Has history forgotten Jackie Hunt?

By Ernie Salvatore

HQ 19 | AUTUMN 1994

It was a time of innocence, mingled with anxieties and hope. War clouds had darkened Europe. Japan was building a military machine, not motor cars. In America, the Great Depression was peaking. A quarter bought a pound of steak, new cars sold for $600 and FDR told us we had nothing to fear but fear itself. Movies, big bands, radio, baseball and college football were our only refuges. They gave us heroes we could seldom touch and rarely see up close in the flesh.

One such was John Seva Hunt, who grew up on Huntington’s Latulle Avenue, the third son of a railroader. He became, in the eyes of many, the greatest complete football player in the history of Marshall University, and one of the best anywhere. This is his story.

On November 21, 1940, a cold, gray, Thanksgiving afternoon that nevertheless saw close to 10,000 spectators crowded into the stands at old Fairfield Stadium, Jackie Hunt set a new NCAA single season record by scoring his 27th touchdown. The last of four he turned in that day to lead a season-ending 67-0 rout of West Virginia Wesleyan, it was one more than the old mark held by Virginia Tech’s Jimmy Leach. Hunt’s remarkably resilient record resisted challengers and the advent of free substitution rules for 31 years. His four touchdown finale also rewarded Hunt with another dividend. They crowned him king of NCAA’s scorers of 1940, still a first in Marshall athletics. His 162 points beat out such Hall of Fame All Americans as Michigan’s Tom Harmon and Texas A&M’s John Kimbrough.

Huntington, quite unnaturally, discarded its usual inhibitions and went ga-ga over its hometown hero. On the Marshall campus the victory “bell” – actually a cast iron I-beam – clanged far into the night. Why not? Jackie Hunt had put tiny little Marshall College – then all of 1,800 students strong – and big, bustling Huntington, on the national sports map.

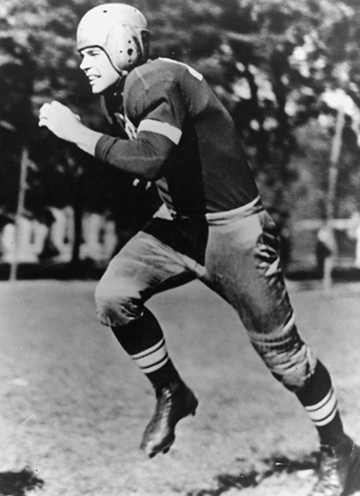

Unfortunately little of this is remembered here today, save for a few survivors. Time, the 1969 recruiting scandal, the plane tragedy and the subsequent dawning of a spectacular new football era have conspired to diminish Jackie Hunt’s stature. Sooner or later it happens to everyone, unfortunately. It’s the downside of history. True, there is a picture of Hunt with a minimal identification line and no career profile in the Marshall Stadium press box. The same picture appears in the press guide where he’s given brief, homogenized mentions in the various career categories. Otherwise Jackie Hunt, once one of the most celebrated backs in America, has been consigned to oblivion, pushed aside to make way for the present.

Ah, but there was a time when the name Jackie Hunt was synonymous with college football, pre-World War II style. A blue collar style of strength, stamina, speed and versatility. His name and picture kept popping up everywhere. Coast to coast. In newspapers. In magazines. In newsreels. He was a prototype college football hero of the ’30s and ’40s. Tall, handsome and oh so terribly shy, he attracted females and assorted admirers as easily as light does moths.

Today he’s become a question.

“Jackie Hunt?” this magazine’s bright, young editor-publisher asked when I mentioned the name. “Jackie Hunt, Jackie Hunt,” he repeated ever so slowly. “I never heard of him,” he confessed. “Who IS Jackie Hunt?”

“Ask your father, ask any sports fan over 65 in this old town and around this part of the country,” I advised him gently. “They’ll tell you there’s never been another player remotely like him at Marshall. Probably never will be. Today’s rules prohibit it.”

Silence usually greets these expositions. I’ve encountered that silence countless times.

