The story of a river, a city, a war and a man named Huntington

By Joseph Platania

HQ 20 | WINTER 1995

Like a faded photograph, the glory days of Guyandotte are little more than fond memories of those who recall living there when it was a cluster of activity at the confluence of the Ohio and Guyandotte rivers.

In earlier days, about the time of the Civil War, Guyandotte welcomed the prosperity of businessmen and wealthy families, as well as presidents and statesmen, all traveling through the area by stagecoach or along the river. The locale served as a trading post and later as a significant river landing. Like other settlements in this area, it felt the devastation of the Civil War. Afterwards the town continued to host travelers, including a businessman named Collis P. Huntington. Unfortunately, the railroad magnate declined to build his new railroad in Guyandotte, instead opting to build in a cornfield just a few miles to the west.

But though Guyandotte has been engulfed by its “younger sister” Huntington, the sleepy little town’s rich heritage has not faded completely. Preservation societies and Civil War enthusiasts are working to make sure these memories are kept alive, reenacting Civil War history, restoring pieces of the town’s past and ensuring that its golden age is remembered by more than old photographs.

There are several versions of how the town received its name. One states that “Guyandotte” is a corruption of “Wyandot,” the name of a tribe of Native Americans who lived in the vicinity. Another story is that a French trader named Guion called the river “The Giondot” after himself and the Indian tribe. Local historian Tom Philip Smith wrote that Guyandotte was “George Washington’s spelling of the old Indian name Di-on-dotti, meaning growers of tobacco, of the generic tribe of the Hurons.” Whatever its origin, surveyors in 1775 decided to name the settlement “Guyandotte.”

Today, as you drive up Fifth Avenue toward Guyindotte, the East Huntington Bridge looms over the skyline and crosses the western border of the former settlement. Along the avenue, a gentle breeze slightly ruffles the leaves of a huge sycamore tree that towers over the old Methodist cemetery where stone markers identify the resting places of Revolutionary War soldiers and early settlers born in the 18th century. Many died during a cholera epidemic.

The Madie Carroll House, at 234 Guyan St., stands in the shadow of the East Huntington Bridge. Now empty and undergoing restoration, the house is a remnant of Guyandotte’s storied past. The Carroll House, the oldest in Cabell County, was floated down the Ohio River from Gallipolis, Ohio, in sections on a flatboat and reconstructed by James Gallagher in 1810.

Jim McClelland, director of the Greater Huntington Park and Recreation District which owns the Madie Carroll House, believes it “mirrors” the history of Huntington. He explains that members of some of Huntington’s “first families,” such as the Buffingtons and the Holderbys, owned the house before Thomas Carroll bought it in 1855.

The Civil War period, especially the Nov. 10, 1861, “Raid on Guyandotte,” affected the house, but it was spared by Union troops when Mary Carroll, Thomas’ wife, locked herself inside the house and refused to come out with her children.

After the Civil War, Madie Carroll’s mother – Thomas and Mary’s daughter-in-law-operated a boarding house for a while called the “Carroll Inn.” Men working on the river were frequent guests, and it is thought that stagecoaches arriving from Richmond, Va., on the Kanawha Turnpike, which came up Guyan Street, stopped at the house.

In addition, the house has witnessed many of the Ohio River floods that have occurred, especially the disastrous floods of 1884, 1913 and 1937.

Thomas Carroll’s son Michael was a carpenter and enlarged the original board-and-batten house, expanding the breezeway – which connected the large brick kitchen with the house – to add a dining room, music room and hall. Madie Carroll, Michael’s daughter who was a well-known piano teacher, lived in the house from her birth in 1886 until the early 1970s. She died in 1975. Several years later, her home was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Madie Carroll House is one of as many as 70 documented historic buildings and sites in Guyandotte. Many were built or existed before the Civil War. They include private residences, hotels, churches, a livery stable, jail, firehouse, bank and businesses such as a blacksmith, drug store and woolen mills.

In the 1935 Cabell County Annals and Families, noted local historian George S. Wallace states that Guyandotte is “one of the oldest towns on the Ohio River and the most historic village in the county.”

Historically, the importance and growth of Guyandotte have been dependent on its geographical position as a junction and transfer point on the Ohio River.

As far back as the 1600s, both the Delaware and Wyandot Indian tribes lived along the river banks with trails running from southwestern Virginia to the mouth of the Big Sandy River. According to one account, as late as 1850, Wyandots lived in a settlement a short distance from the town.

The first Europeans known to visit the area that became Guyandotte were Rene Robert La Salle, a French explorer, and his party of travelers who came down the Ohio River in late 1670. The first settlement consisted of a crude river landing and a few log cabins on the river bank.

