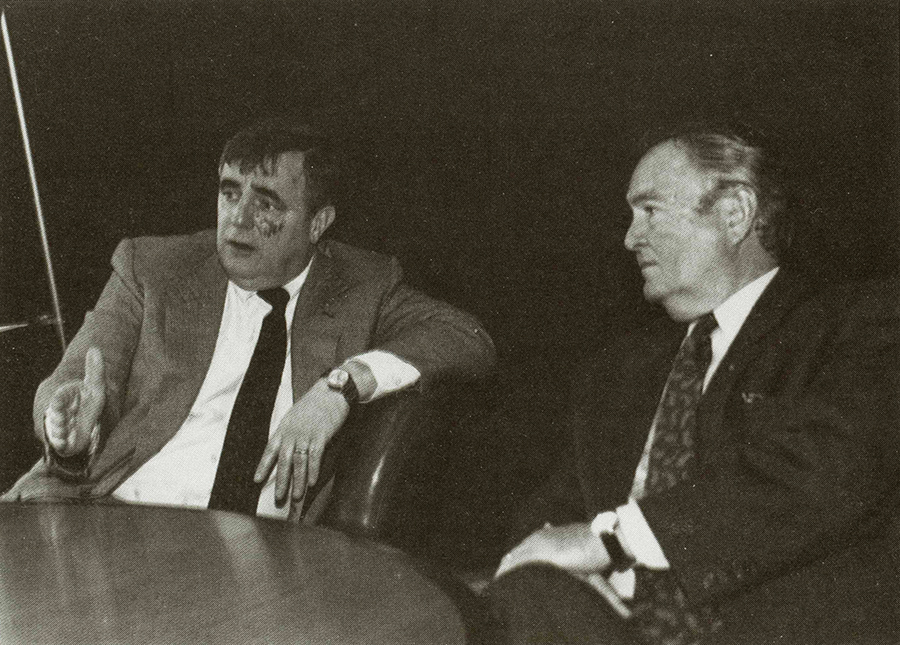

Looking back at the history of Huntington, it would be difficult to find two individuals who have done more for the city than Marshall T. Reynolds and A. Michael Perry. Their story dates back to 1964 when Reynolds, an upstart entrepreneur who had just bought the Chapman Printing Co. from his former boss, went looking/or a loan. While scouring the area for some money to get started, he was turned down by virtually every bank in the city, the most noteworthy of which was the First Huntington National Bank. “I’ll own this damn bank one day, ” Reynolds vowed as he left the building.

Reynolds and the bank crossed paths again years later when he offered to buy some of their used equipment. First Huntington then brought in A. Michael Perry, one of Huntington’s top attorneys, to represent them in the matter. Reynolds was so impressed with Perry during the negotiations that he asked him to represent his company in future dealings. Meanwhile, Reynolds began accumulating large blocks of stock in First Huntington and by 1980, gained controlling interest. His vow to own the bank one day was now a reality. He then convinced Perry to take over as the bank’s president. With the two men at the helm, the bank grew to become the largest financial holding company [Key Centurion] in West Virginia. Over the years, the two used the bank as a power base to effectuate dramatic change within the state, creating countless hundreds of jobs. In 1993, Key Centurion was sold to Bank One, one of the ten largest bank holding companies in the nation. The stock soared in a move that experts described as beneficial for everyone involved.

Since that time, Perry has been appointed as Banc One’s chairman and C.E. 0. for West Virginia. He is involved in an array of activities including chairman of the Huntington Regional

Chamber of Commerce, member of the West Virginia Round Table and member of the Huntington Area Development Council.

Reynolds, on the other hand, has taken his printing company public. Champion Industries, Inc. premiered on the NASDAQ on Jan. 28, 1993 for $10 a share. The company, which already owned printing plants in Huntington, Charleston, Parkersburg and Lexington, Ky., quickly expanded acquiring several companies throughout the Southeast. By Jan. 20, 1994, the stock had split 5 for 4 and in March was trading for nearly $25 a share.

I sat down with Reynolds and Perry on a cold, wintery February morning for the premiere of the HQ Interview. Their chemistry was still intense as the tape recorder began rolling …

HQ: We are meeting today in the executive offices of a bank holding company [formerly Key Centurion Bancshares, now owned by Bank One] that you built together from the ground up. What has made your professional relationship so strong?

PERRY: The uniqueness of the relationship started many years ago while I was practicing law. Marshall is the greatest offensive player I have ever seen from a standpoint of seeing potential. I guess my forte was seeing what could go wrong. I would express my concerns and Marshall would make a decision. It was clear from the start of our lawyer/client relationship that neither of us would ever look back and say, “I was right and you were wrong.” Very early on he said to me, “Don’t write me a memo. If our relationship can’t be supported by a handshake, then we shouldn’t be working together.” It has been the most unique relationship I have ever had.

REYNOLDS: Mike was one of the few legal people that I had dealt with who seemed to understand the big picture -maybe argued with it but nevertheless understood it. Obviously anytime you are in a relationship you’re exposed to betrayal. But, you really have to expose yourself to that to win. Fortunately for me, Mike Perry was, and still is, a guy of impeccable character.