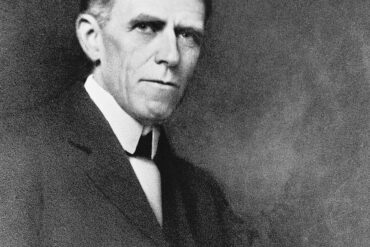

But, believe me, Grantland Rice, the late dean of sports journalism, would agree. If Granny – the John Madden, Dick Schaap and Bob Costas of his day, all rolled into one – anointed Hunt one of the 10 best backs in America in 1940, which he did, then he was one of the 10 best backs in America – an agile 195-pound, 6-0 foot, power running, 10 second fullback in the days of cinder tracks and spiked shoes. As was the custom in that limited substitution era, he had multiple duties, doubling as a halfback, tripling as an end, punting, playing linebacker and cornerback on defense. The two-platoon system and fractional role players were unheard of.

“For all-around ability,” Granny wrote in Collier’s magazine (one of the leading magazine’s in the pre-TV era), “I doubt that there is a better back in America than Jackie Hunt who with a better schedule might easily have been another Harmon or Kimbrough.”

“Hunt,” Rice continued, “can do more different things better than any other back – ball carrying, kicking, passing, blocking and tackling, but the opposition wasn’t testing enough for an All-American. This is no fake ballyhoo for Jackie Hunt, whom I have never seen. But when Doc Spears, coach of Dartmouth, Minnesota, Oregon and now of Toledo, adds his testimony, you have to listen. Doc Spears doesn’t believe there’s a better all-around back in America. And he has no exceptions. ‘One of the greatest,’ is the Doc Spears tribute.”

So, Granny struck a deal with Hunt’s allegedly soft schedule that included Virginia Tech, Toledo, Wake Forest, Dayton and Cincinnati Xavier, every one a genuine major opponent at the time, and awarded him a rare special mention on his All-American team as well as a first team Little All-American.

The late Dr. Jock Sutherland, Pitt’s all-time Hall of Fame and Rose Bowl head coach, was another Hunt booster.

“We wanted him at Pitt,” Jock said. “Hunt was the best high school back in America in 1937.

Big, fast, passer, ball carrier and kicker, loaded with exceptional football talent. But Hunt wanted to stay in his hometown. He felt that Huntington was where he belonged.”

Not surprisingly, Jack’s reputation drew more than two dozen scholarship offers, an unusually large number in the 1930s. News didn’t travel as fast. Coastto-coast air travel was in its infancy. Television, a pipe dream. But hometown Marshall led Hunt’s list, followed by Pitt, Ohio State, WVU, Duke, Alabama, Notre Dame, Tennessee, Kentucky, Florida and Colgate. Recruiters swarmed around the Hunt family home like locusts and pestered him at school, where he was an all-stater in track and a member of the Pony Express’ state basketball champions.

“Leave Huntington?” Hunt often said. “Never. This is where I was born. This is where I’ll end up. This is home. So why leave?”

He didn’t. He chose Marshall and “The Legend,” Cam Henderson. His decision clogged the headlines and the airwaves. The fans in Huntington and the Tri-State, used to seeing the area’s finest athletes go elsewhere, were ecstatic. One group of Huntington businessmen was so overjoyed its members took out a $10,000 insurance policy on Hunt. That translates into $250,000 in today’s money. He repaid them in full.

Despite his notoriety, however, fact and fiction quickly became Jackie Hunt’s lifelong companions. Whether he saw them as curses or blessings we’ll never know, but they did create a legend that stuck to him long after he swapped his football uniform for the joys of privacy and marriage to the former May Gillette. The spotlight? Celebrity? These weren’t his natural venues. They made him uncomfortable. Unlike the “Hey, look at me” hot dogging that prevails today, he preferred to have his exploits speak for themselves, right up to the moment he died, quietly, far from the cheering crowds, onJune 19, 1991.

And there’s the rub. Instead of leaving behind a glittering statistical index of his football exploits, he left suppositions mostly. It was no fault of his own but simply Hunt’s bad luck that most of his career records weren’t preserved in Marshall’s primitive sports archives. Instead they were to be forever muted by shabby record keeping, incredibly imprecise sports writing, and Cam Henderson’s paranoia for secrecy.

Henderson disliked the star system, yet here he was coaching one of the brightest stars in the country. Neither did he believe in the meticulous recording of individual statistics that we see today, yet here he was coaching a player who, presumably, was establishing NCAA standards that would have stood the tests of ages. Estimates are that Hunt was college football’s first 3,000-yard all-purpose man!