In 1796, Thomas and Jonathan Buffington came to the mouth of the Guyandotte River to take possession of a part of the huge Savage Land Grant which had been purchased for them by their father. Thomas built his home on the east side of the Guyandotte at the mouth, while Jonathan built on the west side.

At the beginning of 1800, Thomas Buffington had, out of necessity, established a raft-type ferry service across the Ohio and one across the Guyandotte.

In 1804, Methodists established at Guyandotte one of their earliest congregations in the United States. The original church was built on Guyan Street, just west of where the old Methodist cemetery now is located, on land donated by Thomas Buffington.

A trading post was established around 1806, and Native Americans in the region bartered furs, fish, game and maize [corn] for calico, whiskey and plug tobacco.

According to Smith’s unpublished Book of Guyandotte, during the period 1805-1807, “8,000 bearskins were shipped from the Guyandotte area.”

The year after Cabell County was established the Virginia General Assembly, in 1810, created the town of Guyandotte by condemning 20 acres of property owned by Thomas Buffington. That year a young Irish riverman named James Gallagher purchased a lot in the new town and, after floating his house in sections down the Ohio River on a flatboat from Gallipolis, moved onto the lot. This structure later became the Carroll House. Other lots were sold at auction by town trustees with the money going to Buffington.

A map of the new town shows that it was laid out on a grid pattern with six streets: three running east and west and three running north and. south. Guyandotte soon developed into an important river landing from which farm products, particularly molasses and tobacco, as well as salt, timber and barrel staves were shipped down the Ohio to the Mississippi. The village also was the first seat of Cabell County.

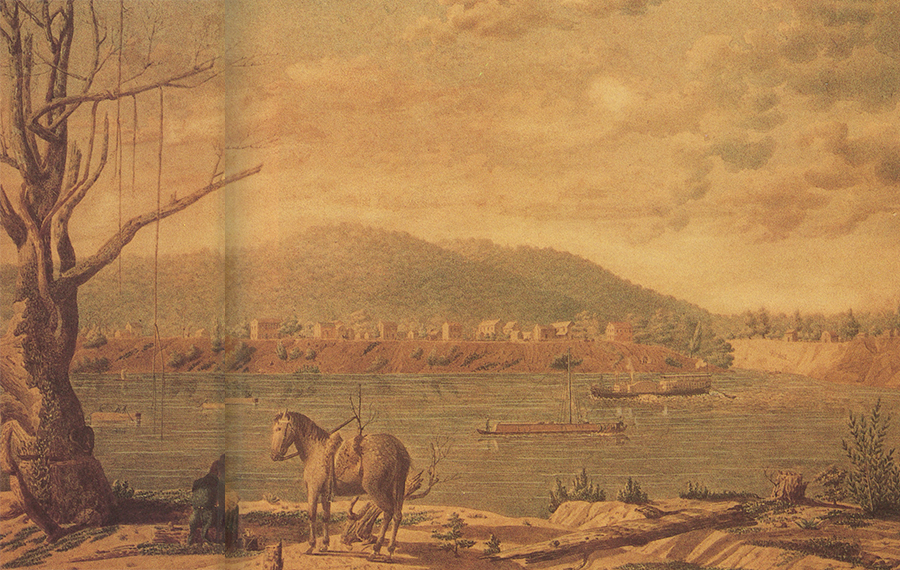

In 1823, a 20-year-old French artist named Felix Achille Beaupoil de SaintAulair, who was traveling on horseback through the new nation of the United States, dismounted on the river bank in Ohio opposite Guyandotte to make a drawing of the village and the river. The scene he later painted, which includes the artist and his horse, now hangs in the Huntington Museum of Art. The pastel painting, titled “The Big Guyandotte,” shows the village with about 20 buildings, mostly residences, although some appear to be business establishments.

By the mid-1820s, hundreds of steamboats were carrying freight and passengers on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. This burgeoning traffic did not affect the slow pace of life in most small river towns. Guyandotte, however, was a notable exception. The village was strategically located to take advantage of the growing importance of Cincinnati, Ohio, as a commercial center and gateway to the South.

The quickest mode of travel to Cincinnati from Washington, D.C., and Richmond, Va., was by stagecoach over the James River and Kanawha Turnpike and then by steamer from Guyandotte. By 1831, stagecoaches were making daily trips between Lewisburg, W.Va., and Guyandotte. Small hotels or inns were built to accommodate travelers who wished to rest before continuing their journey. This not only brought in tourist dollars but also ended the isolation so characteristic of small towns with little contact to the rest of the world.

In the public rooms of the hotels, local citizens had the opportunity to discuss national and world events with well-informed businessmen, politicians, government officials and travelers from Europe. According to one account, the stage from Richmond made steamboat connections at the Guyandotte landing for such important travelers as Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay.