HQ: Although you both share many ideas, you are also very different. In fact, while Mr. Reynolds is a Republican, Mr. Perry is a Democrat. Does it ever get in the way?

REYNOLDS: No it doesn’t get in the way. Everyone should have their own identity. I became a Republican when I saw all the problems going on up at the statehouse with Governor Baron and that crowd. I honestly thought that the only guy who had a chance of saving the state was Arch Moore. And as we look around Huntington, whether it’s the football stadium or the twin towers or the east Huntington bridge, or anything else where government has been supportive of us, it was during Gov. Moore’s first two terms. That’s when Huntington really turned the corner and began to improve. Obviously I think he really fouled up his last time out. It’s funny that while I am a registered Republican and Mike is a registered Democrat, I’m probably the liberal one.

PERRY: I can’t think of any instances where it has ever been a problem, and we’ve really had separate spheres. Marshall has worked primarily on a local level while I have worked predominantly on a statewide level.

HQ: What are some of your fondest memories of growing up in Huntington?

PERRY: My fondest memories are of my family, my church and always being surrounded with love. I was fortunate to have Sunday school teachers like George Brownfield, school teachers like Maxine Sullivan and coaches like Doug Greenlee who were concerned about you as a human being. I was fortunate to be raised in the west end where all your neighbors felt a responsibility to look after the children and discipline them if necessary. And I was fortunate to have to work -to learn the value of hard work and sacrifice.

REYNOLDS: Certainly some of my fondest memories would be during the Christmas season when my oldest sister and I would come to town to buy presents for our little brother and mother and father. At that time, downtown Huntington was an exciting place to be with the crowds and the snow. I remember pooling my money together with my sister so we could get some decent presents. But just the memories of the city, all the people, the excitement of Christmas and the· love I had for my father and my little brother Doug … those have to be some of my fondest memories.

HQ: Each of you have been extremely successful in your respective fields. At one point in his career, Mr. Reynolds had the opportunity to retire early and move his family to Hawaii. And Mr. Perry, who graduated at the top of his class in law school, could have worked anywhere in the country? What made you decide to stay in Huntington?

PERRY: I had married my fifth grade sweetheart [Henriella Mylar], and we were expecting our first child, Michele. We had both enjoyed growing up in Huntington and felt it would make a fantastic place to raise a family. So we decided that the quality of life was most important and accepted a job with a firm in Huntington.

REYNOLDS: For whatever reason when you are young, you think that to retire early is success. But of course that’s a big misnomer. Eventually I came to realize that money really only has one value and that’s insulation -you don’t have to be involved with people you don’t want to be involved with, you don’t have to do things you don’twant to do. I had said when I was 35 that I was going to retire when I was 40. And the most enjoyable place I had ever been to on vacation was Hawaii. One summer, I tested what retirement would be like and to be honest with you, I was bored to tears. I had also thought that so many people in West Virginia had the potential to make it and perhaps I could be of some help to them. As Mike once said, “It’s kind of like going up in a tree house and pulling up the ladder.” So I thought I could make a difference and chose to stay.

HQ: At what point in your careers did you decide to start giving back?

PERRY: I remember one day Marshall said, “Isn’t it time we quit bitching and complaining. We’re sitting up here in the stands. Why don’t we get down on the ball field and take three swings at the bat. We might strike out but we may get a single, we may even get lucky and get a double.” So we didn’t start out with the intent of making a lot of money. I took what turned out to be a $50,000 pay cut to leave the law practice and to get into banking. I’ve more than made it up but it wasn’t a financial thing. I think we both believed that banking was a method by which we could accomplish some things and make Huntington a better place to live and create opportunities for our children and their classmates. We both were concerned that we were losing a lot of young people because there weren’t any jobs. And that really was the driving motive – to make some things happen. But, you can’t just do it with a bank. You have to have an educational system, recreation, cultural, medical, infrastructure, etc . … and you have to show a compassion and concern for others. We generally haven’t tried to do the same things together. I think Marshall has done a fantastic job for the United Way, the Boys Club – his love and compassion for children, particularly disadvantaged children of all races and creeds, is second to none. I have worked a lot in education. I’ve tried to spend some more time in the cultural areas. So we’ve really tried to compliment each other to where we’re dividing it up, although we’ve never sat down and consciously gone over it.

REYNOLDS: My father always told me that it was very important to leave everything better than when you found it. And I have made an effort to do that from the very beginning.

HQ: Your work schedules are grueling. You each put in 10, 12, 14 hour days and yet still find time to get involved in an array of activities. How do you do it?

PERRY: I think people find time to do what they think is important. I know that Marshall is not a golfer, he doesn’t play tennis, I don’t think I’ve ever seen him on a boat, I don’t think we’ve ever gone hunting or fishing. There’s nothing wrong with any of those activities – I used to play a great deal of golf until at bonus time I realized that Marshall never asked me what I had done to lower my golf score. So I learned to not worry so much about my golf score and worry more about earnings per share increases. So you just simply prioritize your time. We only work about a half a day and what you do with the other 12 hours is really up to you.