Compounding the problem was Marshall’s nearly non-existent sports information office, a void Henderson preferred. This further beclouds Hunt’s records. Consequently, it was only logical that fact and fiction would surround Hunt and dozens of his talented teammates, many of whom, like him, had NFL futures. Henderson’s genius notwithstanding, marketing his assets wasn’t part of his coaching philosophy.

Still Marshall’s spotty record books of that period do manage to impart a few Jackie Hunt snippets. For example, in only three seasons, 29 varsity games and a 24-5 won-loss record-the freshman rule and 10-game schedule limits in effect – he scored 43 known touchdowns. An average of close to one and one-half touchdowns a game, it continues to be a Marshall record.

Likewise, Jack’s 258 career points are still the most scored by a position player. Kicker Dewey Klein, with 330 in four seasons, is the only person ahead of him.

Still unaccounted for however are four touchdowns believed “lost” or overlooked in newspaper accounts. Missing, too, are precious reels of film showing Hunt in action. These were either “borrowed” by certain scholastic coaches, who claim otherwise, or were stolen by unscrupulous entrepreneurs. One suspect is a beer garden owner.

“People would ask Jack if they could borrow these things and he would, he’d trust them,” May Hunt said. “He was that kind of person. He trusted everybody.”

But here another anomaly occurs regarding Hunt’s all purpose yardage. As I wrote in The Herald-Dispatch in 1983: “In 1940 newspaper researchers were able to credit Jackie Hunt with 767 authenticated net rush yards in ONLY 30 carries! That’s more than 25 yards a tote! Now here’s the catch, 27 of these were the touchdown carries that set the record! ‘I sure as hell carried the ball more than 30 times that year,’ Hunt laughed.”

How many? We’ll never know. Educated guessers have placed his career rushing attempts in the 400 range, or between 150 to 175 a season, and his career rushing yardage in the 3,000- plus range, rather than his “official” 1,956. His career pass receptions and kickoff and punt returns probably added another 750 to 1,000 yards. Also impossible to trace are his passing and punting figures.

Nonetheless, a strong sense of his extraordinary versatility, unusual even in that one-platoon era, can be drawn from Marshall’s 31-19 loss to Wake Forest in Winston-Salem in 1940. Against the Demon Deacons that day Hunt rushed 18 times for 106 yards, completed one of three passes for five yards, caught five of Andy D’Antoni’s southpaw bullets for 65 yards, punted four times for an average 47 yards and scored two touchdowns, one a brilliant 52-yard run through the Deacon secondary. Quite a day’s work.

Earlier in the 1940 season against Virginia Tech in Fairfield Stadium, Hunt gained 51 yards in four consecutive carries to score the winning touchdown in a bruising 13-7 upset.

The previous year as a sophomore against Wake Forest, he rushed 10 times for 84 yards, scored one touchdown, kicked one extra point, punted an amazing 13 times for a spectacular 43 yard average, and returned one punt 19 yards. On defense, he doubled as a middle linebacker and cornerback but his tackles, assisted tackles, pass deflections and what not were uncounted.

In Marshall’s only victory over the Deacons in 1941, all that newspaper accounts give us about Hunt in this “major national upset” is the nine of nine passes he caught (actually eight of eight, one was disallowed by a penalty) from quarterback Jeeter Harrell. Three of these gained 38 yards in a bruising go-ahead touchdown drive in the third quarter. Playing halfback (cornerback) and linebacker on defense, he intercepted three passes, still a single-game Marshall record.

“See, the ‘Old Man’ (Henderson) tried to outsmart them,” Hunt told me years later. “He had me catching passes as an end when they were defensing me to run. Then, when they looked for me to catch the ball, I ran it. And ran it all over the park that day and I didn’t score a touchdown.”

His durability was remarkable even in an era when 60-minute players were common. Perhaps the best example of this is found in the torrid, 21-touchdown explosion he set off in Marshall’s last five games of 1 940 that broke Leach’s record. Hunt began it with four against Scranton, followed by four more against Morris Harvey, five against Detroit Tech, four versus Cincinnati Xavier and four against Wesleyan.