Wallace writes that “measured by antebellum standards, there was much wealth [in Guyandotte]. It was a place of comfortable homes and conservative people and it gave to the business and political life of the county many outstanding men.”

He also writes that in 1835 the little town contained “40 dwellings, five store houses, one house of public worship free to all denominations, one primary school, a steam grist mill, sawmill and carding machine, one saddler, two cabinet makers and a number of other mechanics.” Guyandotte’s population in 1835 was estimated at 300.

In 1849, a suspension bridge was built over the Guyandotte River on what now is Third Avenue. Several years later, locks and dams were built upriver, an area which became the scene of a thriving timber industry. Logs were floated downstream to Guyandotte where the lumber was manufactured. The present bridge was built on the site of the old suspension bridge which stood until 1907.

A harbinger of future conflict occurred in 1844 when, nationally, the Methodist Church split over the issue of slavery. At that time, the Guyandotte congregation built a new church at its present site on Main Street. The church building later was used as a Confederate supply depot until it was burned by Union soldiers. The present frame church was built on the original foundation in 1869-70.

The outbreak of the Civil War would take a heavy toll on Guyandotte and its residents whose allegiances were sharply divided.

On Dec. 10, 1860, a company of Confederate soldiers was organized in Guyandotte for the purpose of protecting the Virginia flag which had been raised on a flagpole on the riverbank. On April 20, 1861, the Border Rangers were organized by Albert Gallatin Jenkins, who became their captain. They later became part of the 8th Virginia Cavalry, CSA.

Until late 1861, the people in Virginia’s counties west of the mountains were divided by what state government to recognize.

In September 1861, a regiment of Union troops was recruited to garrison Guyandotte against the Confederates. On Oct. 22, a federal recruiting camp was established in the town. Federal soldiers stationed in Guyandotte were under the command of Col. K.W. Whaley. On Nov.10, 1861, townspeople believed that the presence of Union troops meant safety and that the nearest rebels were 80 miles away. However, that night Col. Whaley’s garrison of 180 men was suddenly raided by some 800 Rangers commanded by Vol. Col. John B. Clarkson and Capt. Jenkins.

On that fateful Sunday night, the Confederates engaged in a skirmish with Union troops in Guyandotte near and on the suspension bridge. The attack came as such a surprise that some of the Union soldiers were caught away from their rifles. One of the Border Rangers later recalled, “We captured all we could find of the Yanks, their arms and commissary stores, put out pickets and stayed all night and left the town the next morning with 110 prisoners for Dixie.” They also left 13 dead and many wounded.

On the following day, in retaliation for the raid, several companies of the 5th W.Va. Infantry Volunteers (federal), commanded by Capt. John L. Ziegler and aided by forces of the Ohio State Militia from Proctorville, Ohio, attacked Guyandotte. One account states that the Union forces arrived on a “side wheeled steamboat” from Ceredo, where they were stationed. The federal soldiers burned as much as twothirds of the town, including much of the business district.

Doris Miller in her Centennial History of Huntington 1871-1971 reports that in a 1901 affidavit, Joshua “Doc” Suitor, an old-time Guyandotte resident, stated the town was in general confusion with streets in the business portion filled with merchandise from store houses; it was generally thought that the Confederates would return to seize the goods.

In Miller’s opinion, it was a blow which affected both Northern and Southern sympathizers, “and one from which Guyandotte never quite recovered.”

For the remainder of the war, Cabell County was “Southern in sympathy but Union in control,” according to a 1959 county history.

In 1863, the county seat – which had been in Barboursville since 1814 – was moved back to its original site in Guyandotte until it was returned to Barboursville in 1867.

William Holderby, an Englishman from Yorktown, Va., had arrived in Cabell County prior to the Buffingtons. He occupied the field where Guyandotte now stands and operated a brick hotel near where the Guyandotte and Ohio rivers meet (near the present floodwall).

The Holderby Hotel later was operated by Gen. JohnS mith, A.W. Whitney and others. Passengers traveling by stage and boat were entertained in this well kept hotel, which burned during the Civil War. According to one account, the Confederate flag flew in front of the hotel continuously during the war.

Other Guyandotte residences and businesses were pressed into wartime service. The McGinnis Home, at 101 Main St., was headquarters for Jenkins, who had become a general. The Crawley House at 307 Water St., then the Jacob Hiltbrunner Hotel, was used as a Union hospital where, according to a historical survey, Gen. McClelland “recuperated from wounds and gave his sword to a local resident.”