REYNOLDS: All along I have prioritized things. I spent 99 percent of the evenings with my two boys as they grew up. That was a priority for me. I like to start early and ‘at the end of the day, put a line through what I’ve done. And I think it’s very important that you work at completing things. You know a lot of people get up and go to work everyday and work at something and never complete anything. I really don’t have that much trouble finding time. Lord, you can find time. The question is, “do you want to do it?”

HQ: What have been some of Huntington’s greatest successes and failures in your lifetime?

REYNOLDS: Some of the greatest failures have been the apathy when the lawsuit was brought to stop the building of the mall at the 16th Street exit. That probably would mean $1 million today in the city coffers. That probably would mean a solid retail base down through 16th Street, making a left down Third Avenue. I think one of the failures was not running the interstate through the city.

Certainly the closing of Owens-Illinois has to rank as one of the top failures. Andi think we have to look at that and say, “Why Huntington? Why one plant out of 25?” Stop and ask yourself this question: Kerr Glass had 2 5 plants and closed the one in West Virginia and now they have 24. Owens-Illinois had 25 plants and they closed the one in Huntington, West Virginia, and now they have 24. Well, why did they pick Huntington? Why did both those companies pick West Virginia? And the answer is a combination of Worker’s Comp [Compensation] and other hassles from the government. Those have been our failures.

HQ: What can we learn from those failures?

REYNOLDS: We have the problem -this is the single-most important thing I am going to tell you – instead of trying to fix the problem, we try to fix the blame on some body or some thing. Whether it’s the economy, whether it’s switching from glass to plastic … we really don’t address the problem, we just try to address the blame. We need some real investigative reporting on why this happened, how it happened, when it happened and then learn from that and go forward. Remember that. We work awfully hard to try to fix the blame. I’ve heard so many green weenie explanations of some very simple things – of how Jack Houvouras’ third cousin did this and it’s all some big ulterior program. I mean Alfred Hitchcock wouldn’t go that far. Fix the damn problem. The hell with fixing the blame.

Some of our greatest successes? I think you have to include United Huntington Industries [UHI] which Dr. Tom Scott led – you had some folks from three or four different “clans” or “clicks” pool some resources together. I think KYOWVA Corrugated Box is a good example where the seed capital came totally out of local pockets. I think the First Huntington National Bank, which was the pillar of Key Centurion Bancshares, which became the number one financial institution in the state – I think that’s been a pretty damn big success for Huntington. I think Steel of West Virginia – they were closing it up and some local guys rallied together and raised $1.5 million to re-open the plant. I think it’s very important to remember that Bob Bunting had a vision and stayed in there and led the charge. And, I think it’s important to remember that those folks who put up that seed capital were blessed with a ten-fold return very quickly. We’re talking about 600 jobs over there. That’s got to be one of the biggest successes in my adult life. All we need is ten more like that.

PERRY: I think we need to learn from the past but if you’re going to dream you’ve got to look forward.

One of our failures – if you look back, this was an exciting distribution area, a wholesale center of the area, and we failed to realize that people had to have modern roads to get here. And other people did a better job figuring out how to get the roads into their communities. That was one of our tragic mistakes. But perhaps the one that would concern me most is that in the 1960s and early 70s we failed to recognize that the world was changing and many older companies in the area were having difficulty coping with technological changes in their industry. For example, we lost Houdaille Industries not because they didn’t make a good bumper, but because the auto industry wanted plastic bumpers, not heavy steel ones. As a result of these changes, we lost a lot of our young people as well as retired people

who took what they had accumulated here and moved south. It’s nice now to see us trying to become a retirement center. We lost the young and we lost the affluent older and we didn’t realize what we were doing to ourselves and our future.

As far as our successes, I think we are exceedingly fortunate that Marshall University is no longer just a teacher’s college and is truly a university. Also, there is the advent of the medical school here and the tremendous growth of the medical community and what that’s meant to the quality of life – the fact that we have things like neonatal intensive care, burn centers and open heart surgery and two very large significant hospitals. We have an outstanding museum, the riverfront … it’s very exciting. I think those things will serve us well into the future.

HQ: In 1970, Huntington’s population was 74,315. In 1980, 63,684. And in 1990, 54,800. What has gone wrong in the last 20 years?

PERRY: I think during that time we have lost in excess of 10,000 manufacturing jobs, and that’s the answer. Those men and women had to move away with their children and seek jobs elsewhere. If you lose 10,000 jobs, you probably lose 30,000 to 40,000 people. As for solutions, what we need to do is go back and see what Huntington was like in 1900, what it was like in 1950 and then ask ourselves what will Huntington be like in the year 2,000.