Obviously, there was more to Jackie Hunt as a total person than Jackie Hunt the All-American. The most accurate description of him says he lived the way he played – at a kind of affable, easygoing, rambling gait that he could instantly kick into high gear. In fact, when he entered Marshall his disposition was so low key that Henderson assigned halfback Lee “Boot” Elkins to give the rising young sophomore star pregame one-on-one pep talks. Boot would sit next to Hunt as game time approached and invent a string of insults their opponent purportedly had hurled against him, Huntington, Marshall and the state of West Virginia.

“It always worked!” I can still hear Boot chirp. “He never caught on.”

Henderson had other methods to rouse Hunt. He used one at halftime of the 1941 Wake Forest game that fueled the rumors that Hunt often went astray at night after practice.

“I couldn’t even jaywalk in this town without everybody knowing it,” he said in later years. “How could I go around bar hopping?”

True, he couldn’t. But when nosy fans milling around outside the Herd dressing room at the half of that fearsome battle saw Hunt stagger out last, doubled over and gasping, they nodded knowingly to each other. “Jackie’s got a hangover,” they said. What they didn’t know was that he’d taken a sucker punch to the solar plexus thrown by Henderson, of all people, to rouse his laconic star.

“The Old Man had gotten all steamed up about the first half,” Hunt recalled. “I think we were behind. Anyway, I just sat there not paying much attention. Hell, I’d heard that stuff before. No sense wasting your energy getting excited. When we all started to file out I got up last and was kind of walking slow out the door when the Old Man punched me. ‘Dammit, Hunt!’ he says to me. ‘Wake up!’ Hardest I was hit all day.”

Finally, there’s an odd, little-known twist to Jackie Hunt’s historic 27th touchdown. He almost didn’t get it. Late in the third quarter, Hunt, having already scored three times, passed up a chance to score a fourth and get the record. And the ball was on the 1-yard line. A gimme.

“I’d forgotten about the record,” he confessed. “So I told Andy to give the ball to somebody else.”

Infuriated by Hunt’s modesty, Henderson yanked both him and D’ Antoni. Jackie setting the touchdown record was the one statistic Henderson wanted publicized. So much so that early in the fourth quarter he relented and returned him to the game, this time as an end from where, on his first play, he scored from 48 yards out on a dazzling broken field run off an end-around play. Only then did it occur to Henderson that if he’d pulled Hunt to punish him at the start of the fourth quarter the rules would have prevented his reentry. Under limited substitutions reentries weren’t permitted in the same quarter.

• • •

“Oh, I have no regrets, I’m happy I went to Marshall,” Hunt said a few years before his death. He’d become a successful car salesman by then. “Times change. The game’s changed. I don’t know if I could even make the team today,” he said with a straight face.

“But sure, I guess I’ll always be curious about just how far I really carried that football.”

Amen. He probably does, now. RIP, Jack.

• • •

THE JACKIE HUNT FILE

Born February 17, 1920; Died June 21, 1991, Huntington, W.Va. Huntington High School Career:

1936 – West Virginia All-State halfback-defensive back, Huntington High School. Scored 15 touchdowns.

1937 – West Virginia All-State offensive back-defensive back, Huntington High School. Unanimous choice. Scored 17 touchdowns.

Marshall College Career:

1940 – Associated Press Little American, first team.

1940 – United Press All-American honorable mention.

1940 – Williamson System All-American, second team.

1940 – North College All Stars first team for annual North-South game. 1940-Grantland Rice All-American, special honorable mention as one of the 10 best backs in America.

1940 – National collegiate scoring champion. Scored 27 touchdowns to set a new NCAA record.

1941 – New York Sun All-American, first team, Marshall College.

1941 – Players All-American, honorable mention.

1941 – Drafted U.S. Army Air Force after scoring school-record 43 career touchdowns for Marshall.

1942 – Eastern Army-All Stars selection.

1942 – College All Star selection. Drew 263,527 votes in a nationwide poll conducted by “The Chicago Tribune.”

1945 – Drafted by the Chicago Bears as cornerback-punter-receiver. Placed on disabled list after suffering a late-season elbow injury.

1946-47 – Played in the American Football League for Paterson, N.J., before recurring arm injury forced his retirement.

1977 – Elected to the West Virginia Sports Writers Hall of Fame.

1984 – First person elected to the Marshall University Sports Hall of Fame.