The end of the war meant that Guyandotte could return to prominence as a commercial center. Coal mines were opened nearby and fleets of barges and other riverboats carried coal, lumber and farm products from the town downriver to Cincinnati. Guyandotte also became a bustling sawmill town where logs and crossties were sorted and floated downriver to market. “Stores, taverns and saloons became crowded again,” a local history states.

Four years after the war, two horsemen rode into Guyandotte – Collis P. Huntington, a nationally-known financier and builder of the Central Pacific Railroad, and Col. D.W. Emmons, Huntington’s brother-in-law and business associate.

During 1869-70, Guyandotte, as well as other villages and landings along this part of the Ohio River, were under consideration as the western terminus of Collis P. Huntington’s new Chesapeake and Ohio Railway.

There are many stories as to why Huntington decided not to locate the railhead for the C&O in Guyandotte.

“On one occasion,” the Huntington Herald-Dispatch of Nov. 2, 1930 reported, “the magnate was fined in the [Guyandotte] mayor’s court because his horse, tied in the street, swung about to take a position on the sidewalk. The incident of the fine led Mr. Huntington to the decision to build a new city to the west of the Guyandotte River, one which was destined to absorb and engulf its so much older sister.”

Another story claims that as Huntington entered a store at the corner of Bridge and Main streets, the owner demanded, “Is that your horse? I don’t allow anyone to hitch a horse to my tree. Go and unhitch him!” To this outburst Mr. Huntington replied, “I will, but I’ll hitch my railroad to that cornfield down the river.”

Whatever his reason, C.P. Huntington was dissatisfied with Guyandotte as the terminus for his railroad and began looking for a location where he could build his city. He selected a site along the Ohio River several miles west of the west bank of the Guyandotte. This generated protest from townspeople, but by February 1871 the new city was chartered by the State of West Virginia and named for the railroader. During the next few decades, many Guyandotte residents moved to Huntington and contributed to the new city’s growth and development.

Still, Guyandotte continued to demonstrate the hustle and bustle not usually associated with a river town.

Smith, a Guyandotte native, writes that “Guyandotte refused to go along with progress when the railroads came, and for 40 years devoted itself entirely to the Business of Living; having such a pleasant time of it that any interruption from the outside was unwelcome. In Guyandotte, time stood still from 1870 to 1910.”

By 1890 Guyandotte was linked to downtown Huntington, more than two miles away, by a new electric streetcar line with iron rails going up wide Third Avenue. This development set the stage for a future event: in 1911, Guyandotte was annexed as part of Huntington in its first expansion as a city.

George Wallace recounts one of the most exciting events that took place in the small town during the early 20th century – the robbery of the Bank of Guyandotte just before noon on Nov. 14, 1925. Thieves took $7,600 and bank personnel were locked inside a safe for a time until help arrived. One bank employee, who Wallace says was rather fat, almost became stuck in the safe. The thieves were later apprehended and brought to trial.

During the Depression the Bank of Guyandotte went under, never to rise again.

Guyandotte has a historic legacy in what now is the oldest section of Huntington. Surviving structures in the town, such as the Madie Carroll House, provide tangible evidence of its rich and varied past.

In the summer of 1990, the Madie Carroll House Preservation Society, Inc., under the direction of board members Elmer and Jacqui Van Kuren, received permission from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Floodwall Board and the City of Huntington to paint murals on the floodwalls, especially those surrounding the community of Guyandotte. The Van Kurens contacted local artists willing to volunteer their time and talent to the project. So far five sets of murals have been completed.

Guyandotte is not all historic landmarks and restored quaint houses – the community can boast of a modern post office as well as a branch of the Cabell County Public Library. There also are a dozen businesses in operation in the area and four or five churches conduct regular services.

Each November on the anniversary of the famous 1861 raid, the Guyandotte Civil War Days and Raid on Guyandotte, Inc., sponsors a monthlong event and educational experience providing nationally-known speakers and Civil War reenactments.

During the spring of 1993, the Madie Carroll House Preservation Society, Inc., collected more than $1,000 in pledges from members, a $5,000 matching grant from the Huntington Foundation, $7,000 from the State of West Virginia and a $20,000 federal HUD grant through the City of Huntington. Although the funds that have been awarded or pledged will not complete restoration on the historic house, they will complete the work necessary to open it to the public.

According to a preservation society newsletter, the Carroll House will be used as a museum, opened for meetings or used in cooperation with Ceredo’s Z.D. Ramsdell House for Civil War reenactments.

Plans also are in the works for a Civil War museum at the Guyandotte library, 203 Richmond St., exhibiting local resident Rick Whisman’s growing collection of literature, artifacts and reproductions.

With restoration and preservation work in progress on homes and other structures, and the annual historical events, more people are taking pride in Guyandotte, a child of the 19th century, and looking at what it may have to offer Tri-State residents for the 21st century.