The year 1950 was probably the zenith for Huntington as our companies were at their height after the war. We were also the wholesale distribution point for the region. We were on top of the world. Like many communities we thought things wouldn’t change, but they did. If you study history, you know that nothing is static – everything is constantly changing and I think our leadership failed to see that. But there has also been a wealth of positive change since 1950 – the interstate system, the airport, the health care field, Marshall University and its med school. A lot of positives. But, we have not been able to replace those industries that are 70 or 80 years old. How do you replace the traditional heavy manufacturing jobs like steel, chemical, glass with new modern jobs? I think what we’re doing with the Chamber of Commerce, Huntington Industrial Corporation [HIC], HADCO [Huntington Area Development Council] is part of the answer. And obviously I think it’s exciting to see the community come together at these town meetings sponsored by the paper, the television station and the university. It won’t be easy, but it’s an important start.

REYNOLDS: The answer is economic development. If you really analyze it, everything that has been tried in economic development over the years has worked. So when you ask, “What went wrong with this census?” the answer lies in the fact that we haven’t tried enough [in economic development] or loaded the same gun and fired again and again and again. Mike makes some good points about history and change.Yes, our leaders failed in the 50s to pick up the change, and in the 60s they still hadn’t picked it up. In the 70s they finally recognized what was going on. But, as a group, we have not reinvested in our community and we have not reinvested in business. And that’s what creates opportunity.

HQ: The word on the street is that West Virginia’s business climate isn’t very friendly. What needs to be done to turn this around?

REYNOLDS: Well, the business climate by and large isn’t very friendly.

HQ: An example?

REYNOLDS: A very obvious example is this terrible Worker’s Compensation program in West Virginia. Worker’s Comp has basically been turned into a welfare system. It was designed to take care of people who are hurt, but it is greatly abused and the price for it is extremely excessive. What we need to realize in this state is that business is like a three-legged milk stool as my old great uncle used to say – it’s capital, it’s equipment and it’s people. As you look for a balance in business, you’ve got to have all three legs of that stool.We have an abundance of people that are willing to work and are very capable leaders. Obviously, if you have the right people and you have the capital, getting the equipment is really not a problem. But our businesses, for the most part, are undercapitalized. So we’re trying to balance a stool in this region on one leg.

PERRY: When Marshall first talked about the three-legged stool, he described it as capital, people and “a dream.” I think he included equipment as part of capital. People come in with a great idea. But I think the majority of people don’t understand numbers.

REYNOLDS: In general, our people are the best. A fellow who was running a plant out in California said to me, “It’s real funny. In California, if you have a factory with 100 people, 80 will be very average and the other 20 will be outstanding.” He said, “In West Virginia, if you have a factory with 100 people, 80 will be outstanding, 10 will be average and another 10 will be terrible – they will want to agitate, cause a strike and foul things up.”

When we look at the guys who sold their plants or quit or hung it up, they probably had faced this and said, “the hell with it,” and moved to Florida. They probably got tired of dealing with the unions and liquidated their plants and left. We have a “run it or ruin it” mentality that spills over probably from the coal fields. It’s a philosophical position that a lot of folks have here in Appalachia. It doesn’t matter if it’s a business, or the chamber of commerce, or the bank or whatever, “as long as I’m running it it’s good, and if I can’t run it, I want to bad mouth it.” We’ve seen that over and over again on a lot of different fronts. And that’s a pretty tough situation that we must overcome.

PERRY: What we’re talking about here is what Marshall refers to as the “Crab Theory.” The Crab Theory states that if you put a bunch of crabs in a bucket, none of them get out because as sure as one reaches the top, one of the other crabs grabs it and pulls it back down. So you don’t have to put a lid on a crab bucket because the crabs themselves will make sure that no one escapes. And we as human beings have that same attitude. We don’t work cooperatively to create a stairstep, so to speak, so that people can get out and when they get on top, reach down and pull the next guy out. Everyone gets out of the bucket if we all work together.

REYNOLDS: Can we turn it around? Sure. All it takes is some commitment. You can accomplish anything if you don’t care who gets the credit. The problem is there’s always someone who wants to get that credit and most of those folks are in public office. [Laughs]

Certainly we’re all familiar with the fact that there is a lack of investment capital in our region. So, as we get our more successful citizens – whether they were born out of the bucket or were able to climb out- these folks have a tremendous responsibility to invest in new businesses. Finally, what we need to do to turn it around is for people to understand- to teach and not to preach. When I was in elementary school in west Huntington, we had one 40 minute lecture on what capitalism was. That’s it! I went on to Vinson High School and never heard it [capitalism] mentioned once. Now we did have a strike organized at Vinson High School because Wayne County didn’t go on daylight savings time and Cabell County did. But you see our people don’t understand what it takes and most of the people are pretty naive from a capitalistic standpoint. It’s understanding, understanding, understanding. What in the hell does it take? And it takes three things to make it in business.

PERRY: If you look around the world, you see a number of former communistic countries coming toward us wanting a democracy. I think the truth of the matter is they’re not necessarily wanting a democracy, they’re wanting the quality of life that we have in America. And that’s not simple because we have a democracy. Other countries have democracies. What makes America great has been not only our democracy and our public education system, but our capitalistic, free enterprise system. We spend a lot of time talking in schools about democracy but you can get through 12 years of school, four years of college and probably three years of post graduate work and never hear the words “capitalism” or “free enterprise.” And until you do and until the general public understands what creates a job, we will never know what it takes. You won’t elect representatives who understand and so consequently nothing changes. I think that’s why what is going on with the town meetings is hopeful.

HQ: It’s an important first step.

PERRY: Yes it is because we don’t have time to wait for every kid to go through school.

REYNOLDS: Think about one thing. When I was a boy, we had mayors like W.W. Payne, Cecil Thompson, Bob Steele -you had business leaders as mayors running the town. Then we went to a city manager form of government. When we went back to the mayor form of government, the three original candidates were Bobby Nelson, Chuck Polan and Ted Barr. Basically, you’re looking at three political people that had a political following and a political base. So what happened is our business people said, “The hell with it. We don’t want to get involved in that.” Something has gone wrong. We’ve gone from making a business decision to making a political decision. Not enough of our people, and certainly not enough of our politicians, really understand business. And business is what makes payrolls which is what buys cars and puts bread on the table. If we grow that, we grow everything. It’s pretty damn simple.

HQ: What then, ideally, should be government’s role in business?

REYNOLDS: Government’s role in business should be to provide the infrastructure, whether it’s police, fire, support. They should do everything they can do to support business. That’s exactly what government’s role needs to be.

PERRY: Governments weren’t formed to take care of businesses. Governments were formed to take care of the collective needs of the people in a more efficient manner. And business is just a part of that. They need the same infrastructure that the people do and are willing to pay their proportionate share. But there’s got to be some correlation between the cost of providing and receiving government services and we’ve gotten away from that. We now expect business to pay the vast majority of it. But it won’t work because then you choke those businesses out and no one else wants to come in and pay that type of cost when other states and countries will welcome them with open arms for less.

HQ: If you could change three things to improve the business climate in West Virginia, what would they be?

REYNOLDS: The “run it or ruin it” mentality, Worker’s Compensation and Unemployment Taxes.

PERRY: I think if l could just change one thing it would be to recognize the interdependency of us all – government, labor and management together. I think the average citizen needs to understand the free enterprise system. There is no free lunch. If you’re going to give something away, somebody has to pay for it. A perfect example is the fact that we don’t want any elderly person on a fixed income losing their home because of high property taxes. So, we came up with a Homestead Exemption. It’s a great idea. Now though we have one out of every three or four properties in Cabell County exempted. Those taxes have to be paid by someone. And so all of our good intentions are very expensive until we have more people to pay the taxes.

We need to understand the tax system. We need to understand the consequences of our generosity. As the old saying goes, “You can’t have champagne taste on a beer budget.” I think we have to realize that the sacrifices that are necessary to change the future of Huntington and the state of West Virginia have to come from everybody – not just from the rich, not just from the corporations, but from every man, woman and child in the state. West Virginia is a great place to raise a family, it’s a great place to find ingenious, hard-working people, but companies have to make a profit. And so they want to know, “What are my corporate taxes, what are the local taxes, what are the indirect taxes like Worker’s Compensation and Unemployment Compensation?” So I think we have to create an atmosphere where school teachers, the media and the man on the street recognize the importance of business. Because in the final analysis business men and women create jobs, not government.

REYNOLDS: Let me tell you a funny story. Mike was just talking about the Homestead Exemption. My Uncle Curtis is 78. He’s been retired from the IRS now for 23 years. He got a $14,000 a year pension when he retired and today it’s $40,000. Like most people his age, his home is paid for and he doesn’t have a car payment. He was telling me the other night that he has been quarreling with the state over his taxes. They finally acknowledged that he doesn’t have to pay any state income taxes because he was employed in law enforcement. So we look at all of this and we see that he doesn’t pay any state income tax, he has a Homestead Exemption, he likes to fish and gets a free hunting and fishing license [Laughs]. And that’s great but he says to me, “This world is crazy. Now that l can pay my way without putting a strain on my wallet -because I have a good retirement plan – everything is free! I am in a position where I could afford to go anywhere I want on vacation. If l want to go to Europe, I can. And if l go, everything is free.”

HQ: And we’re all paying for it.

REYNOLDS: And we’re all paying for it. That’s exactly right. Mike makes a good point when he says you can be 66 years old and still be working and get that exemption [Homestead Exemption].

PERRY: Or have a million dollars! It’s almost like a lottery – a “something for nothing” mentality.

REYNOLDS: Let me give you an example. For a long time I’ve wanted to be a teacher and I have been fortunate enough to teach several Junior Achievement classes over the years. I would always begin on a Monday morning by asking, “How many of you kids want to be millionaires?” And if you had a class of 30 kids, 28 would raise their hands. So I used to go around the room and ask how they were going to do that. One of the kids would say, “I want to be a doctor and if l work hard … ,” another would say, “I want to be an engineer and maybe I can end up being president of DuPont,” or another would say, “My Dad said I did a great job selling candy for the Boy Scouts so I am going to be a salesman.” The last two classes I’ve taught, when you ask that question 80 percent of the kids will tell you they’re going to hit the lottery. [Laughs] And it’s carried over to our legal system in West Virginia. I mean every one of these damned lawyers are out to find the case where they can hit the lottery and get something for nothing. So we’re beginning to permeate into our attitudes this “something for nothing” idea. If we’re going to make a lot o.f money, we’re going to do it by making a dollar everyday. We’re not going to do it by making a million dollars overnight. It’s not going to happen. We do have a lottery mentality in West Virginia.

HQ: I wander how we got it?

REYNOLDS: Well, one of the ways we got it is seeing these lottery ads on television and reading these stories about ol so-inso who got a judgment because somebody hurt his feelings at work. We’ve lost our pride in productivity.

PERRY: We’ve got the same problem in economic development. Everybody wants that new manufacturing company that’s going to employ 1,000 people. And we really would be better off having 50 new companies employing 20 a piece. That’s the same 1,000 but it’s much more diversified. We’ve had those companies but it’s just that we have a tendency to celebrate our failures rather than our successes.

REYNOLDS: We do celebrate our failures. Certainly Owens-Illinois is the biggest celebration that we’ve had since probably 1970. We need to start having some homegrown industries – some people who use nickel or some people who use steel. Portee [a local manufacturer that produces railroad components] is a good example of a new company. If Steel of West Virginia wasn’t here, you couldn’t have had a Portee. There’s no reason for it being here except for the fact that they utilize that raw material. Yes, Owens is a great failure and we all need to participate in it and we need to examine it but Steel of West Virginia is a great success. I mean Bob Bunting ought to be put up on pedestal for his vision. But how can we build on more of these things?

PERRY: There are many of these small success stories and the cumulative effect is significant – if a lot of these successes hadn’t occurred, our population would be down to 20,000. So, we have replaced part of the loss. But we’re wanting to replace it with jobs that enable people to have an opportunity to take care of their families, buy homes, educate their children. And that really takes more than a minimum wage job.

HQ: Everyone is talking about economic development. How should we be approaching it?

PERRY: I think we have been guilty in the past of just shooting with shotguns and going in a helter-skelter manner. But I think now we’re becoming more singleshot, asking ourselves, “What type of industries would find Huntington, West Virginia most attractive? Which ones would be attracted by a medical school, a university, quality medical facilities, recreation, culture and work force?” Then we need to go after them. We must work smarter, not necessarily harder. But we’re going to have to work harder and smarter because we’re behind. We haven’t accomplished everything we would have liked but look at the Huntington Industrial Corporation [HIC], look at United Huntington Industries [UHI], look at the people who are investing in downtown Huntington who are local people. It’s exciting to think we may have another shot with an interstate – Interstate 73 to make Huntington more easily accessible from southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky as opposed to everything having to go to Charleston. Route 2 being expanded, river ports, a regional airport … At least we’re beginning to aggressively try. I don’t want you to think that we’re despairing. I think we’re discouraged, we’re frustrated but I see great things for the area. But they’re not going to occur as fast as we would like.

REYNOLDS: The thing we don’t understand more than anything is the type of job we create. You know if Huntington Plating [the Houvouras family business] doubled its employment with an expansion, then are you creating jobs with Heiner’s Bakery? Yes. Are you creating a job with a local bank? Yes. But, if we go out and create another retail store we’re just dividing up the pie. So, if we open up another restaurant, yes we’ll have 15 employees but Shoney’s will lose five and Oliver’s will lose two. There needs to be a manufacturing and distribution base. That’s what makes the damned fuel go.

HQ: Many of the people who have worked in economic development in Huntington have complained that there just isn’t enough marketable land for industry, in particular, industrial park sites. What can be done?

REYNOLDS: If you go out to Prichard, you’ll see you’ve got an awful lot of land. So what do you need with more land until you fill that up? On the east side of Huntington [Route 2] you have significant potential for industrial development. When we look around at the land, there’s plenty of land across the river. We can develop our region and the whole secret to it is that Huntington, Ashland and Ironton are in bed together. These rivers that run through here are kind of like big walls. So, there’s plenty of land. Remember this – every location has some strengths and every location has some weaknesses. That’s bull about the buildings and about the land. We can accommodate them.

HQ: What about infrastructure -businesses say they have had trouble getting sewer, water, roads, etc. extended to their property?

REYNOLDS: If it costs money, the government has trouble doing it. But remember, those guys [ the government] are dealing with a budget. They’re not dealing with a cornucopia of funds.

PERRY: I think transportation and access are important and that’s why we were talking about how important it is to have Route 2 expanded and have access to I-64 and to have I-73 and to expand Route 10. All of these things are important. There is no single thing that can be done. All of these things have to happen. We made a trip down to Huntsville, Alabama, and they taught us a lesson that we’ve never been able to apply. The businesses, the government leaders, the labor leaders and all the people down there said, “We’ve learned how to work together. If we think there’s a new project in Washington, D.C., labor and business and government all go to Washington enmasse in total agreement that we want this. Once we get it, then we fight like cats and dogs amongst ourselves as to how we’re going to divide it up.” Our problem is that we aren’t unified. Back to Marshall’s reference to a three-legged stool – government can’t do it without capital, business can’t do it without government cooperation and labor doesn’t have jobs if the other two don’t come through. We’ll win when we are all together saying, “We want you here in Huntington. We need your company and we’ll tax you a reasonable amount because you need to pay your fair share.” And business is happy to do that. But business wants to make sure that they have an atmosphere where they can compete with their competition – who are the other guys trying to put you out of business. Therefore, business expects the city, the government, the local people and the employees to be on their side.

REYNOLDS: Let me make an important point. We need to create an awareness. A few years ago I was out raising money for an economic development project and called on a local manufacturer. I told him he needed to give some money to this deal and he said, “Marshall, when you cut through the crap I can see why all the banks are paying, I can see why Heiner’s Bakery is paying. If we get 100 new jobs, the banks are going to get some new checking accounts, Heiner’s will sell some more bread, but the only thing I’m going to get out of it is somebody else competing with me for my people.” And he really, sincerely believed that. And I said, “O.K., let’s suppose all these businesses go through a normal attrition and you’re the last business in Huntington and you don’t have to compete with anybody for labor. Then you’re the guy who has to pay 100 percent of the taxes.”We need more businesses because that’s what shoulders the tax burden.

PERRY: That’s it in a nutshell.

REYNOLDS: And when I said that, he told his secretary to give me a check for $1,000. Stop and think about that. You can see where the banks had some instant gratification. But everybody wins. Heiner’s will win, every retailer in the market will win …

PERRY: And the retired people will win because there will be some body who wants to buy their home …

REYNOLDS: The school board will win …

PERRY: The school board will win because there’s going to be more taxes. Everybody wins. Unemployed people win because then we have more money in our till to take care of our social conscious.

I have learned to appreciate the importance of money, or as Marshall calls it, “insulation,” and I realize that you can have social concerns, you can have compassion, but if you don’t have the finances to take care of these things -you have to have some prosperity in a community in order to do all the things we want to do. HQ: How do we change our poor business climate?

REYNOLDS: Awareness. Awareness. Awareness.

PERRY: The people, the voters. If Marshall and I go up and see the governor and talk about big taxes, he can’t change things by himself. And the legislature can’t change things unless the people want it. All of that is a reflection of the average voter and until they have an appreciation of how the system works, it’s not going to change.

HQ: We’ve identified what some of the negatives are of doing business in Huntington. What are some of the positives?

REYNOLDS: The labor force. The labor force is a big positive. The quality of life in this town. The cheap housing. I mean you can get a great home is this town very, very reasonably.

PERRY: Quality education. The medical facilities. Low crime. I was speaking with Police Chief Gary Wade the other day and he mentioned that we only had two murders last year and neither one of them were drug-related.

HQ: What do you make of the tremendous turnout at these town meetings? PERRY: I think the loss of Owens-Illinois has crystallized us to action. I think people from all walks of life are coming to the table and saying, “What can we do?” And I’m a firm believer that as people become better informed, they will see that there aren’t any simple answers but working together we can get the job done.

REYNOLDS: As I said earlier, the answer is awareness. The Huntington newspaper, as well as one of the television stations [WSAZ Television 3] have joined in to create an awareness. So the people are responsive because they now recognize the problem. To the media’s credit, they have endeavored to act as a catalyst, which is the responsible thing for them to do – which, quite honestly, hasn’t taken place until very recently.

HQ: The image of Huntington, in particular its self-image, is said to be a major stumbling block to unlocking our potential. How can we foster a stronger self image?

REYNOLDS: The first thing we need to do is figure out why we lack self-respect, why we have this poor self-image. And, the reason we probably do is because we’ve shot ourselves in the foot a number of times. We’ve kind of suffered in silence when we’ve seen these things happen. Also, we have been told by the national media, be it Life magazine’s old story about us poor, dumb, barefoot West Virginians or whatever … and we get this beat into us as youngsters. We talk about this Montani Semper Liberi [Mountaineers Are Always Free] and yet we have fifth generation people here who are on welfare now. We’ve kind of lost that old self-sufficient pride and we’ve been with the system and bent our pride to take something for nothing. It’s really beat the hell out of our self-image. How can you change that? How can you reverse that? Obviously you have to have some economic successes. We have to work together to get out of the crab bucket. Remember, everything that has ever been tried from an economic development situation has worked here. So, you just have to try more and more things and play off of other people’s creativity and ideas and not be afraid to dream. You know there is a phenomenon among our people – if you had an idea for a new chocolate ice cream cone and presented it to ten people, all ten would tell you why it wouldn’t work. If we could just discipline ourselves to think for 30 seconds before we express something negative to young people who are at the apex of creativity, and offer a little encouragement instead of criticism, we’d probably go a lot further.

PERRY: Marshall, give him your definition of happiness.

REYNOLDS: The happiest time in a young man’s life is when he is in hot pursuit of a buck with a reasonable chance of overtaking it.

PERRY: Now, when he told it [definition of happiness] to me, he didn’t say “a buck.” He said “a dream.” I think happiness is having a dream and having some reasonable hope or expectation of achieving it.

REYNOLDS: Now Mike you change it [definition of happiness] depending on who you are talking to. [Laughs]

PERRY: I think you need to dream. I think we need people to encourage us, foster us and help us. I think that’s where Marshall has been the greatest mentor for many. But, that’s also why we have school teachers and parents. I think that’s how you change perception. If you tell a child every day that he or she is stupid and has no talent, it’s very difficult for that child to grow up and reach their full potential. The same is true in Huntington. We need to start celebrating our victories and our successes instead of sitting around constantly belittling ourselves and our past problems. Everybody has had difficulties in the past. But real character is how you pull yourself up and go forward.

HQ: You have both traveled extensively during your careers. From what you have seen, what are other cities doing right?

REYNOLDS: The one thing they seem to do right is somebody has a vision and sells some folks on it and in that community they all march to the same drummer. Huntsville, Alabama, has to be a wonderful example of that.

PERRY: I’ve had the opportunity to visit many thriving communities but in each one of those places, there were also ugly aspects of the community. I always come back thinking how fortunate I am to live in Huntington, West Virginia. We have the lowest crime of anywhere in the country. We have our problems but it is still one fantastic place to raise a family and instill in them the values and principles that have been so important to our country- if we can just make sure people have good jobs. And that’s a lot easier to solve than to be in some of those cities trying to figure out what they need to do to solve their ghettos, murders and divisiveness. We have problems but so does everybody else. I think our problems are solvable. I’m not so sure everybody else’s are.

HQ: What’s your take on the proposed regional airport? Is it feasible, is it going to help us and, if so, where should it be built?

REYNOLDS: Yes, it is feasible. Yes, it will help us. But you have to get the community to work together. It doesn’t matter which site we choose. Let’s just pick the one that offers the most advantages to all the cities. Let’s pick one that offers a balance of good for all and everybody get behind it and get it done.

PERRY: I think this is an extremely important issue that’s not well understood. Each of us [Huntington, Charleston, Parkersburg] have a reasonably good airport but we’re talking about airports of the future. While I understand how convenient the Charleston airport is to that city, I also understand that we have to look at the proposed regional airport as a major conduit to economic development. This airport will enable new industries, like down in Huntsville, to be serviced. The airports in Huntington, Charleston and Parkersburg are adequate today but we need to talk to experts to see if those airports will be adequate in the future. I think their answer will be no.

We’ve had the tendency to say, “We’re fine today,” and not look ahead and ask ourselves if we’re investing for our grandchildren.

HQ: If tomorrow a suitcase was delivered to your office with $1 million in cash and a note attached that read, “Use this money to help Huntington,” what would you do?

REYNOLDS: I’d find somebody that had an idea and invest in a business they were starting or some existing business that wanted to expand. I would try to use the money as seed capital to create jobs. Now 30 years ago I would have probably given the money to the Boys Club or the United Way and once they did what they could do with the money, it would be gone. But if we have jobs and if we have companies that are paying taxes, the good that comes out of that goes on forever. And once those companies cease, it just dries up. So, that’s what I’d do.

PERRY: I would probably …

REYNOLDS: Mike would probably count the money four times. [Laughs]

PERRY: I would probably be inundated with people who all had good ideas as to what to do with that million dollars. But in the final analysis, I agree with Marshall and would invest the money with some- one who would create jobs. Marshall calls it the “seed corn.” What we’re talking about here is the “seed corn” in the form of a million dollars and we’ve had a tendency in the past to eat the “seed corn.” What we’re saying is that it needs to be put back into the ground.

HQ: You both have sons that are close in age who are part of the next generation that will inherit Huntington in the 21st Century. Ideally and realistically, what would you envision for them should they choose to stay in Huntington?

REYNOLDS: I’d like it to be a vibrant economic area where there is not only a spot for my sons, but there’s a spot for their friends. I’d like to see our region quit exporting our youth and provide some opportunities for these youngsters where they can enjoy the quality of life that we really have. We do have a hellacious good quality of life. If you have a job here that pays a reasonable living, then you can enjoy a very good standard of living. I’d like to see that spread over more and more people.

PERRY: Looking back, I thought Hun- tington in the 1950s was a great place to grow up. When I graduated high school I could have gone to work at any number of manufacturing jobs that would have given me enough money to have bought a home, raised a family and educated them. Many of my classmates did that by working at INCO or CSX or Owens-Illinois. They had good jobs. We also had a choice of going on to college or into the military where you could make a career. There were a lot of good, solid choices. That’s what I want my children, their friends and everyone to have – choices. I think that’s what we all dream for.